This is a course notes (with a few extensions from other sources and the original course notebook) for reviewing based on the distributed system course videos by Martin Kleppmann. The source videos can be found here.

Introduction

Computer Networking

Latency and bandwith

- Latency: time until message arrives

- In the same building/datacenter: 10ms

- One continent to another: 100ms

- Hard drives in a van: 1 day

- Bandwidth: data volume per unit time

- 3G celluar data: 1Mbit/s

- Home broadband: 10Mbit/s

- Hard drives in a van: 50TB/box - 1Gbit/s

Client-server example: the web

When we talk about messages in distributed systems, we are not talking about one network packet, since a message maybe bigger than a single network packet, so the message has to be broken down into several network packets.

Don’t care too much about the details.

RPC

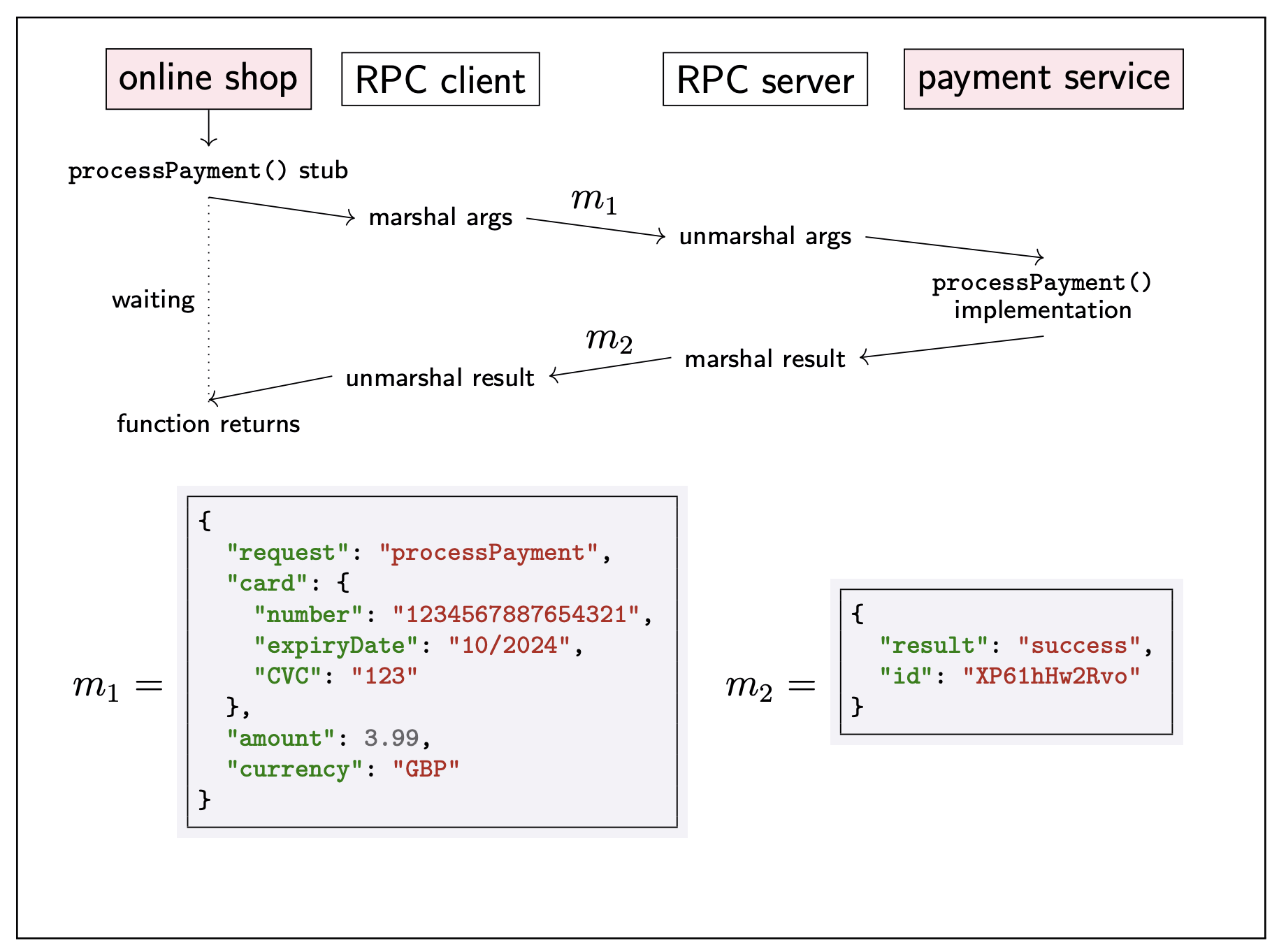

Ideally, RPC makes a call to a remote function look the same as a local function call.

- Location transparency: system hides where a resource is located. (But calling method remotely will have many errors which we will never encounter in the local environment…)

gRPC(Google, 2015), REST(often with JSON), Ajax in web browers

RPC in enterprise systems

“Service-oriented architecture” (SOA) / “microservices”

splitting a large software application into multiple services (on multiple nodes) that communicate via RPC

DIfferent services implemented in different languages:

So we need:

- Interoperability: datatype conversions (between different datacenters)

- Interface Definition Language (IDL) – language-independent API specification

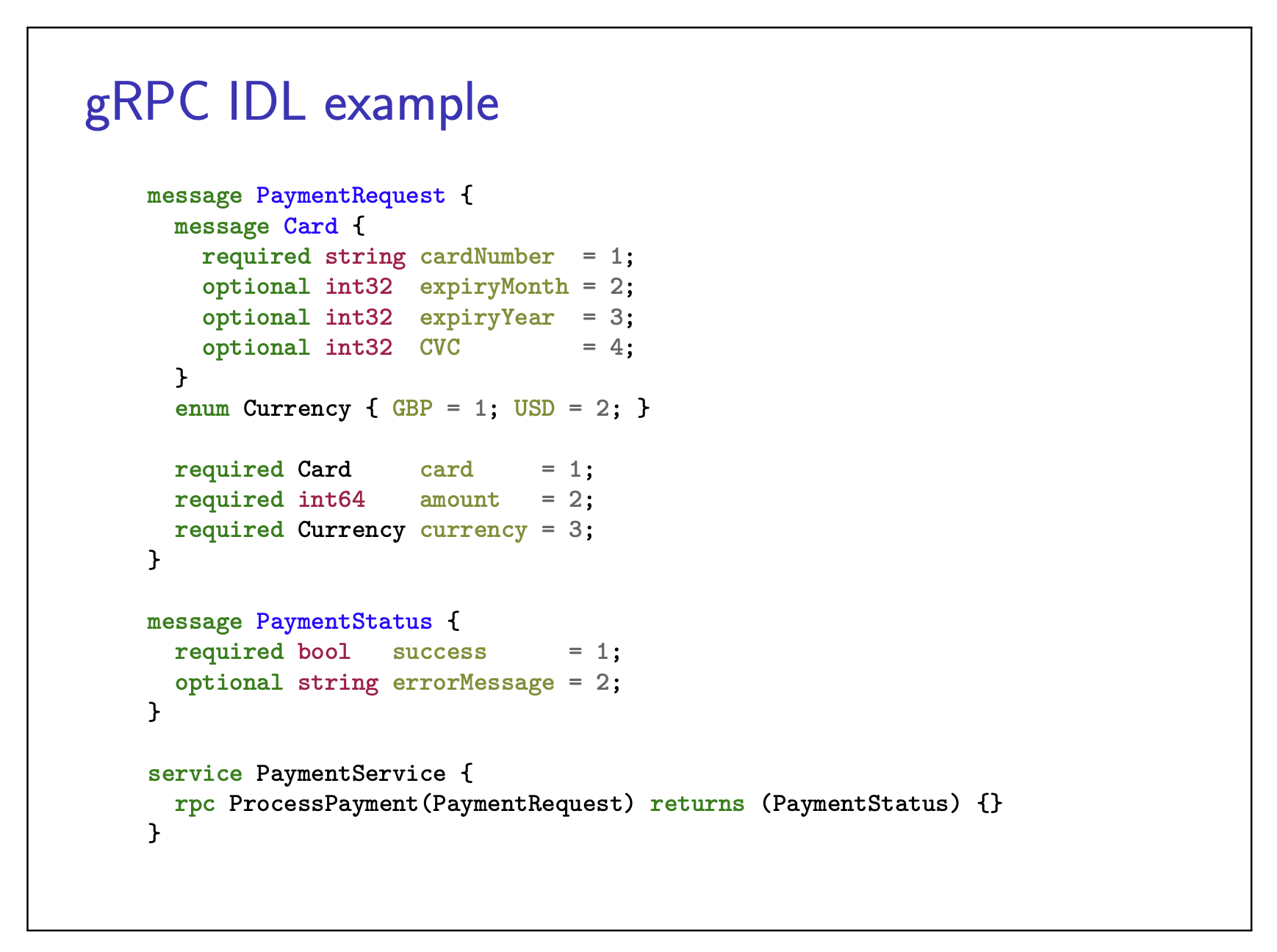

gRPC IDL example

Protobuf:

take this IDL and generate code in all of your favorite languages, which makes it easy to generate stubs in both the rpc client and rpc server

Models of distributed system

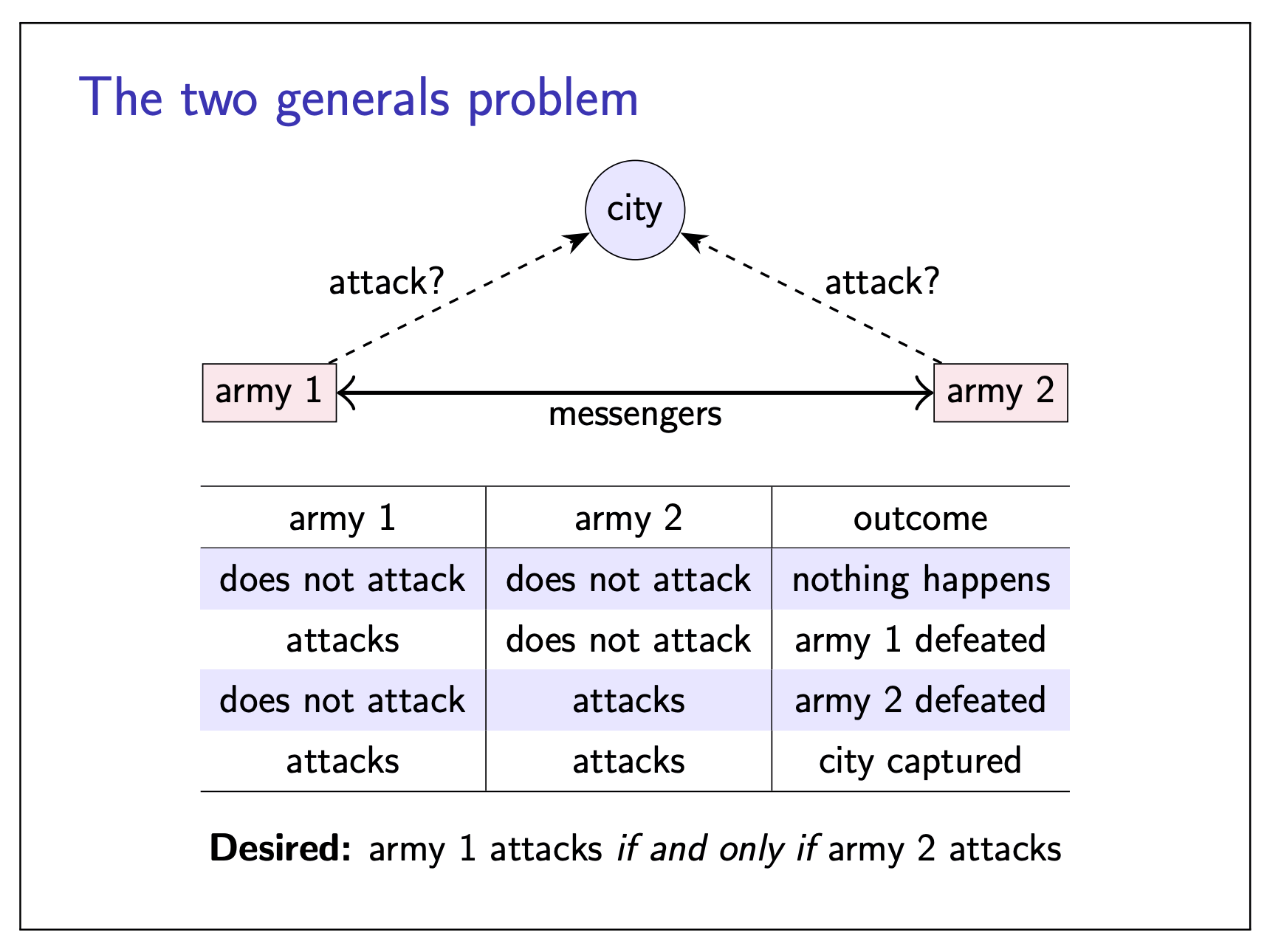

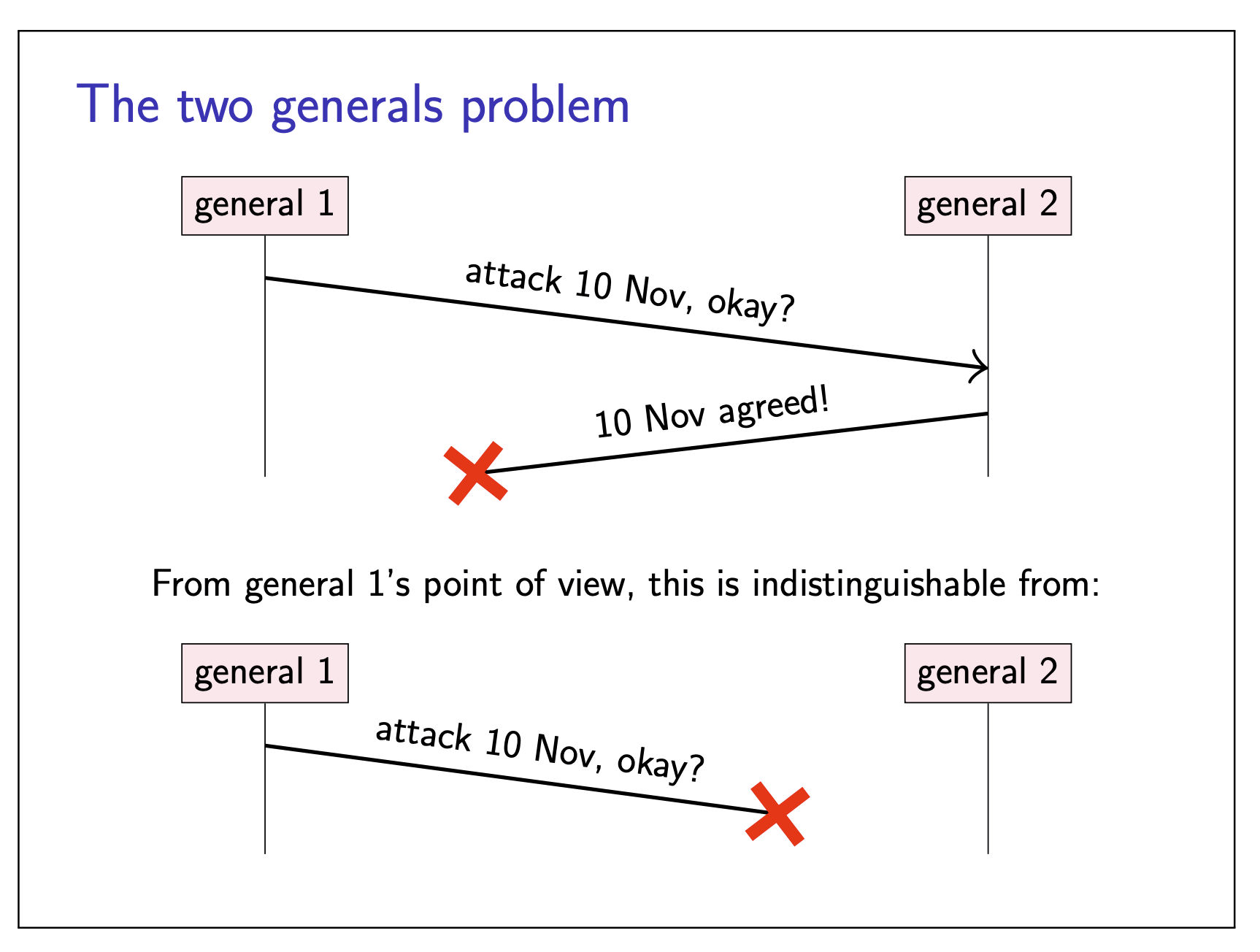

Two general problems

|  |

The problem is that no matter how many messages are exchanged, neither general can ever be certain that the other army will also turn up at the same time. A repeated sequence of back-and-forth acknowledgements can build up gradually increasing confidence that the generals are in agreement, but it can be proved that they cannot reach certainty by exchanging any finite number of messages.

No common knowledge: the only way of knowing something is to communicate it.

The two generals problem illustrate the issue of uncertainty in distributed systems, when we are not sure the message got through or not.

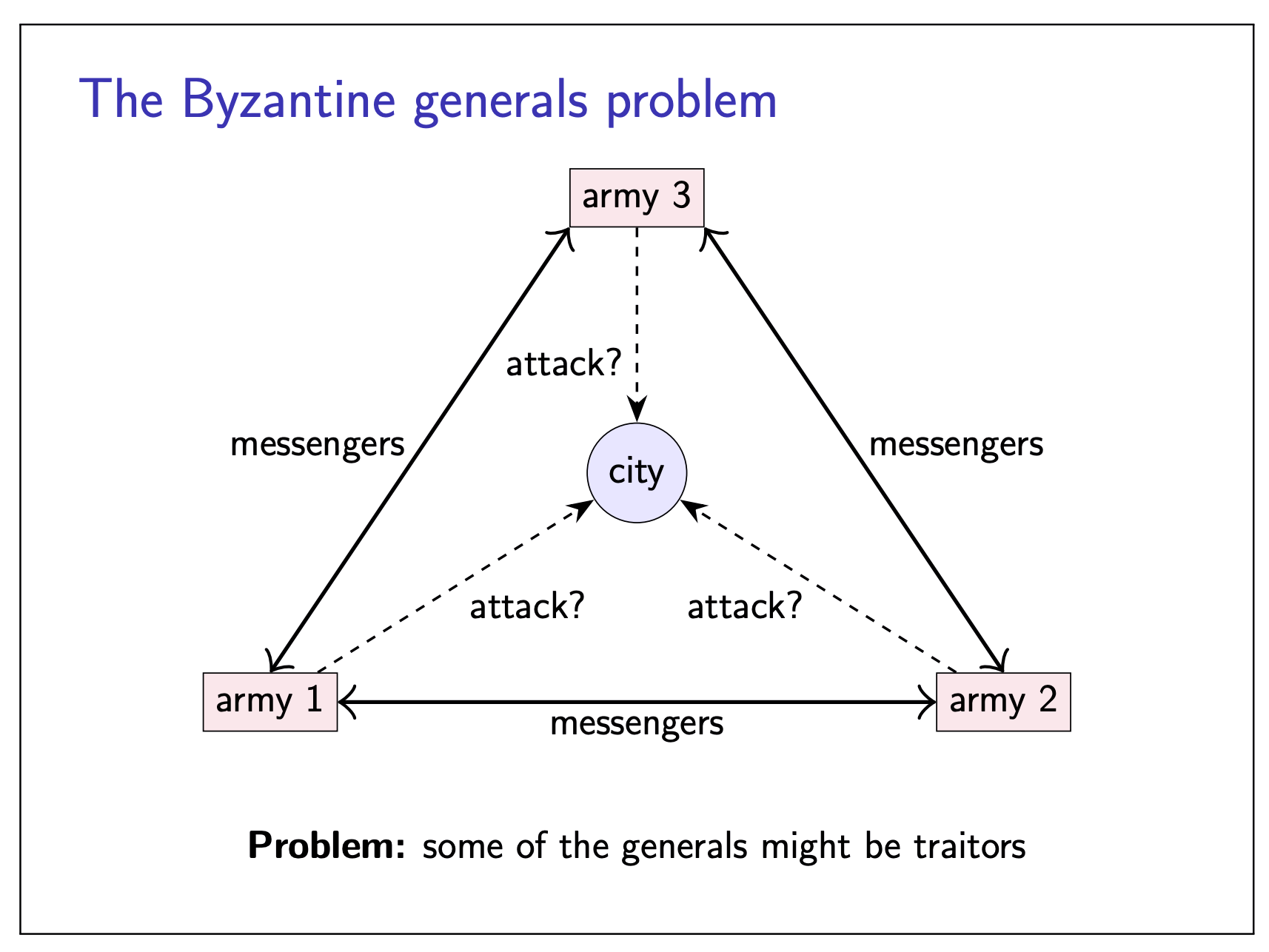

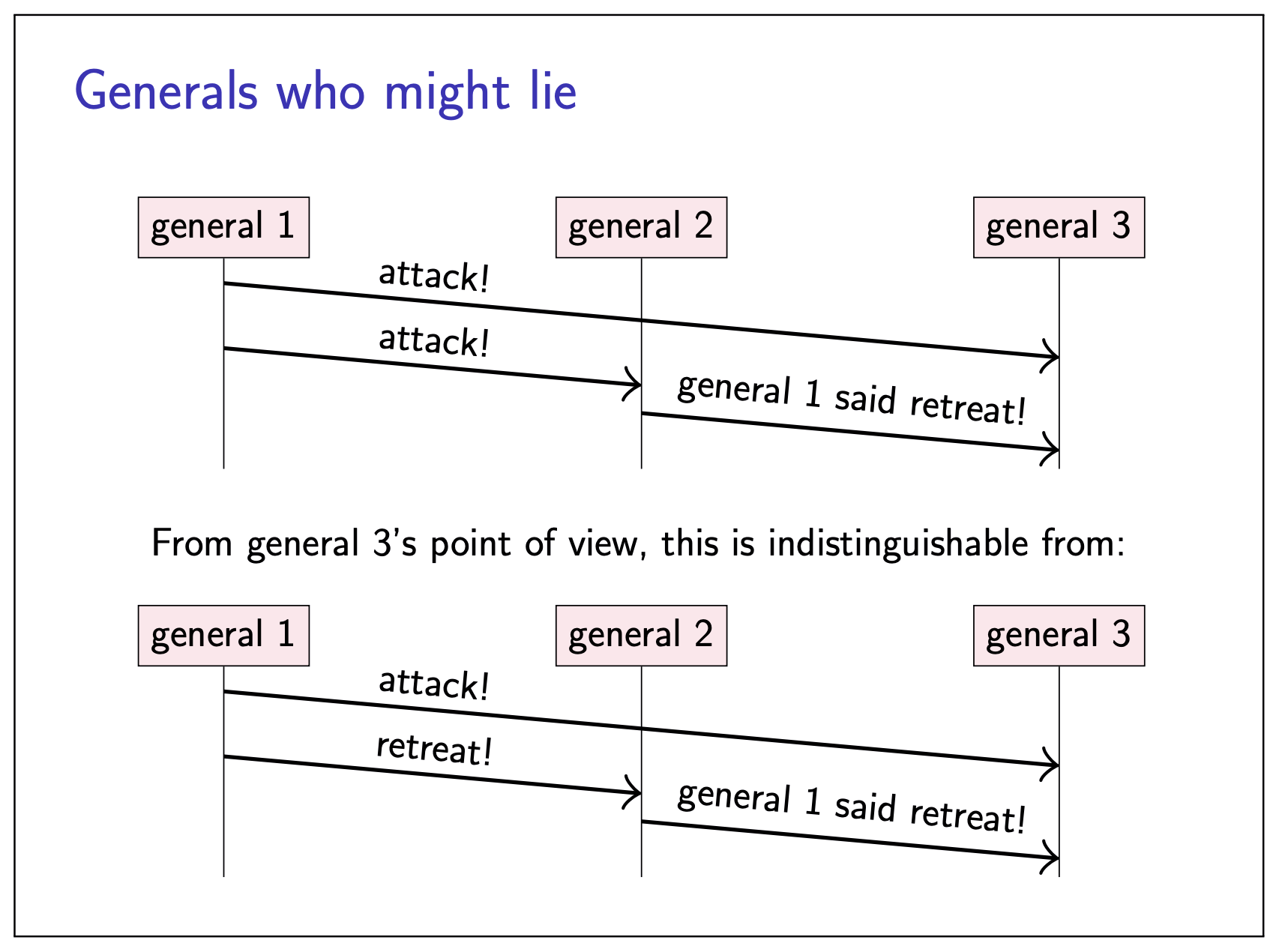

The Byzantine generals problems

To simplify the problem, this time we assume the message will be delivered correctly once it is being sent.

|  |

- Up to

- Honest generals do not know who the malicous ones are

- The malicous generals may collude

- Goal: honest generals must agress on plan

Two possible solutions:

- Theorem: need

- Cryptography (digital signatures): helps - but problem remains hard

System models

- Two general problem: a model of networks

- Byzantine generals problem: a model of node behavior

Capture assumpitions in a system model consisting of:

- Network behavior (e.g. message loss)

- Node behavior (e.g. crashes)

- Timing behavor (e.g. latency)

Choice of models for each of these parts.

Network behavior

Assume bidirectional P2P communication between two nodes, with one of:

Reliable (perfect links):

A message is received if and only if it is sent.

Messages may be reordered.

Fair-loss links: (by

retry(send) +dedup(receive) can turn into a reliable link)Messages may be lost, duplicated, or reordered.

If you keep trying, a message eventually get through.

Arbitrary links (active adversary): (by using cryptographic protocol such as

TLS, can turn into a fair-loss link unless the adversary decides to block all communications)A malicous adversary may interface with messages

(eavesdrop, modify, drop, spoof, replay)

Network partition: some links dropping/delaying all messages fr extended period of time.

Node behavior

Each node executes a specified algorithm, assuming one of the following:

Crash-stop (fail-stop)

A node is faulty if it crashes (at any moment).

After crashing, it stops executing forever.

Crash-recovery (fail-recovery)

A node may crash at any moment, losing its in-memory state.

It may resume executing sometime later.

Byzantine (fail-arbitrary)

A node is faulty if it deviates from the algorithm.

Faulty nodes may do anything, including crashing or malicous behavior.

A node is not faulty is called correct.

synchrony (timing) assumptions

Assume one of the following for network and nodes:

Synchronous:

Message latency no greater than a upper bound.

Nodes execute algorithm at a known speed.

Partially synchronous:

The system is asynchronous for some finite (but unknown) periods of time, synchronous otherwise.

Asynchronous:

Messages can be delayed arbitrarilly.

Nodes can pause execution arbitrarilly.

No timing guarantees at all.

Violations of synchrony in practice

Networks usually have quite predictable latency, which can occcasionally increase:

- Message loss requiring retry

- Congestion/contention causing queueing

- Network/route reconfiguration

Nodes usually execute at a predictable speed, with occasional pauses:

- Operating system scheduling issues, e.g. priority inversion

- Stop-the-world garbage collection pauses

- Page faults, wap, thrashing

Real-time operating systems (RTOS) provide scheduling guarantees, but most distributed systems do not use RTOS.

System models summary

- Network: reliable, fair-loss, arbitrary

- Nodes: crash-stop, crash-recovery, Byzantine

- Timing: synchronous, partially synchronous, asynchronous

This is the basis for any distributed algorithm. If your assumption goes wrong, all bets off.

Fault tolerance

Servive-Level Objective (SLO):

e.g. “99.9% of requests in a day get a response in 200 ms”

Service-Level Agreement (SLA)

contract specifying some SLO, penalties for violation

Achieving high availability: fault tolerance

Failure: system as a while isn’t working

Fault: some part of the system isn’t working

- Node fault: crash (crash-stop/crash-recovery), deviating from algorithm(Byzantine)

- Network fault: dropping or siginificantly delaying messages

Fault tolerance:

system as a whole continues working, despite faults (some maximum number of faults assumed)

Single point of failure (SPOF):

Node/network link whose fault leads to failure

We want to design a system without SPOF.

Failure detectors

Failure detector:

algorithm that detects whether another node is faulty

Perfect failure detector:

labels a node as faulty if and only if it has crashed

Typical implementation:

for crash-stop/crash-recovery: send message, wait response, label node as crashed if no reply within some timeout

Problem:

cannot tell the difference between crashed node, temporarily unresponsive node, lost message, and delayed message.

Failure detection in partially synchronous systems

Perfect timeout-based failure detector exists only in a sunchrnous crash-stop system with reliabel links.

Eventually perfect failure detector:

- May temporarily label a node as crashed, even though it is correct

- May temporarily label a node as correct, even though it is crashed

- But eventually, labels a node as crashed if and only if it has crashed

Reflects fact that detection is not instantaneous, and we may have spurious timeouts.

Time, clocks, and ordering of events

Physical time

Distributed system often need to measure time, e.g.:

We distinguish two types of clock:

- Physical clocks: count numbers of seconds elapsed

- logical clocks: count events, e.g. messages sent

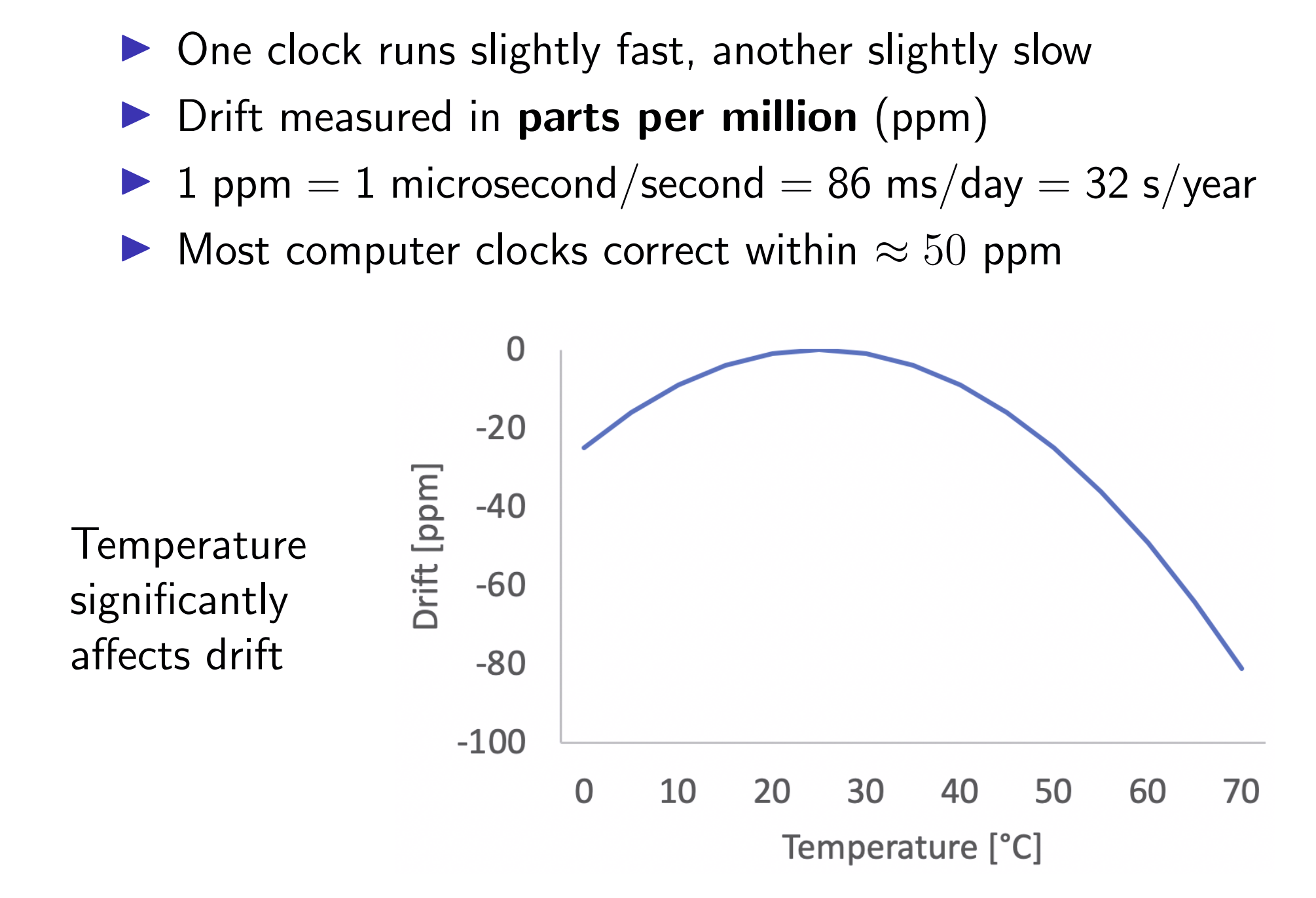

Quartz clocks:

Atomic clocks:

UTC

The difference between UTC and TAI is that UTC includes leap seconds, which are added as needed to keep UTC roughly in sync with the rotation of the Earth.

leap seconds

Due to leap seconds, it is not true that an hour always as 3600 seconds, and a day always has 86,400 seconds. In the UTC timescale, a day can be 86,399 seconds, 86,400 seconds, or 86,401 seconds long due to a leap second. This complicates software that needs to work with dates and times.

How computers represent timestamps

The most common approach in software is to simply ignore leap seconds, pretend that they don’t exist, and hope that the problem somehow goes away. This approach is taken by Unix timestamps, and by the POSIX standard. For software that only needs coarse-grained timings (e.g. rounded to the nearest day), this is fine, since the difference of a few seconds is not significant. However, operating systems and distributed systems often do rely on high-resolution timestamps for accurate measurements of time, where a difference of one second is very noticeable. In such settings, ignoring leap seconds can be dangerous.

Today, some software handles leap seconds explicitly, while other programs continue to ignore them. A pragmatic solution that is widely used today is that when a positive leap second occurs, rather than inserting it between 23:59:59 and 00:00:00, the extra second is spread out over several hours before and after that time by deliberately slowing down the clocks during that time (or speeding up in the case of a negative leap second). This approach is called smearing the leap second, and it is not without problems. However, it is a pragmatic alternative to making all software aware of and robust to leap seconds, which may well be infeasible.

Clock synchronisation

Computers track physical time/UTC with a quartz clock (with battery, continues running when power is off).

Dut to clock drift, clock error gradually increases.

Clock skew: difference between two clocks at a point in time.

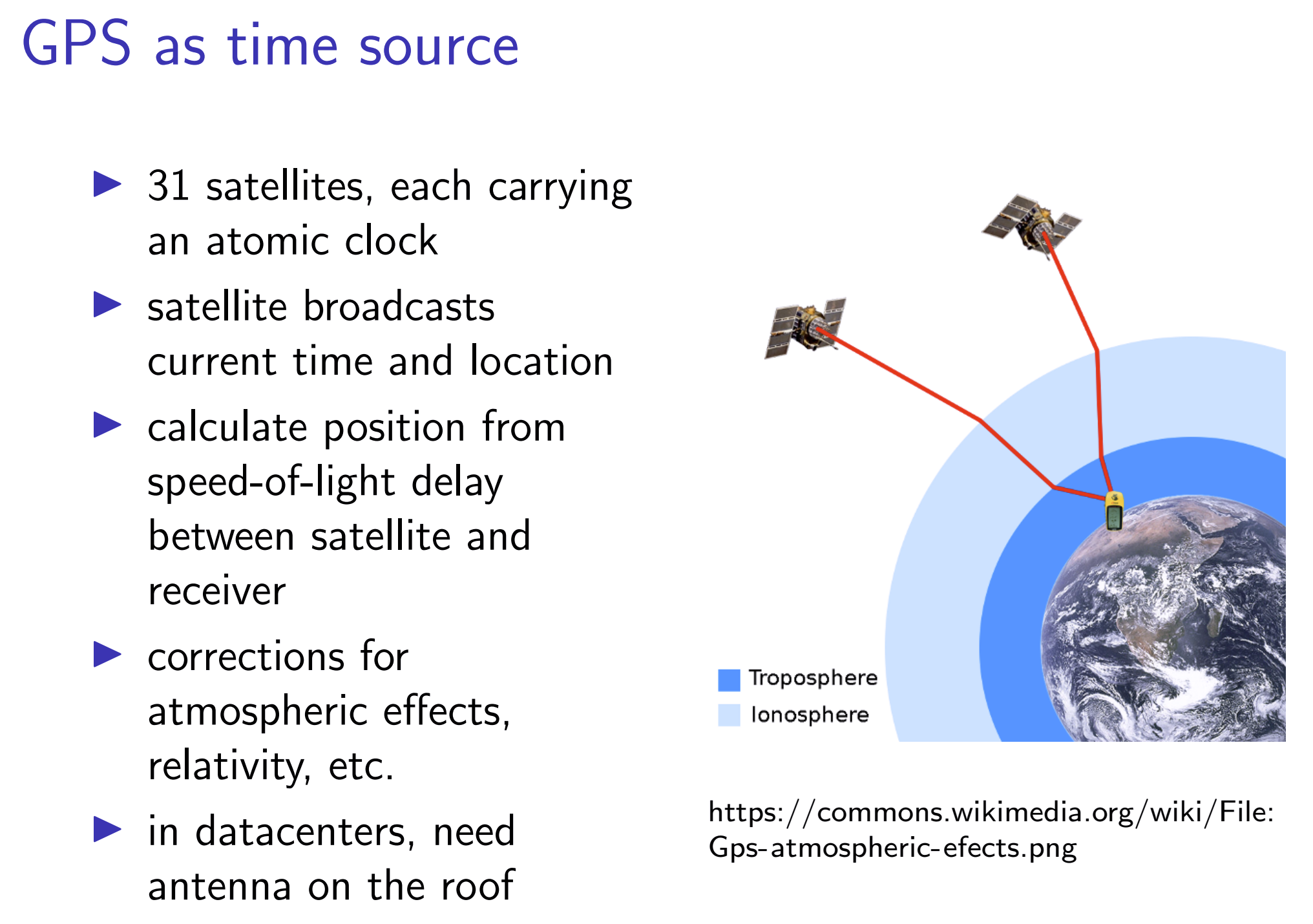

Solution: Periodally get the current time from a server that ha a more accurate time source (atomic clock or GPS receiver).

- Protocols: Network Time Protocol (NTP)

- Precision Time Protocol (PTP)

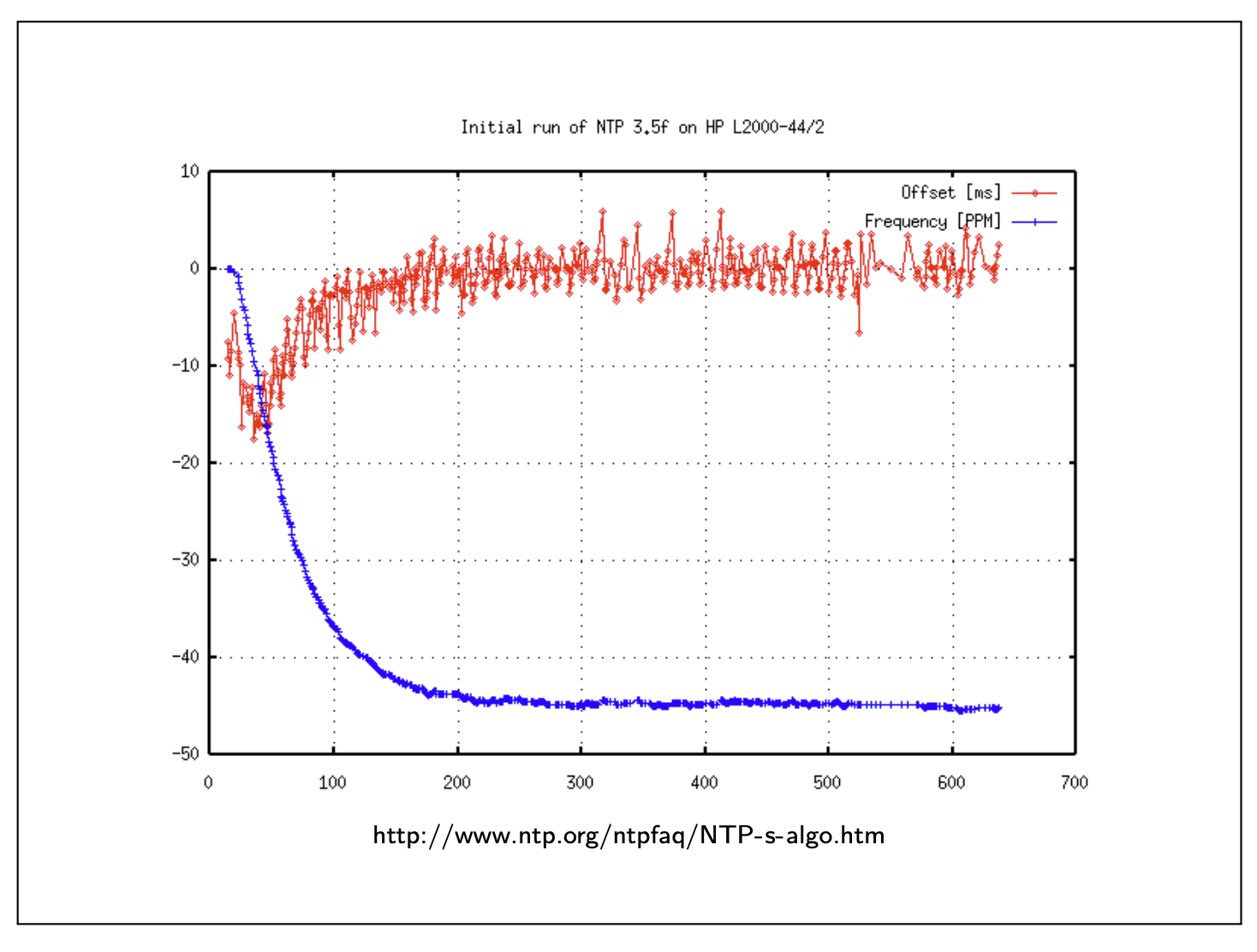

Network Time Protocol (NTP)

Many operating system vendors run NTP servers, configure OS to use them by default.

Hierarchy of clock servers arranged into strata:

The NTP Stratum model is a representation of the hierarchy of time servers in an NTP network, where the Stratum level (0-15) indicates the device’s distance to the reference clock.

Stratum 0 means a device is directly connected to e.g., a GPS antenna, atomic clock. Stratum 0 devices cannot distribute time over a network directly, though, hence they must be linked to a Stratum 1 time server that will distribute time to Stratum 2 servers or clients, and so on. The higher the Stratum number, the more the timing accuracy and stability degrades.

One server may contact multiple servers to discard outliers, or it can make multiple requests to the same server, and use statistics to reduce error due to variations in network latency.

By using these methods, clock skew can be reduced to a few milliseconds, in good entwork conditions, but can be much worse.

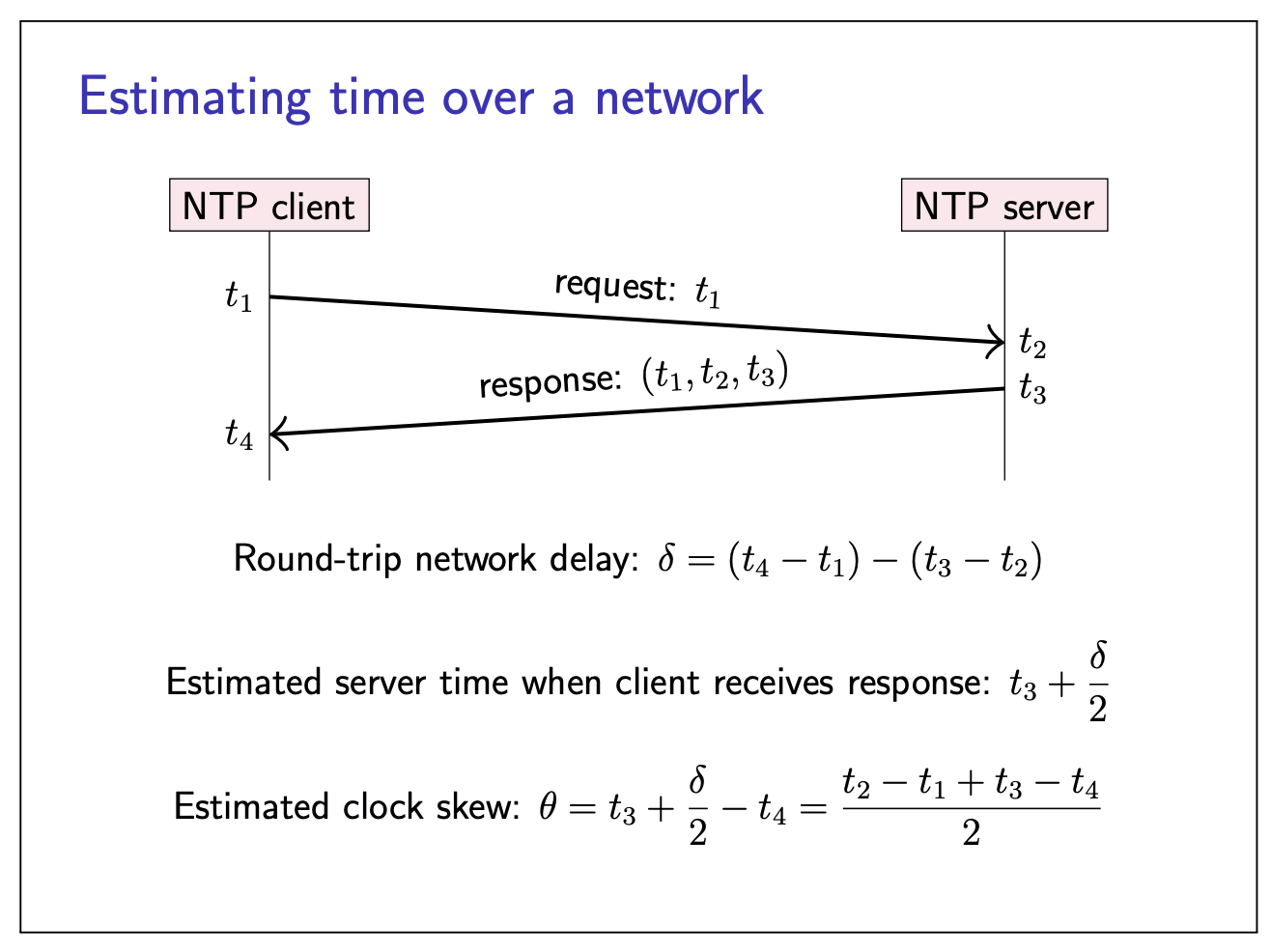

Estimating time over a network

Assume the sent time equals to the receiving time.

Correcting clock skew

Once the client has estimated the clock skew

If

slightly spped it up or slow it down by up to 500 ppm (brings clocks in sync within about 5 minutes)

If

suddently reset client clock to estimated server timestamp

If

(leavev the problem for a human operator to resolve)

System that rely on clock sync need to monitor clock skew!

Monotonic and time-of-day clocks

// BAD:

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

doSomething();

long endTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

long elapsedMillis = endTime - startTime;

// elapsedMillis may be negative!

NTP client steps the clock during this

// GOOD:

long startTime = System.nanoTime();

doSomething();

long endTime = System.nanoTime();

long elapsedNanos = endTime - startTime;

// elapsedNanos is always >= 0

NanoTime is a monotonic clock, never stepping, but slewing will also affect this clock.

TIme-of-day clock:

- Time since a fixed data (e.g. 1 Jal 1970 epoch)

- May suddenly move forwards or backwards (NTP stepping), subject to leap second adjustments

- Timestampes can be compared across nodes (if synced)

- Java: System.currentTimeMillis()

- Linux: clock_gettime(CLOCK_REALTIME)

Monotonic clock:

- Time since arbitrary point (e.g. when machine booted up)

- Always moves forwards at a near-constant rate

- Good for measuring elapsed time on a single node

- Java: System.nanoTime()

- Linux: clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC)

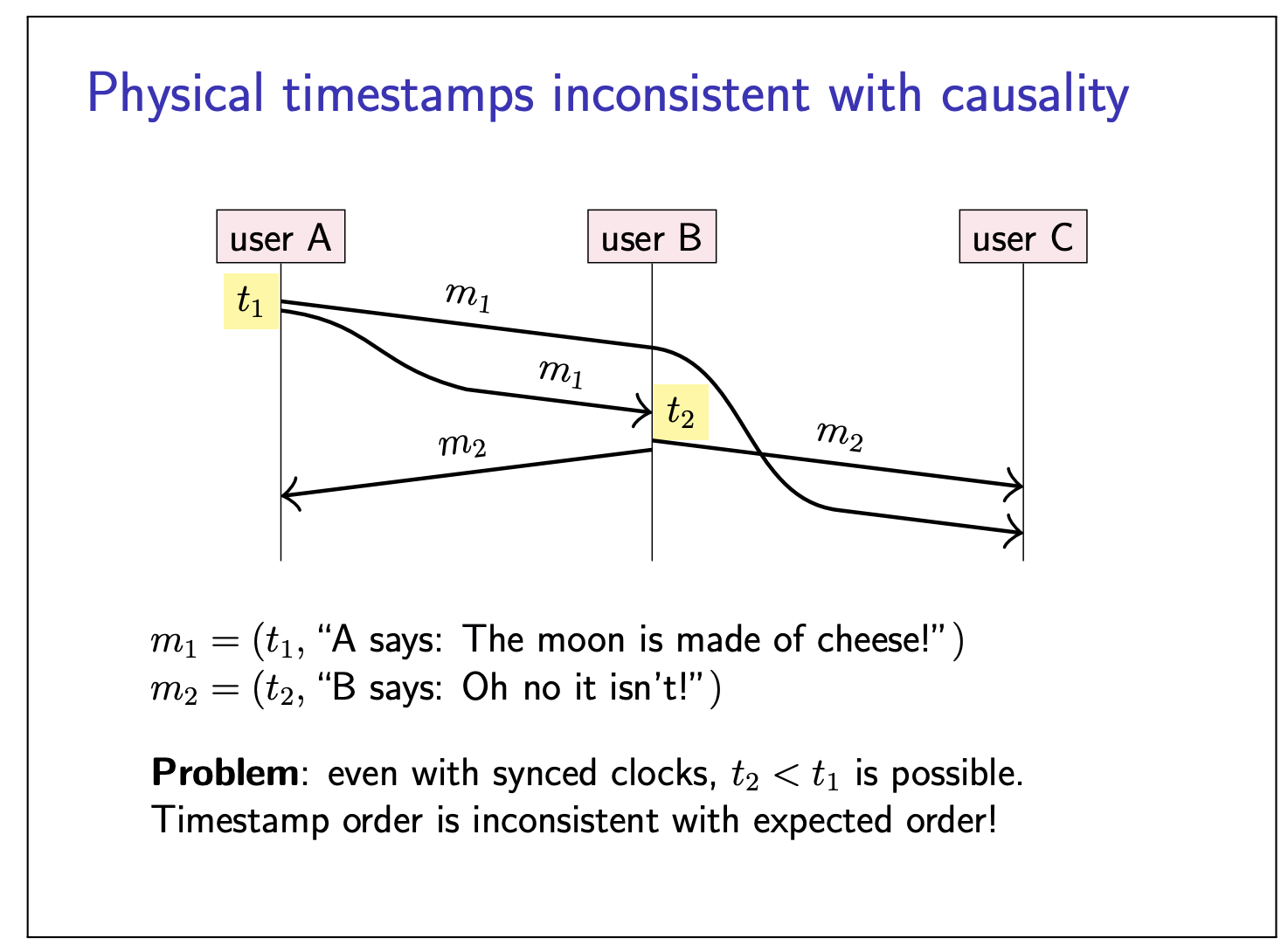

Causality and happens-before

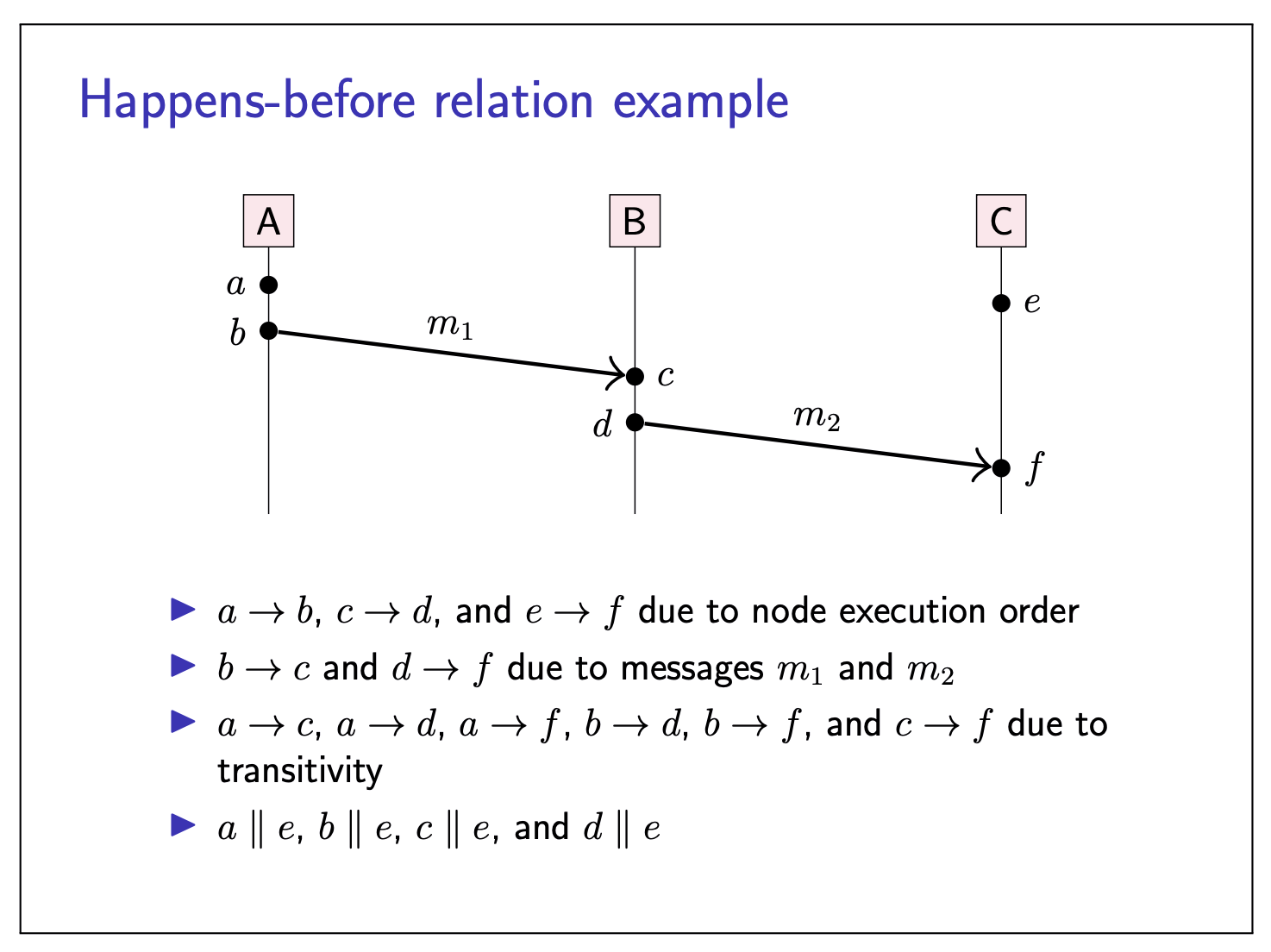

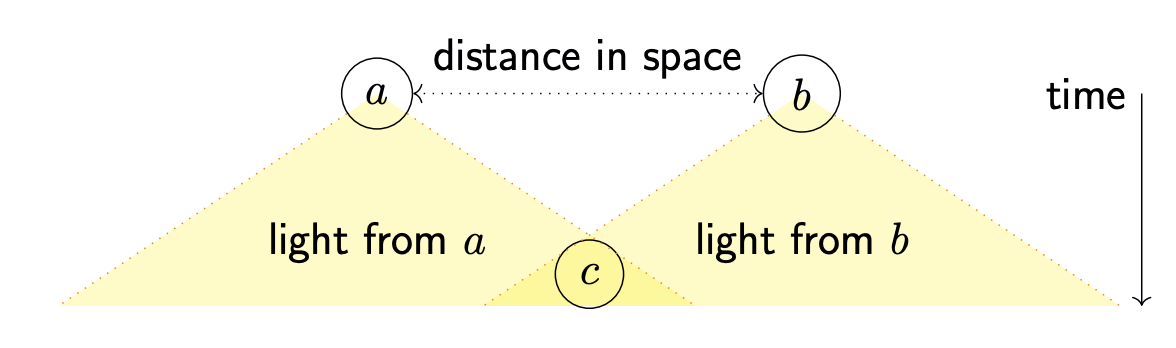

The happens-before relation

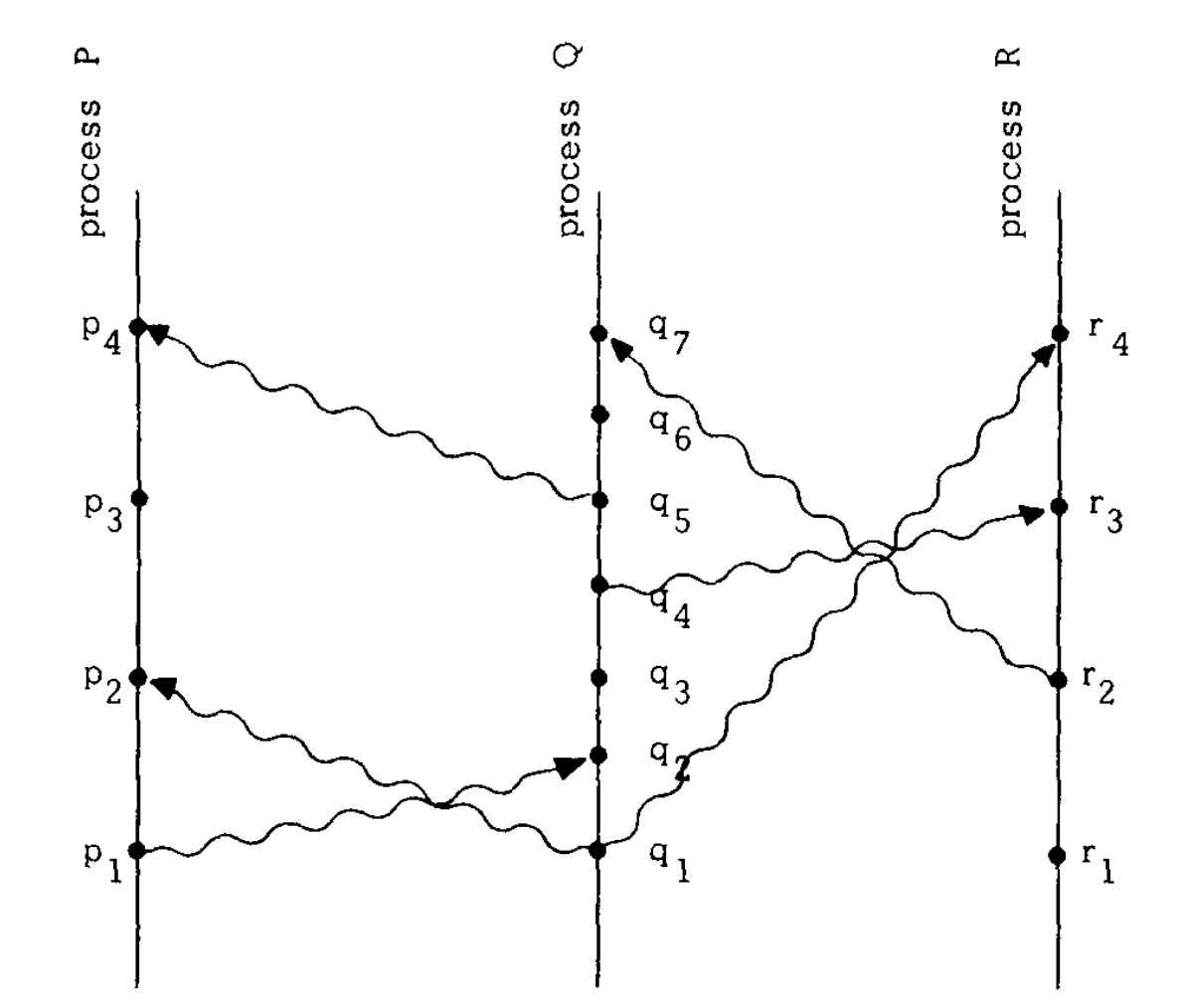

An event is something happening at one node (sending ot receiving a message, or a local execution step).

We say event

- event

- there exists an event

The happens-before relation is a partial order: it is possible that neither

Causality

Taken from physics (relativity).

- When

- When

Happens-before relation encodes potential causality.

If you have two events

Let

If

In the previous example, a happens before b, but in the strict total order, a happens after b, which breaks the above rule, and inconsistent with causality.

(or:

NB. “causal”

Broadcast protocols and logical time

Logical vs. physical clocks

- Physical clock: count number of seconds elapsed

- Logical clock: count number of events occurred

Physical timestamps: useful for many things, but may be inconsistent with causality

Logical clocks: designed to capture causal dependencies

Two types of logical clocks:

- Lamport clocks

- Vector clocks

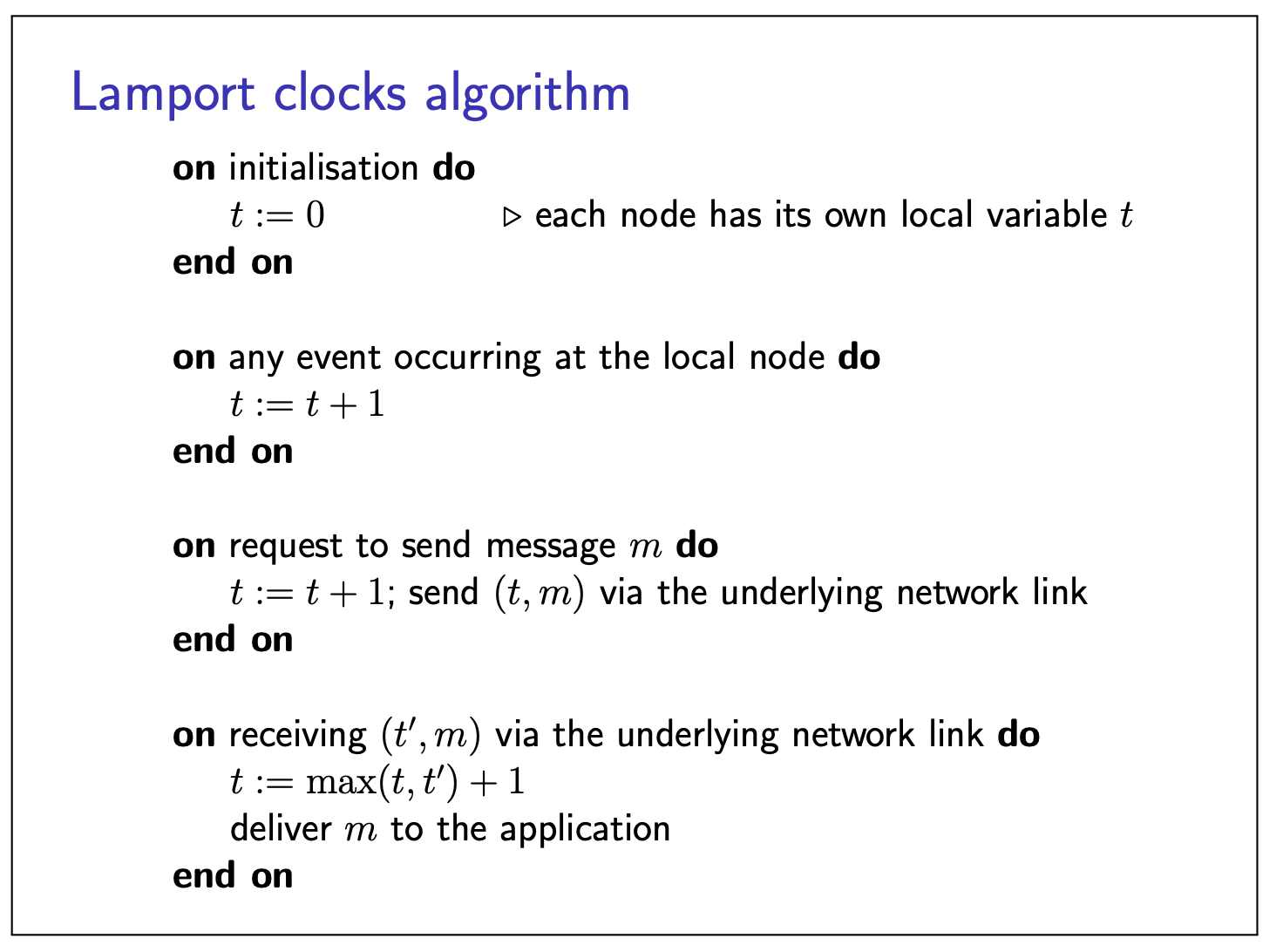

Lamport clocks algorithm

- Each node maintains a counter

- Let

- Attach current

- Recipient moves its clock forward to timestamp in the message (if greater than local counter), then increments

Properties of this scheme:

- If

- However,

- Possible that

Here, we better take a look at the paper written by Lamport in 1978, he gives a more detailed definition of this algorithm.

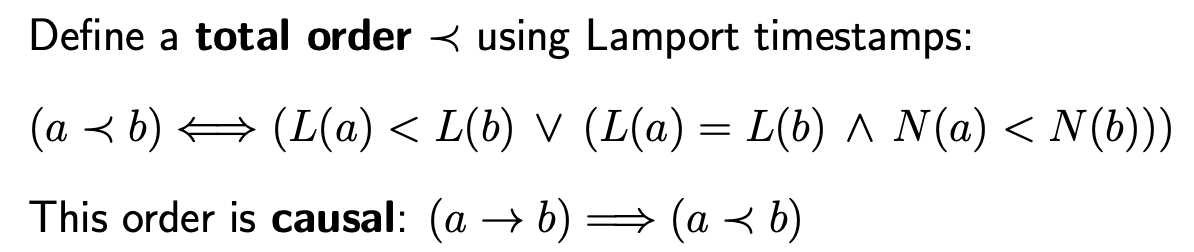

The above logical clocks give a partial order of system events, and we can define a total order

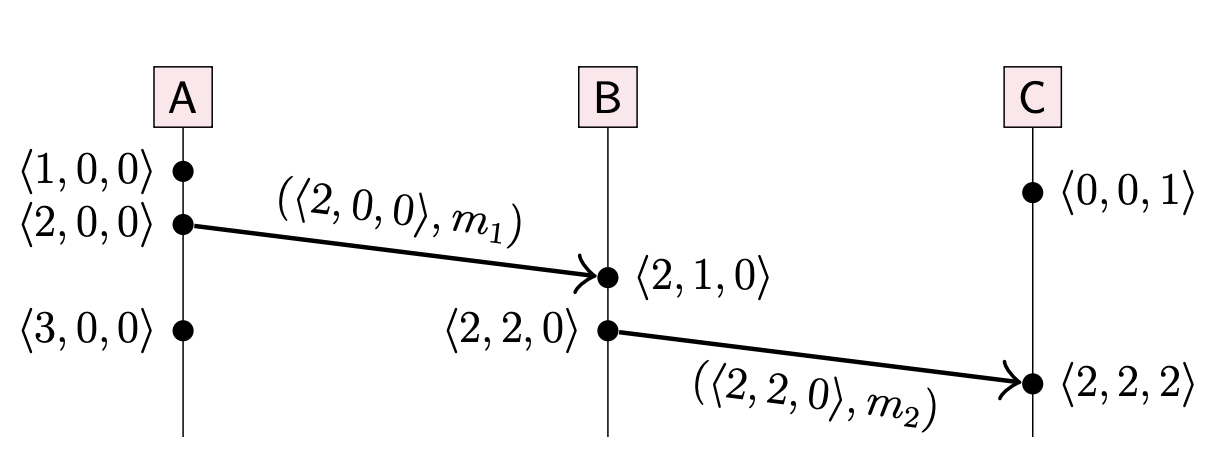

vector clocks

Give Lamport timestampes

It we want to detect which events are concurrent, we need vector clocks:

- Assume

- Vector timestamps of event

- Each node has a current vector timestamp

- On event at node

- Attach current vector timestamp to each message

- Recipient merges message vector into its local vector

The vector timestamp of an event

For example, <2,2,0> represents the first two events from A, the first two events from B, and no events from C.

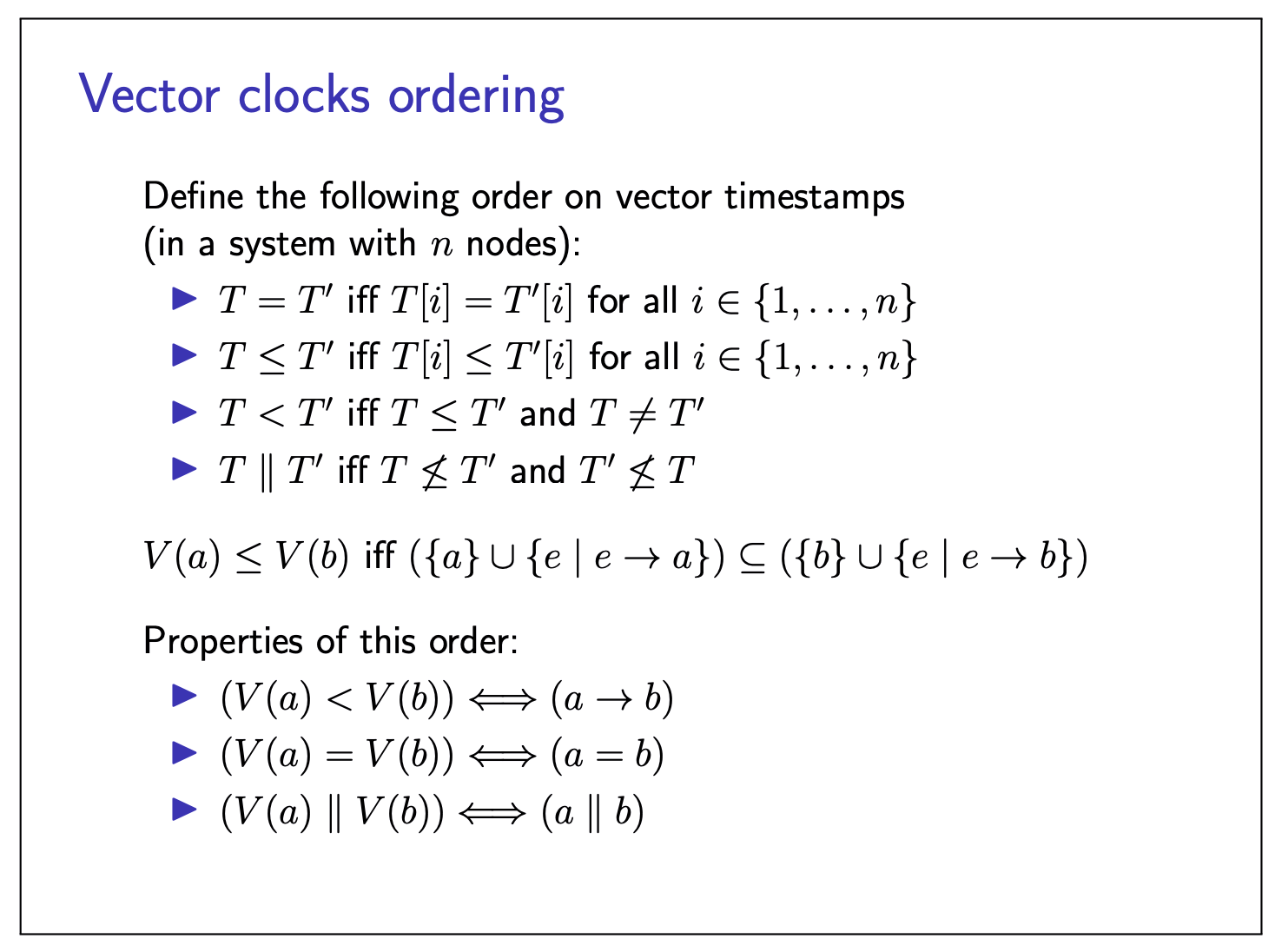

Vector clocks ordering:

Broadcast protocols

Broadcast (multicast) is group communication.

- One node sends message, all nodes in group deliever it

- Set of group members may be fixed (static) or dynamic

- If one node is faulty, remaining group members carry on (tolerance)

- Note: concept is more general than IP multicast (we build upon p2p messaging, some local-area networks provide multicast or broadcast at the hardware level (for example, IP multicast), but communication over the Internet typically only allows unicast. Moreover, hardware-level multicast is typically provided on a best-effort basis, which allows messages to be dropped; making it reliable requires retransmission protocols similar to those discussed here.)

Build on system models:

- Can be best-effort (may drop messages) or reliable (non-faulty nodes deliver every message, by retransmitting dropped messages)

- Asynchronous / partially synchronous timing model (no upper bound on message latency)

Receiving vs. Delivering

Assume network provides p2p send/receive.

After broadcast algorithm receives messages from network, it may buffer/queue it before delivering to the application.

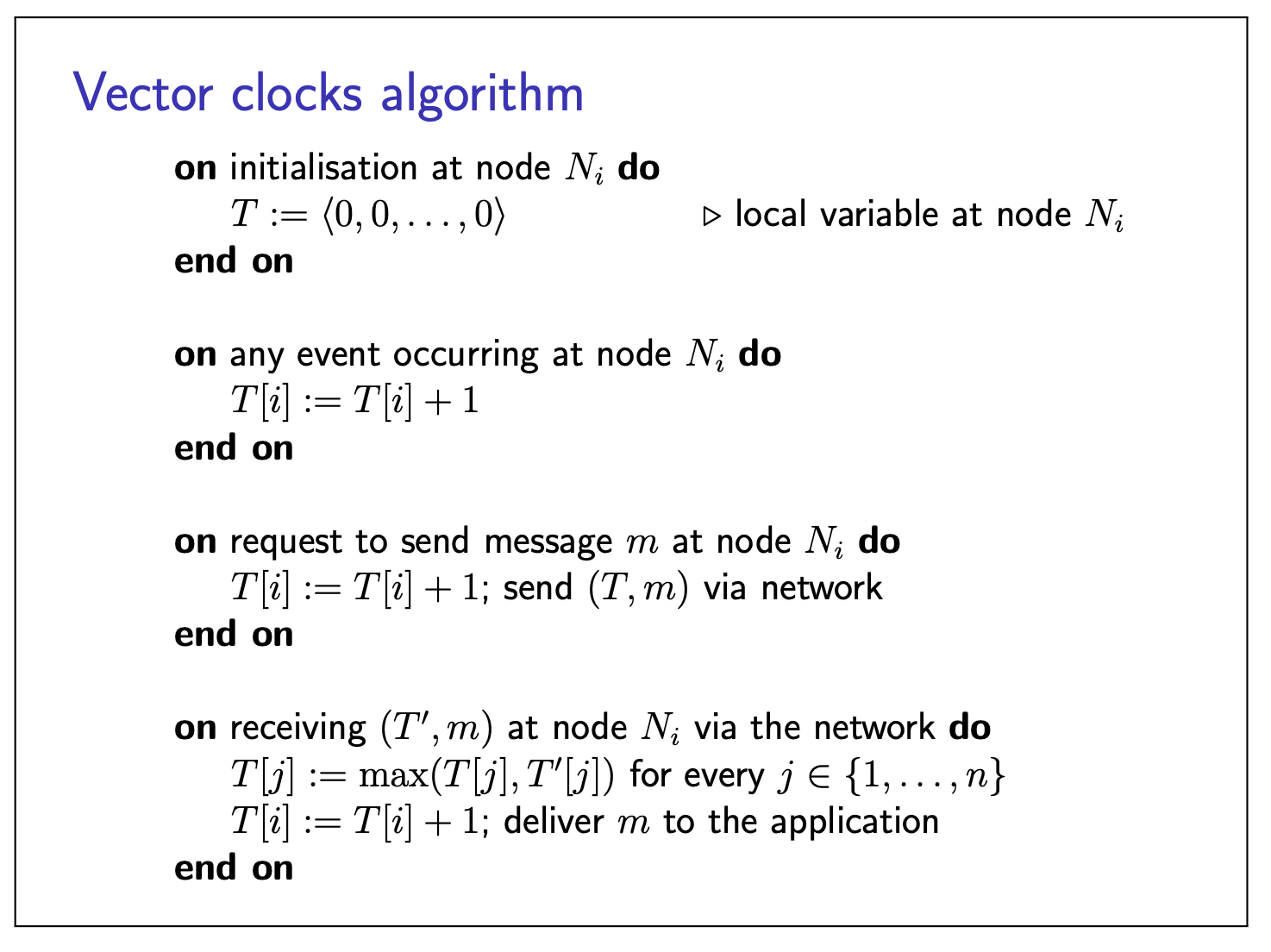

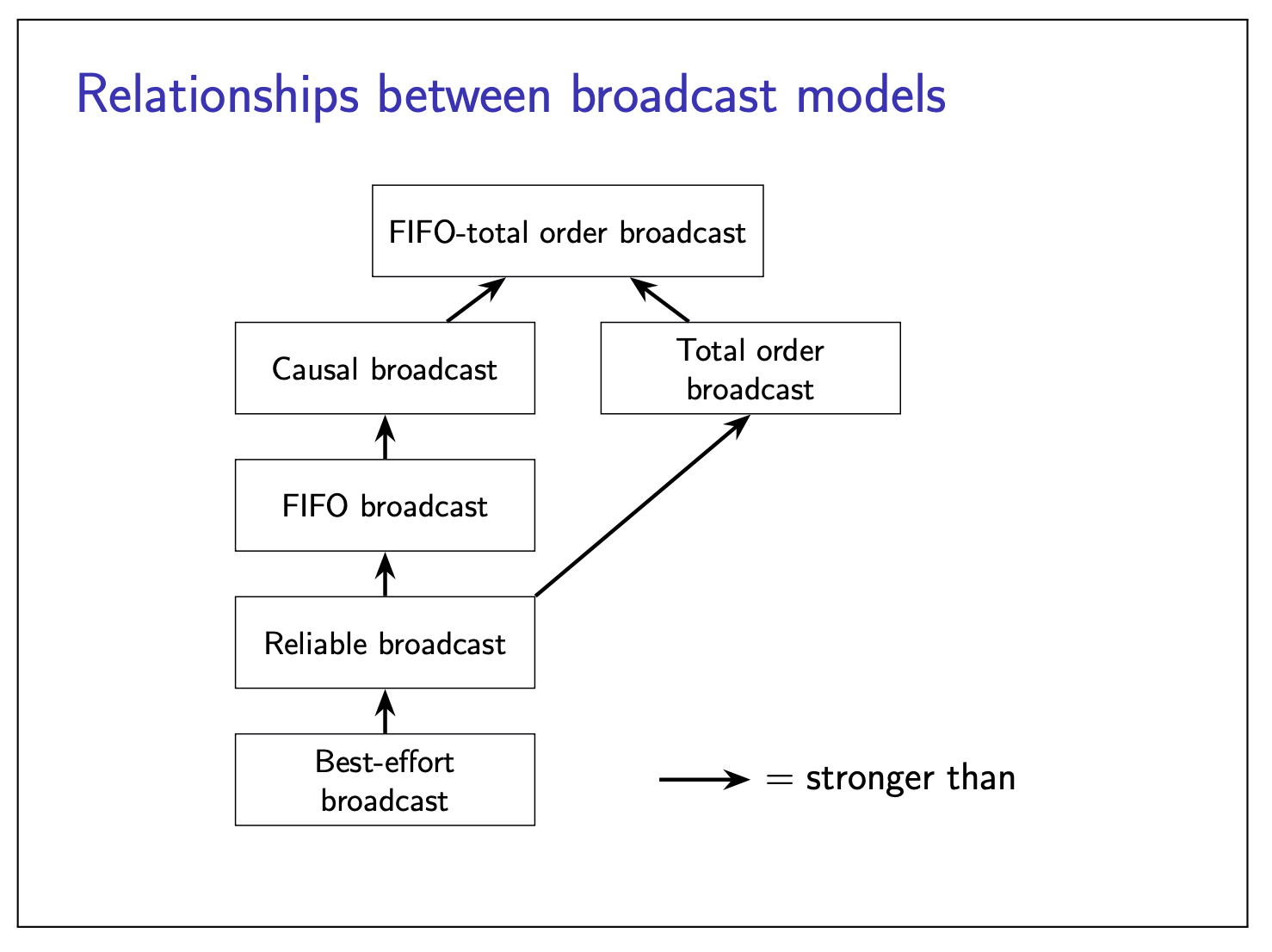

Forms of reliable broadcast

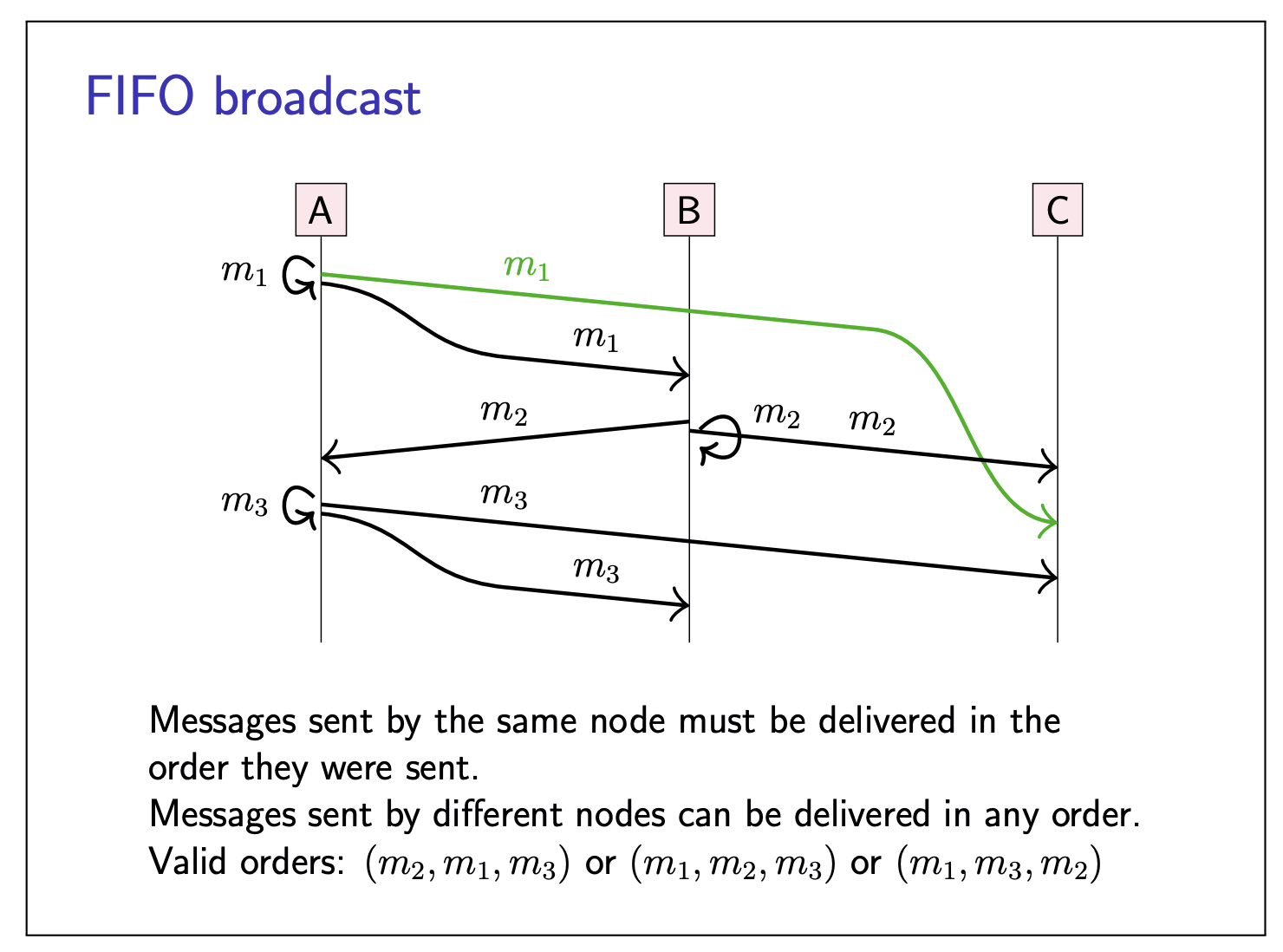

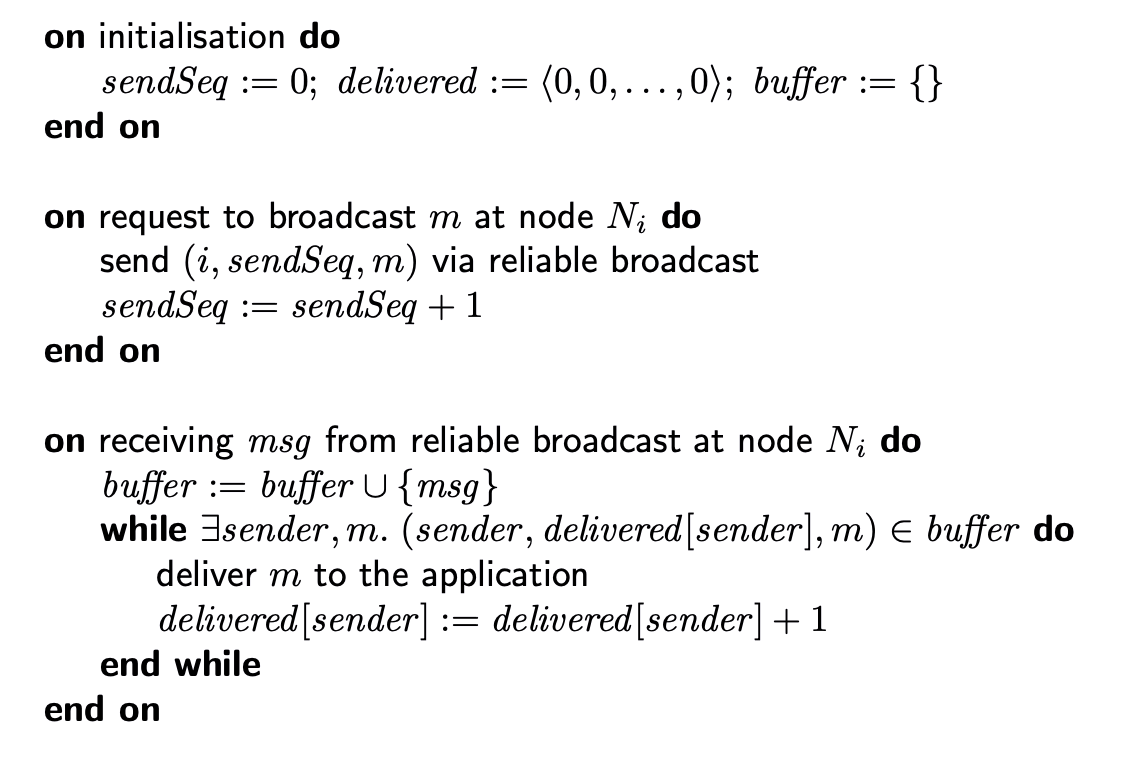

FIFO broadcast:

If

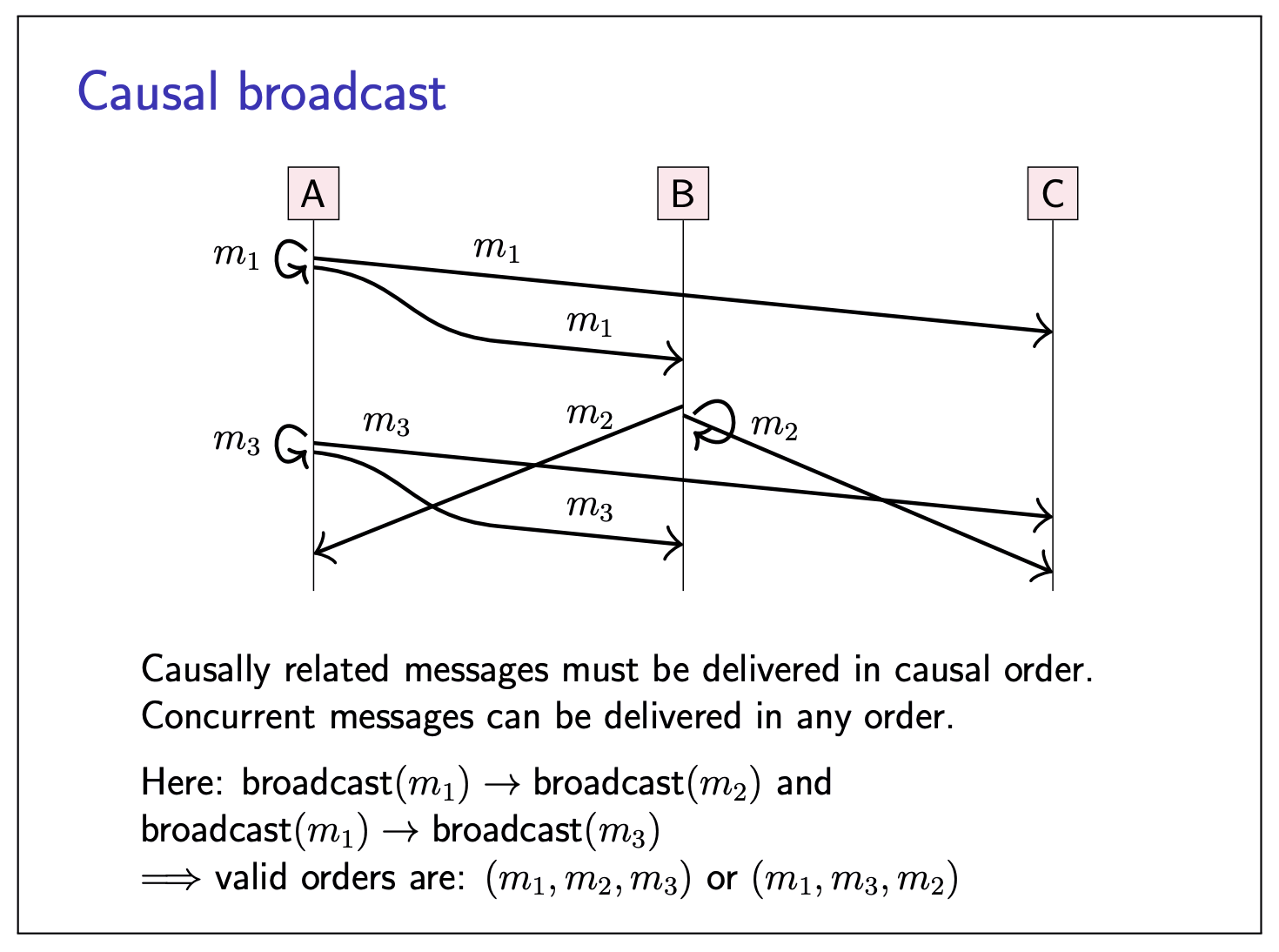

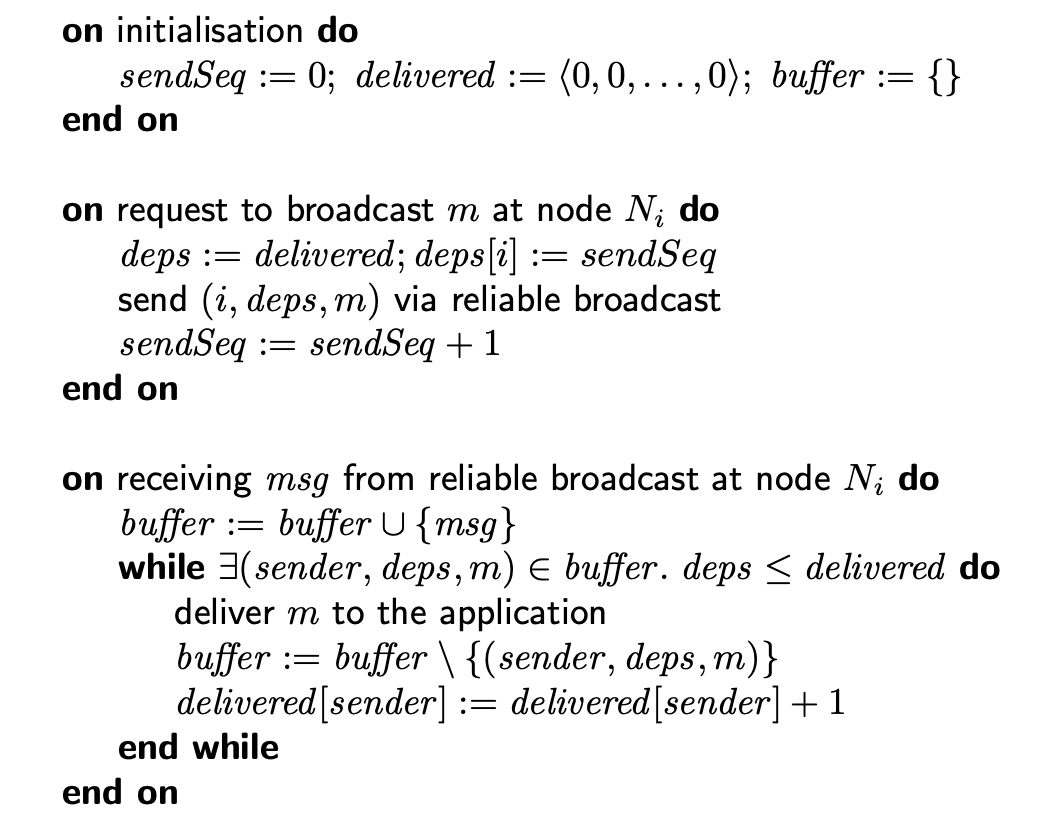

Causal broadcast:

If broadcast(

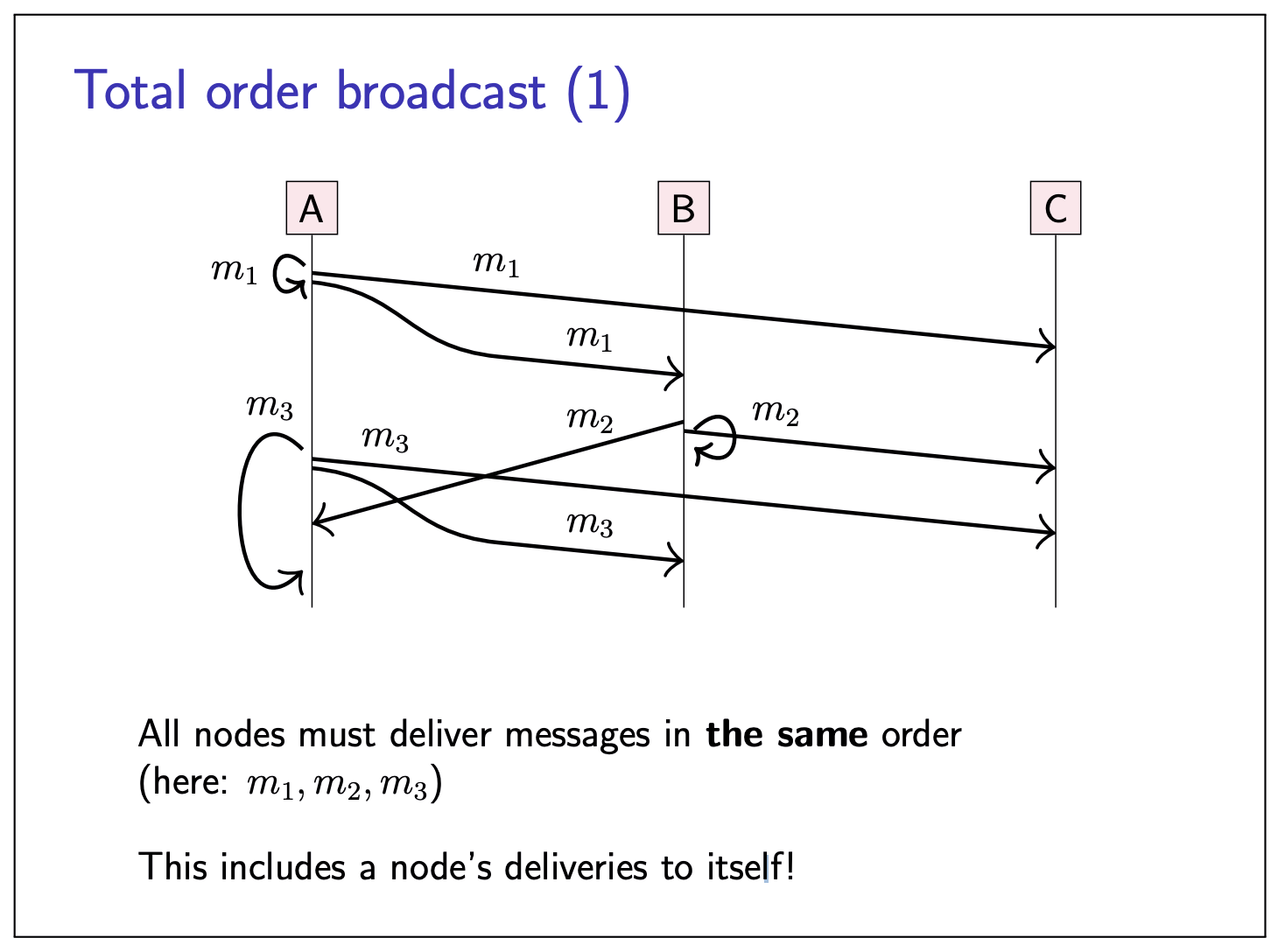

Total order broadcast:

If

Relationship between broadcast models:

Broadcast algorithms

Break down into two layers:

- Make best-effort broadcast reliable by retransmitting dropped messages

- Enforce delivery order on top of reliable broadcast

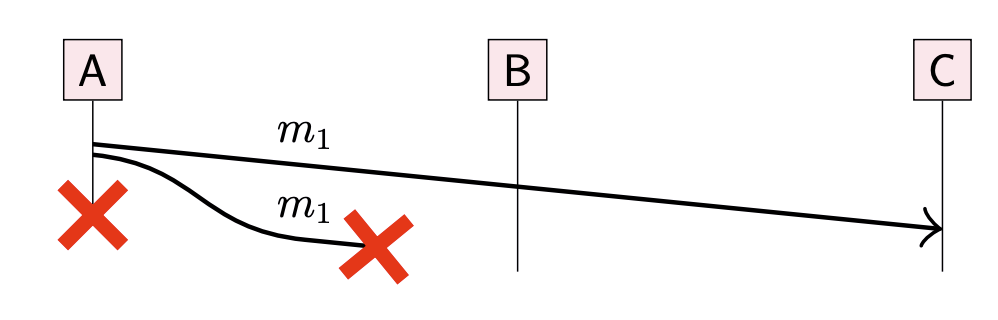

First attempt: broadcasting node sends message directly to every other node

- Use reliable links (retry + deduplicate)

- Problem: node crash before all messages delivered

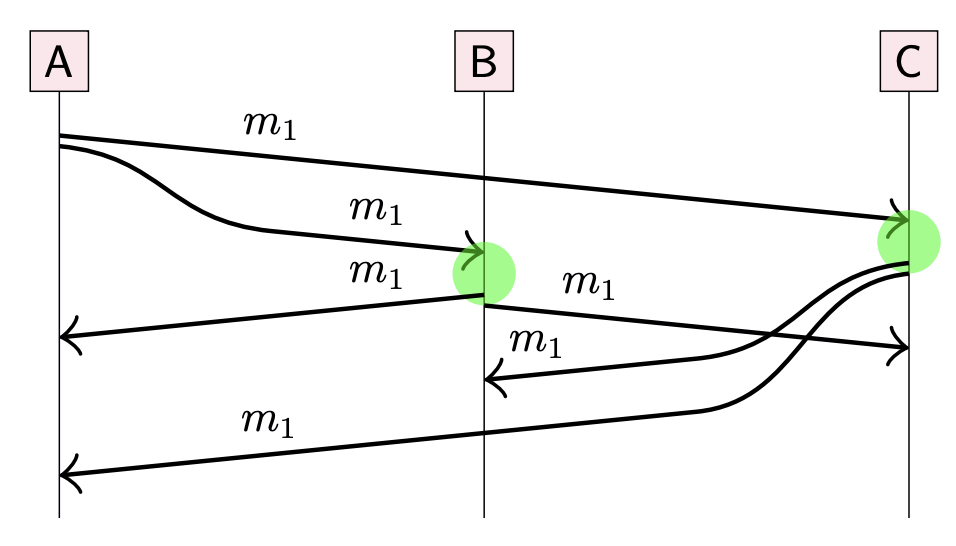

Eager reliable broadcast

Idea: the first time a node receives a particular message, it re-broadcasts to each other node (via reliable links).

Reliable, but up to

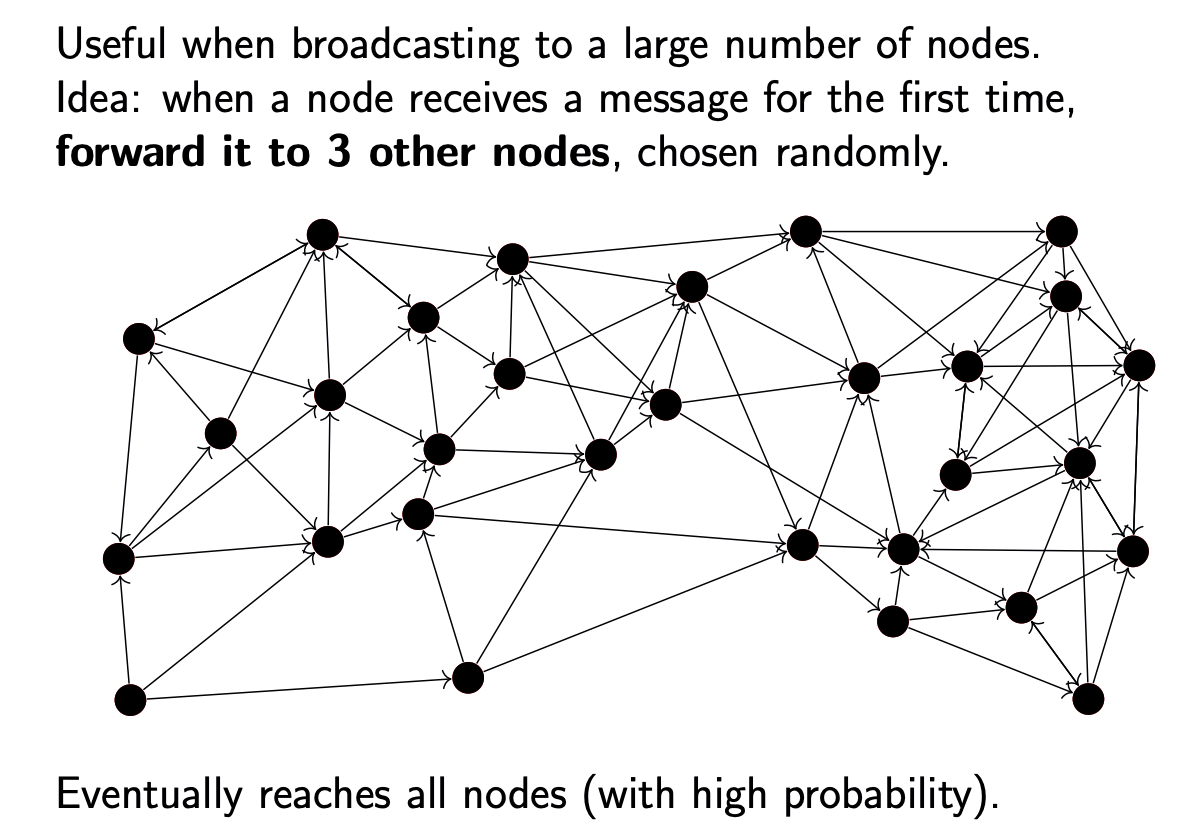

Gossip protocols:

FIFO/causal/total order broadcast algorithm

| FIFO | Causal | total order |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

Replication

- Keeping a copy of the same data on multiple nodes

- Databases, filesystems, caches, …

- A node that has a copy of the data is called a replica

- If some of the replicas are faulty, others are still accessible

- Spread load across many replicas

- Easy if the data does not change: just copy it

- We will focus on data changes

Compare to RAID: replication within a single computer

- RAID has single controller; in distrbuted system, each node acts independently

- Replicas can be distributed around the world, near users

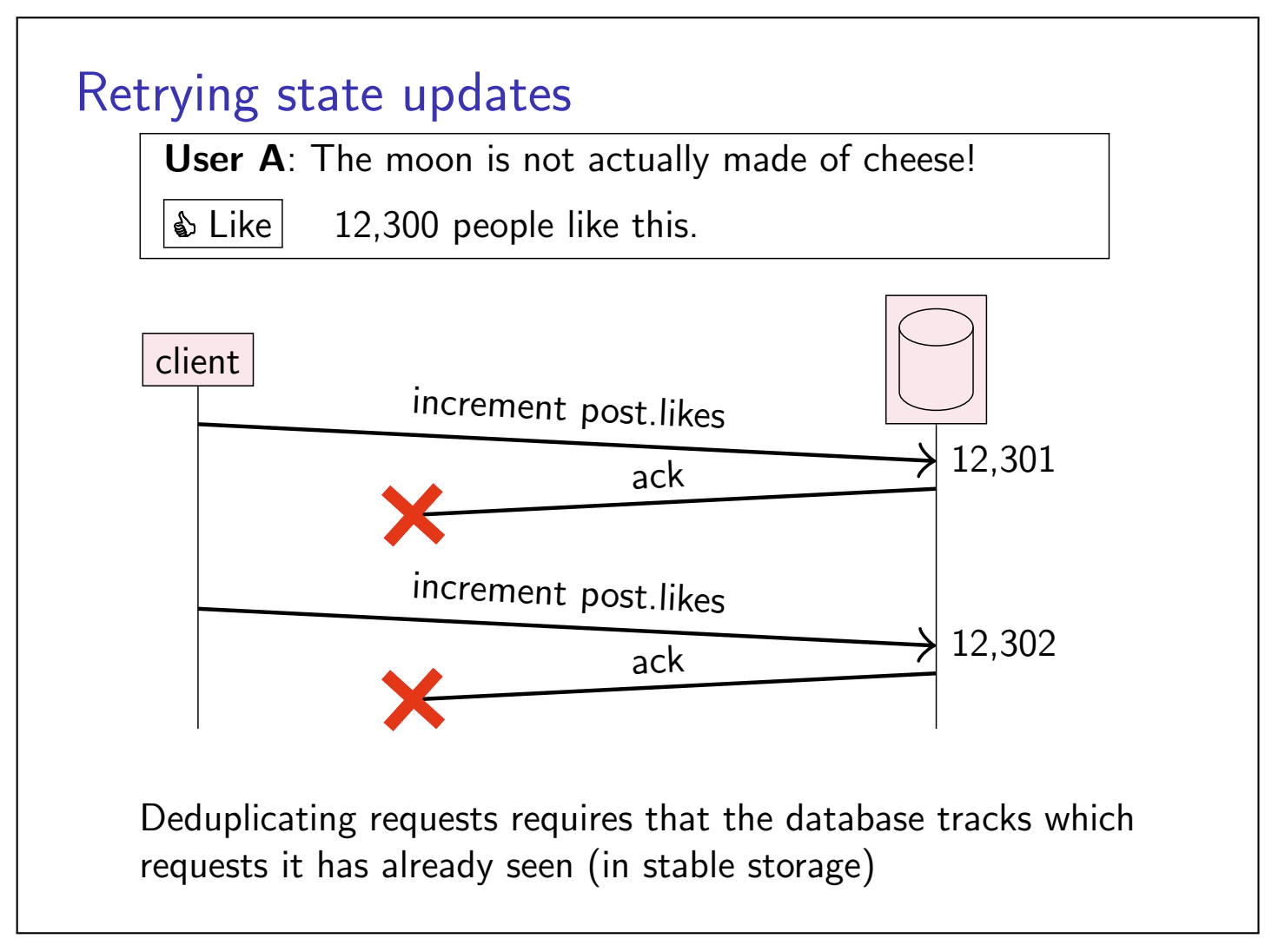

When we try to deduplicate the requests, in a crash-recovery system model, this requires storing requests (or some metadata about requests, such as a vector clock) in stable storage, so that duplicates can be accurately detected even after a crash.

An alternative to recording requests for deduplication is to make requests idempotent.

idempotent

A fucntion

- Not idempotent:

- Idempotent:

Idempotent requests can be trtried without deduplication.

Choice of retry behavior:

At-most-once semantics:

send request, don’t retry, update may not happen

At-least-once semantics:

retry request until acknowledged, may repeat update

Exactly-once semantics:

retry+idempotence or deduplication

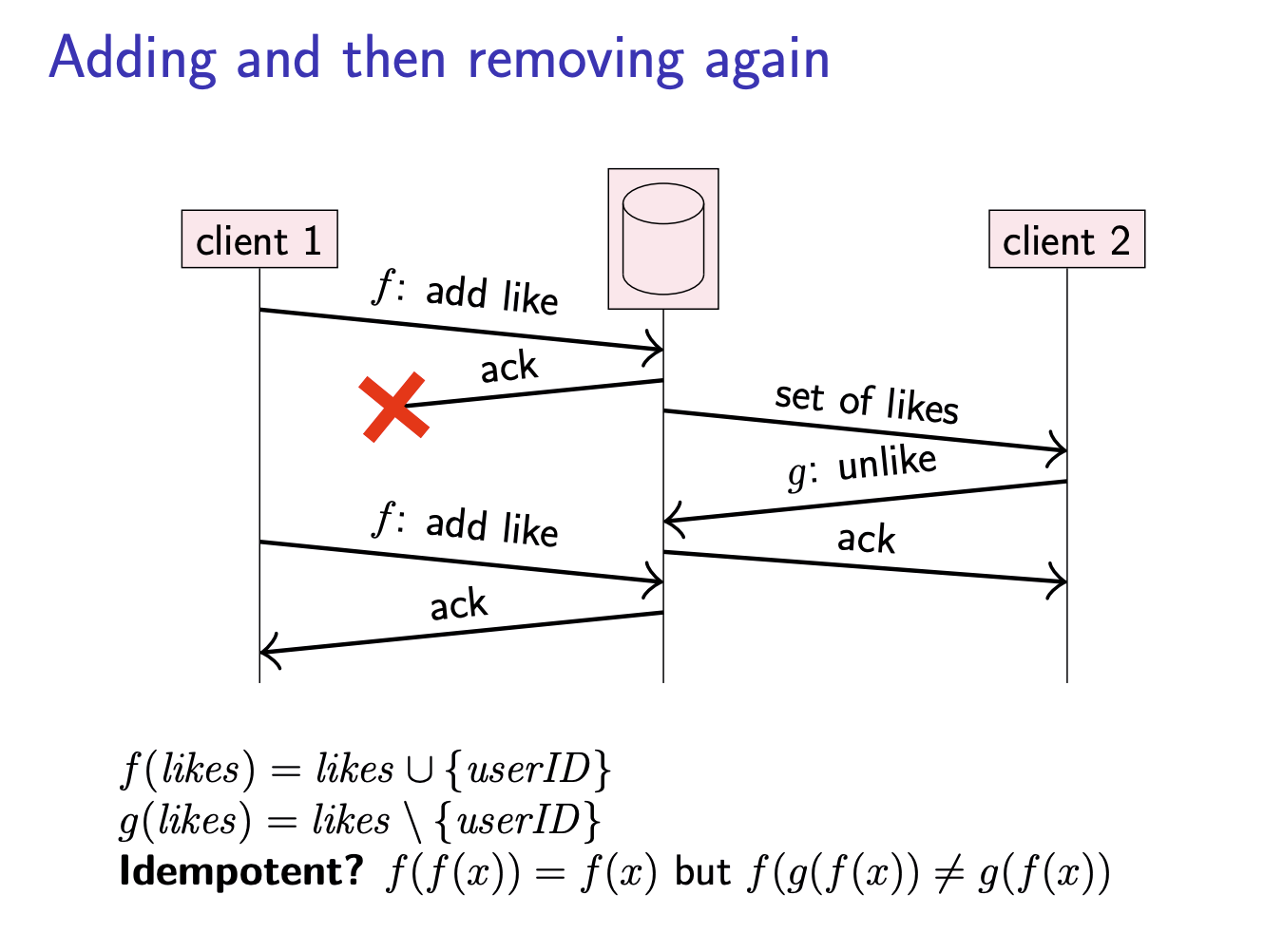

But there are also some problems of using idempotence.

Adding and then removing again

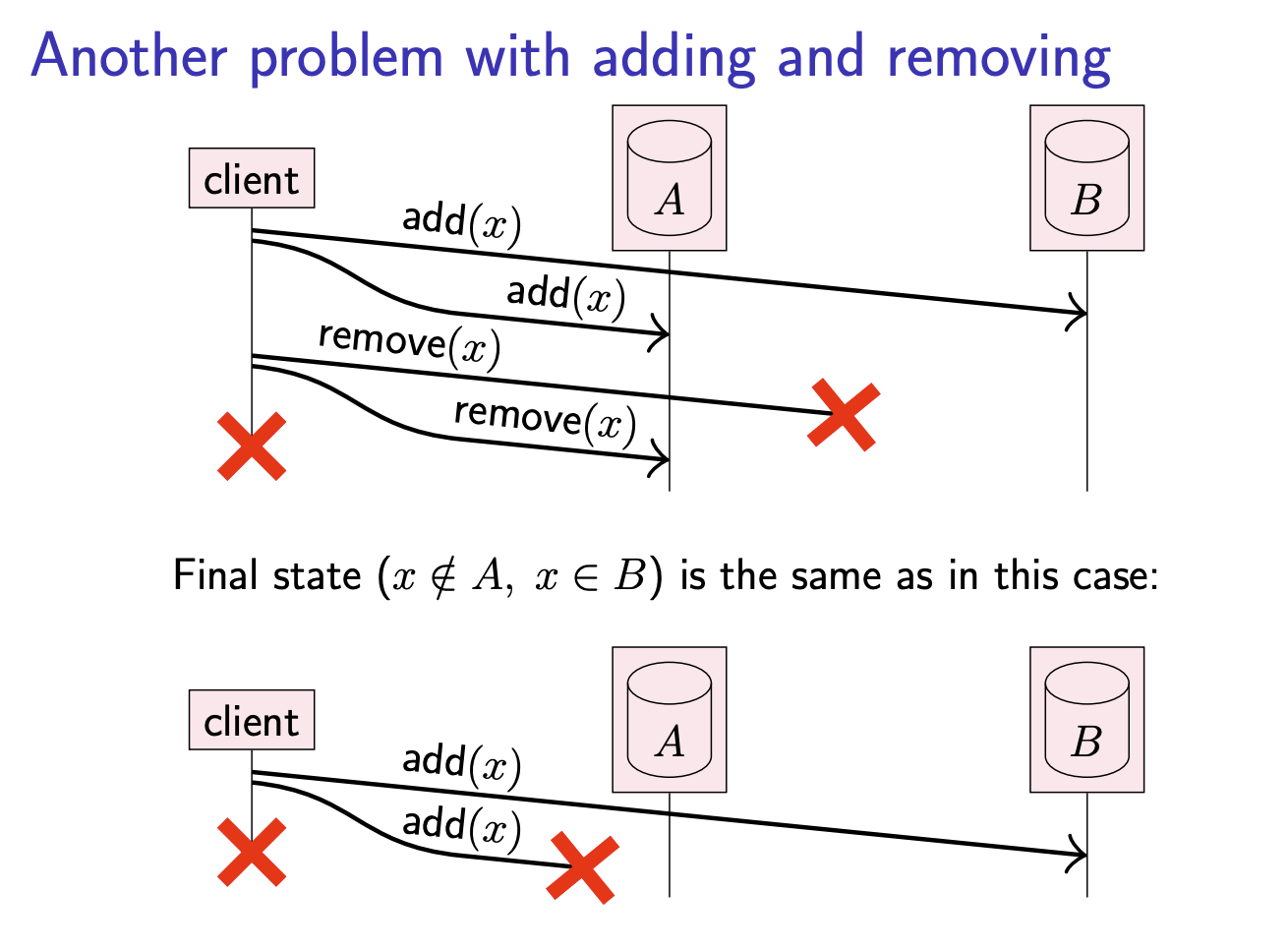

Another problem with adding and removing

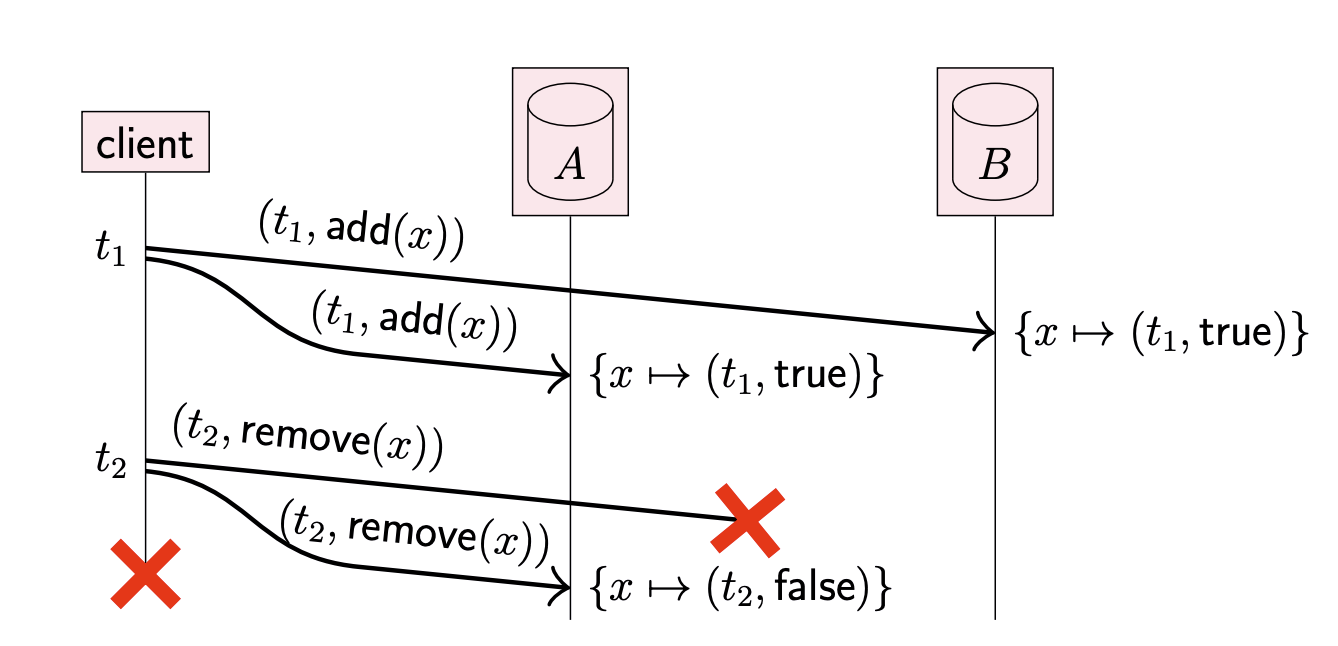

Here. arises another problem: When the two replicas reconcile their inconsistent states, we want them to both end up in the state that the client intended. However, this is not possible if the replicas cannot distinguish between these two scenarios. To solve this problem, we can use timestamps and tombstones.

timestamps and tonbstones

“Remove(

Every record has logical timestamp of last write.

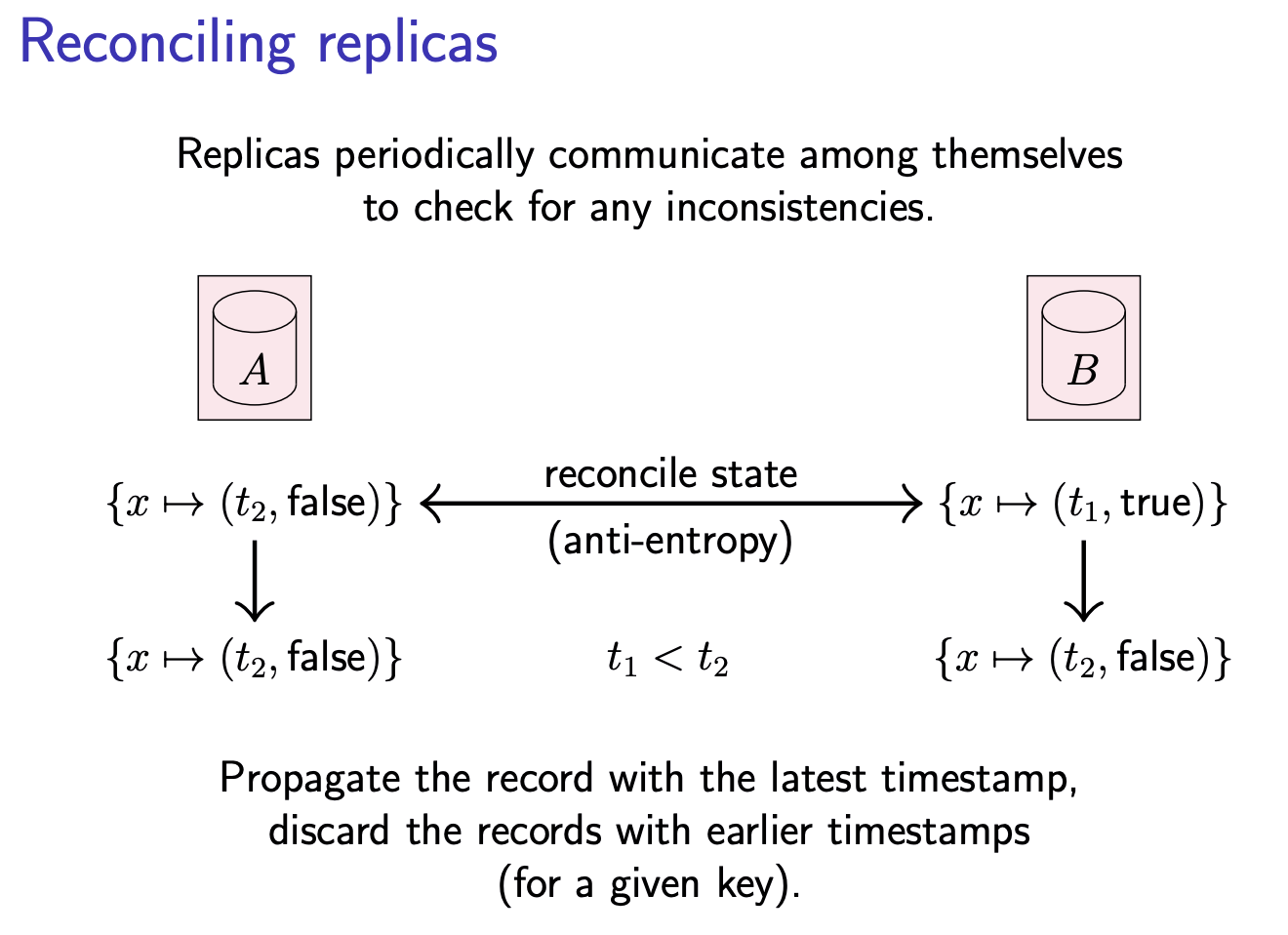

In many replicated systems, replicas run a protocol to detect and reconcile any differences (this is called anti-entropy), so that the replicas eventually hold consistent copies of the same data. Thanks to tombstones, the anti-entropy process can tell the difference between a record that has been deleted and a record that has not yet been created. And thanks to timestamps, we can tell which version of a record is older and which is newer. The anti-entropy process then keeps the newer and discards the older record.

Reconciling Replicas

We can use lamport clocks or vector clocks to fulfil this goal.

Two common apporaches:

Last writer wins (LWW)

Use timestamps with total order (e.g. Lamport clock). Keep

Since when using the Lamport clock total order, we cannot distinguish between the events with “happens-before” relationship and the events happen concurrently. As a result, we cannot split the concurrent events from the system events group.

The update with the greatest timestamp takes effect, and any concurrent updates with lower timestamps to the same key are discarded. This approach is simple to work with, but it does imply data loss when multiple updates are performed concurrently. Whether or not this is a problem depends on the application: in some systems, discarding concurrent updates is fine.

When discarding concurrent updates is not acceptable, we need to use a type of timestamp that allows us to detect when updates happen concurrently, such as vector clocks. With such partially ordered timestamps, we can tell when a new value should overwrite an old value (when the old update happened before the new update), and when several updates are concurrent, we can keep all of the concurrently written values. These concurrently written values are called conflicts, or sometimes siblings. The application can later merge conflicts back into a single value.

Multi-value register

Use timestamps with partial order (e.g. vector clock).

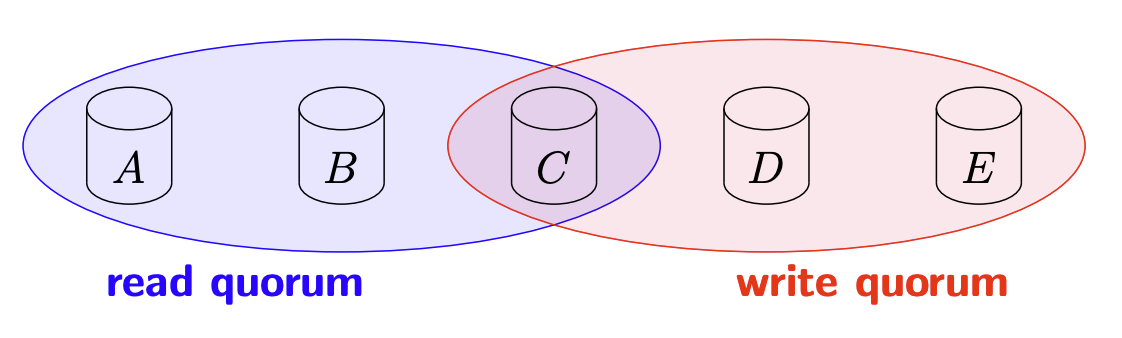

Quorums

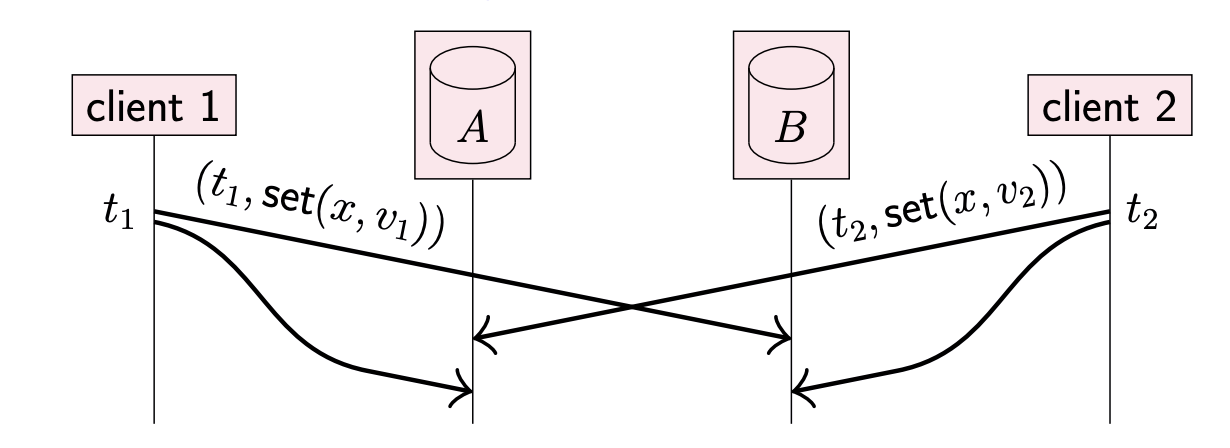

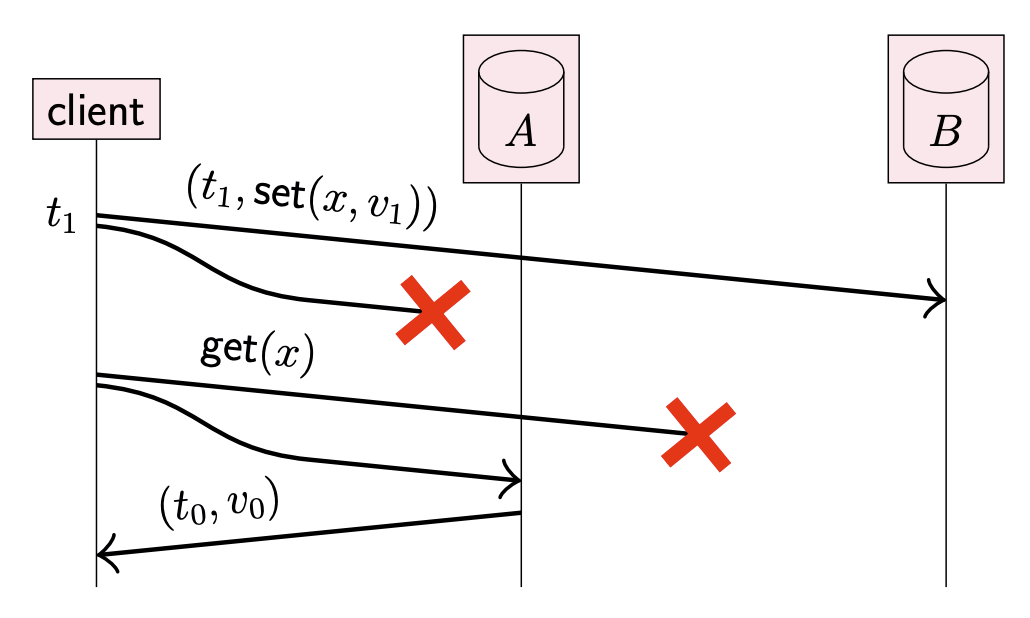

Read-After-Write Consistency

Writing to one replica, reading from another: client does not read back the value it has written.

require writing to/reading from both replicas

We can use Quorum to solve this problem.

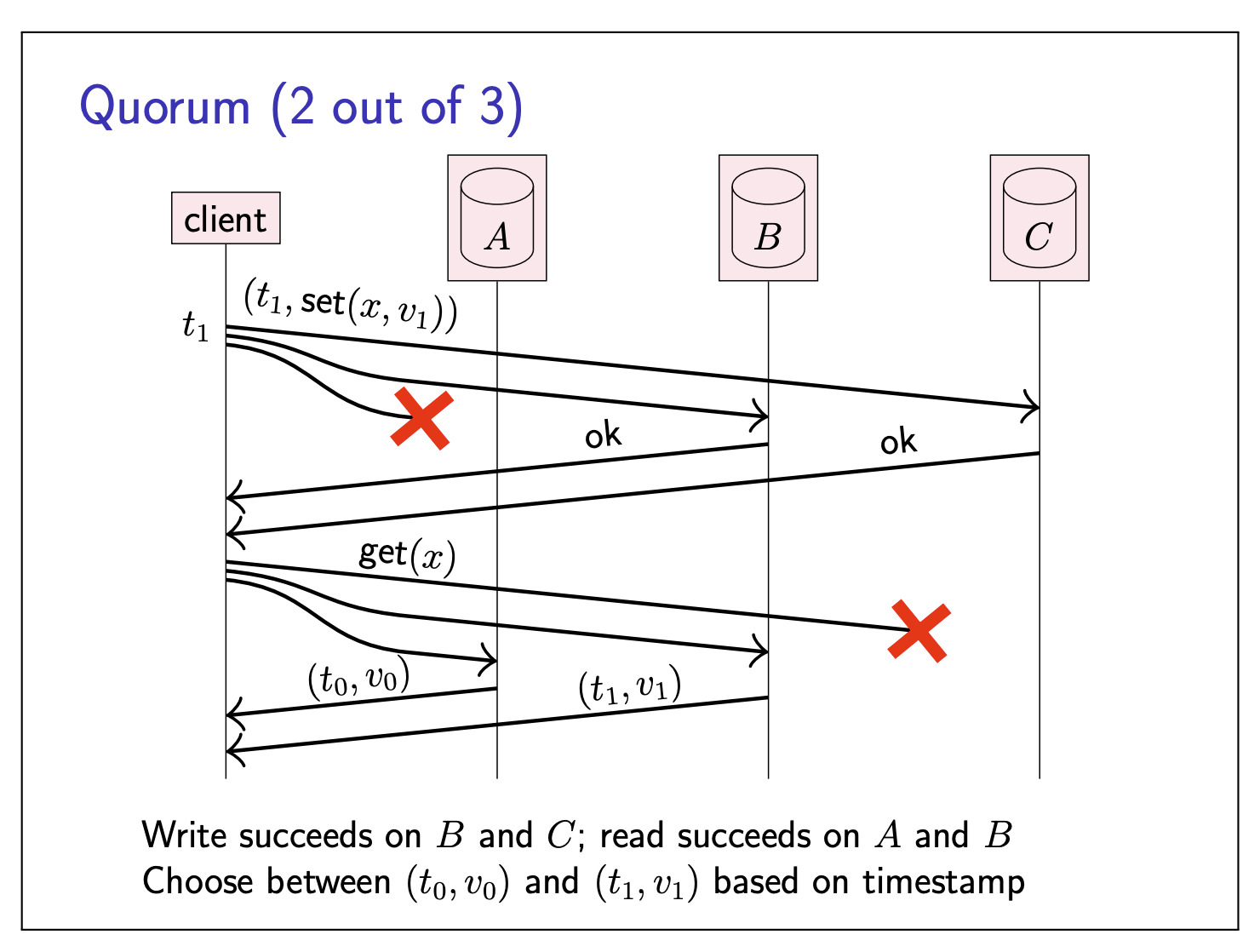

Now we give an example of using Quorum:

Read and write quorums

In a system with

- If a write is acknowledged by

- and we subsequently read from

- and

- then the read will see the previously written value (or a value that subsequently overwrote it)

- Read quorum and write quorum share

- Typical:

- Reads can tolerate

Note:

- If we wanna read the most recent data: If we already knows the version number of the most recent committed data, read

- If we wanna read the most recent committed data/version number: …, read until the highest version number appears

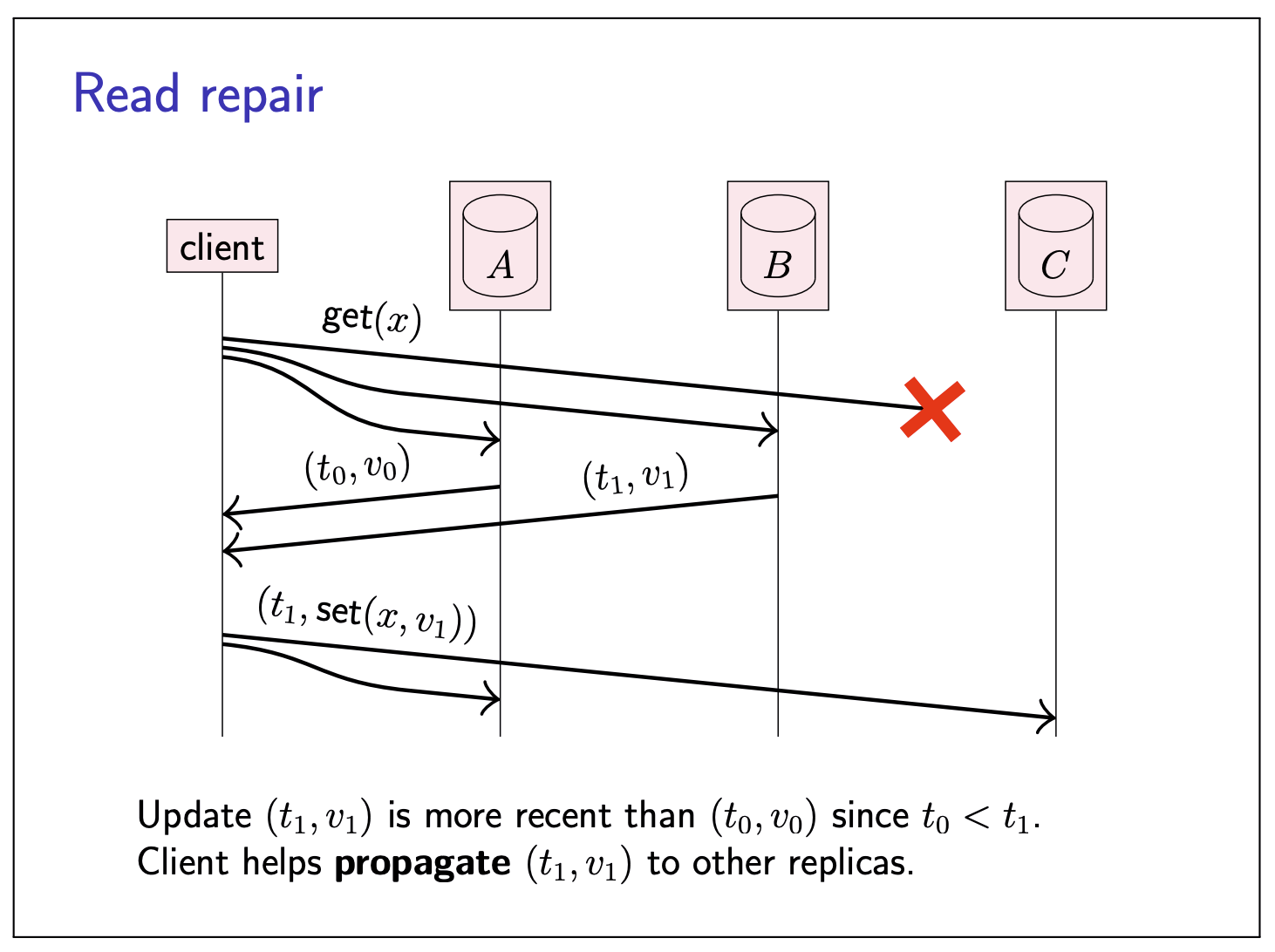

Read repair

In this quorum approach to replication, some updates may be missing from some replicas at any given moment, since that write request was dropped. To bring replicas back in sync with each other, one approach is to rely on an anti-entropy process mentioned before.

Or, we can use something called read repair:

Since the client now knows that the update

Databases use this model of replication are often called Dynamo-style, after Amazon’s Dynamo database, which popularized it.

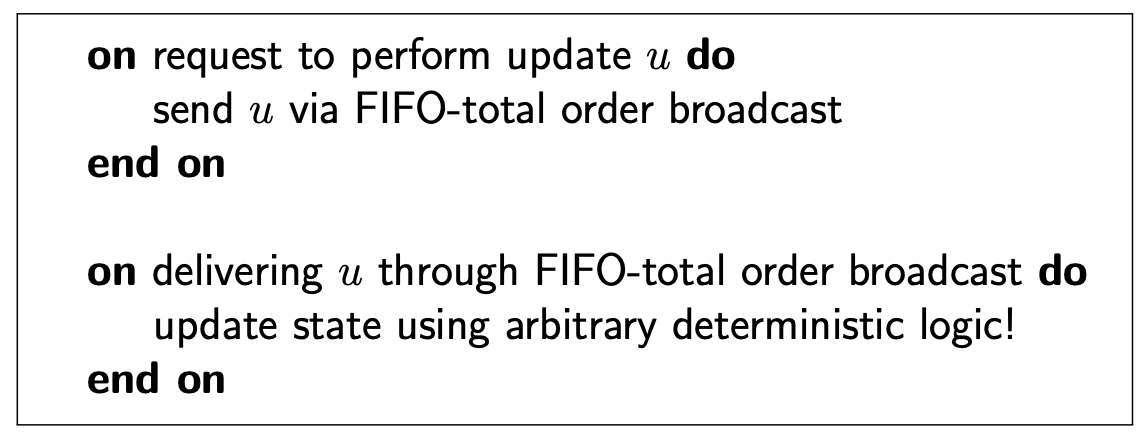

State machine replicaiton

Total order broadcast: every node delivers the same messages in the same order.

State machine replication (SMR):

- FIFO-total order broadcast every update to all replicas

- Replica delivers update message: apply it to own state

- Applying an update is deterministic

- Replica is a state machine: starts in fixed initial state, goes through same sequence of state transaitions in the same order

Closely related ideas:

- Serializable transactions (execute in delivery order)

- Blockchains, distributed ledgers, smart contracts

Limitations:

- Cannot update state immediately, have to wait for delivery through broadcast (wait for the coordination between replicas)

- Need fault-toleratn total order broadcast

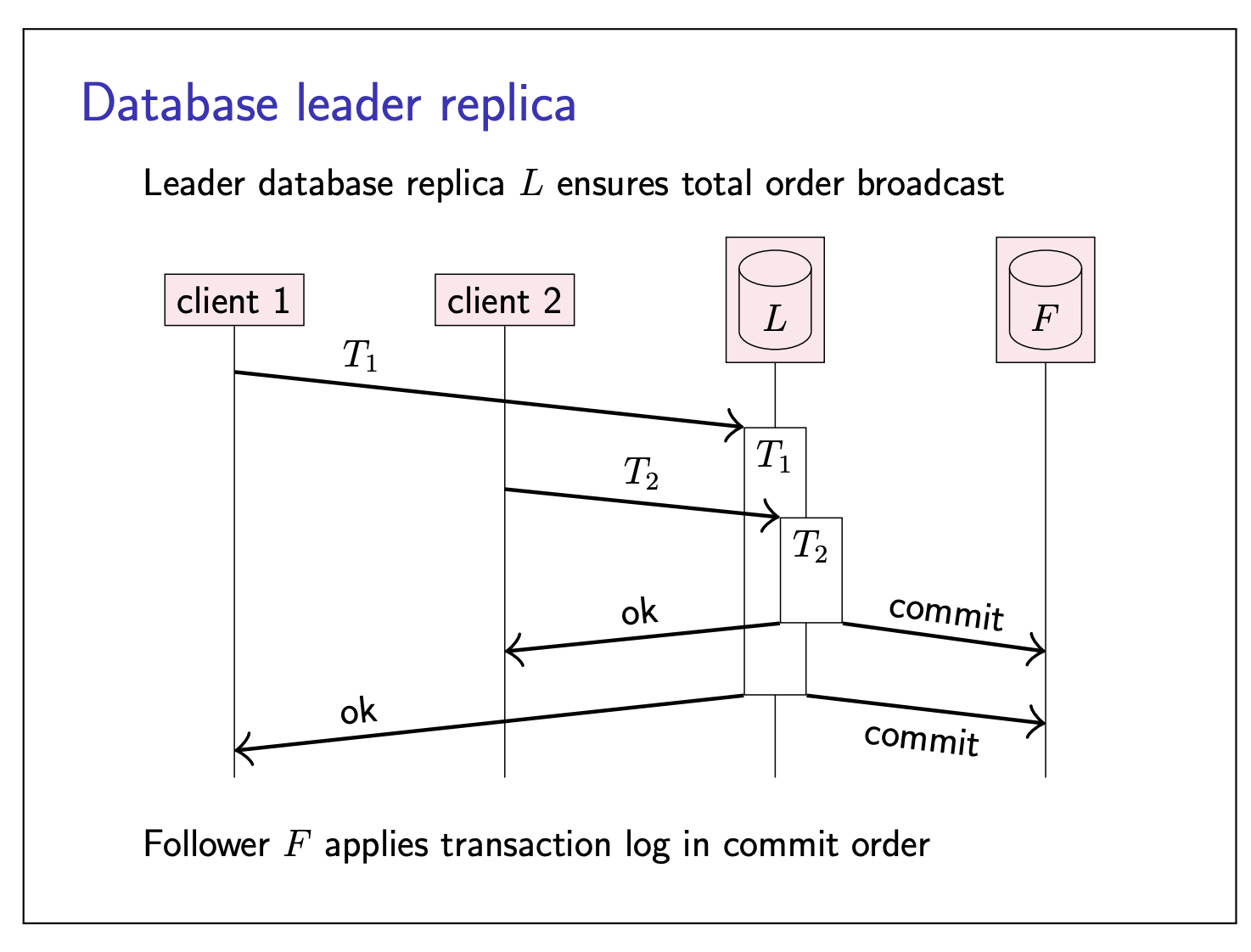

Database leader replica

Read-only transactions can execute on followers, transactions that modify data must execute on leader first.

Replication using casusal (and weaker) broadcast

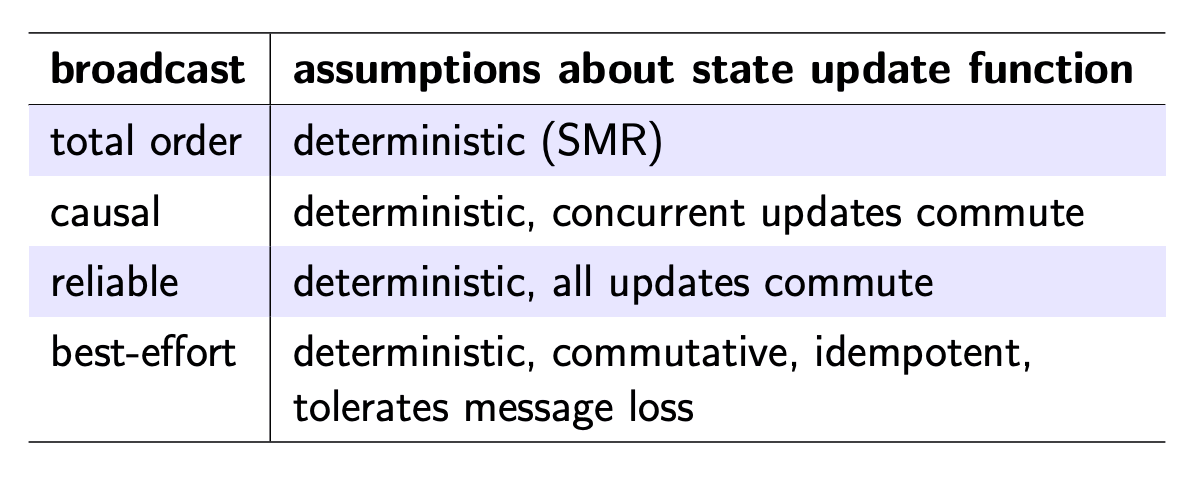

State machine replication uses (FIFO-) total order broadcast. Can we use weaker forms of broadcast too?

If replica state updates are commutative, replicas can process updates in different orders and still end up in the same state.

Updates

Consensus

Fault-tolerant total order broadcast

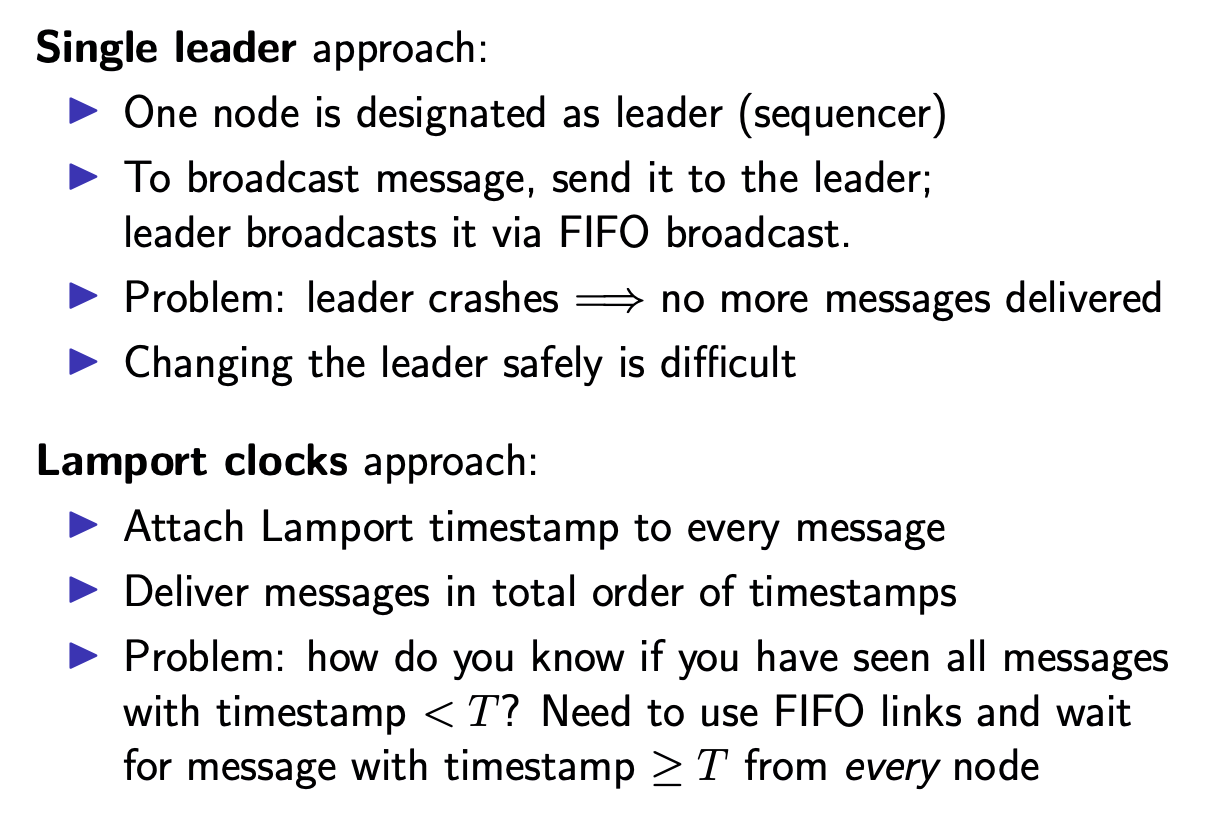

Total order broadcast is very useful for state machine replication.

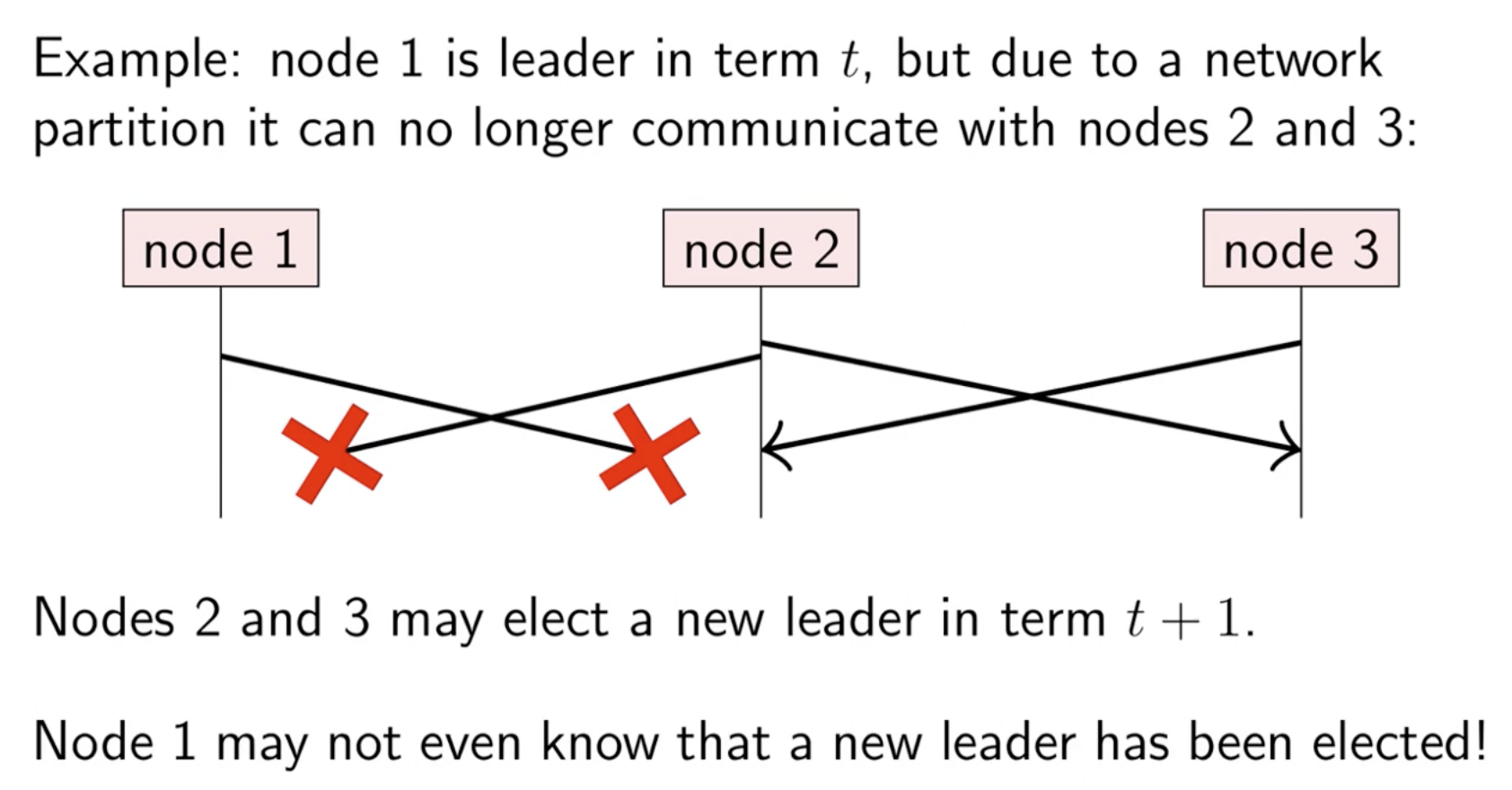

Can implement total order broadcast by sending all messages via a single leader.

Problem: what if leader crashes/becomes unavailable?

Manual failover: a human operator chooses a new leader, and reconfigures each node to use new leader

Used in many databases! Fine for planned maintaienance.

Unplanned outage? Humans are slow, may take a long time until system recovers…

Can we automatically choose a new leader?

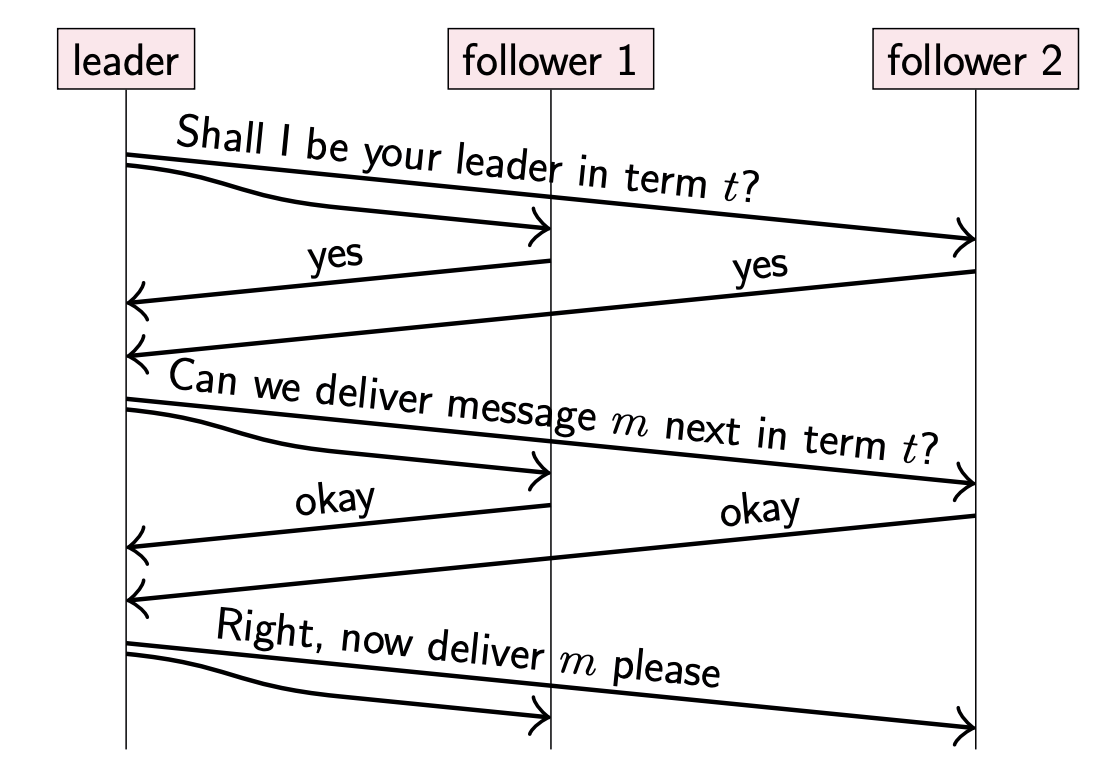

Consensus and total order broadcast

- Traditional formulation of consensus: several nodes want to come to agreement about a single value

- In context to total order broadcast: this value is the next message to deliver

- Once one node decides on a certain message order, all nodes will decide the same order

- Consensus and total order broadcast are formually equivalent

Common consensus algorithms:

Paxos: single-value consensus

Multi-Paxos: generalization to total order broadcast

Raft, Viewstanped Replication, Zab: total order broadcast by default

Consensus system models

Paxos, Raft, etc. assume a partially synchronous, crash-recovery system model.

Why not asynchronous?

FLP result (Fischer, Lynch, Paterson, impossibility proven)

There is no deterministic consensus algorithm that is guaranteed to terminate in an synchronous crash- stop system model.

Paxos, Raft, etc. use clocks only used for timeouts/failure detector to ensure progress. Safety (correctness) does ot depend on timing.

There are also consensus algorithms for a partially syncronous Byzantine system model (used in blockchains).

Leader election

Multi-Paxos, raft, etc. use a leader to sequence messages.

- Use a failure detector (timeout) to determine suspected crash or unavailaility of leader.

- On suspected leader crash, elect a new one.

- Prevent two leaders at the same time (“split-brain”)

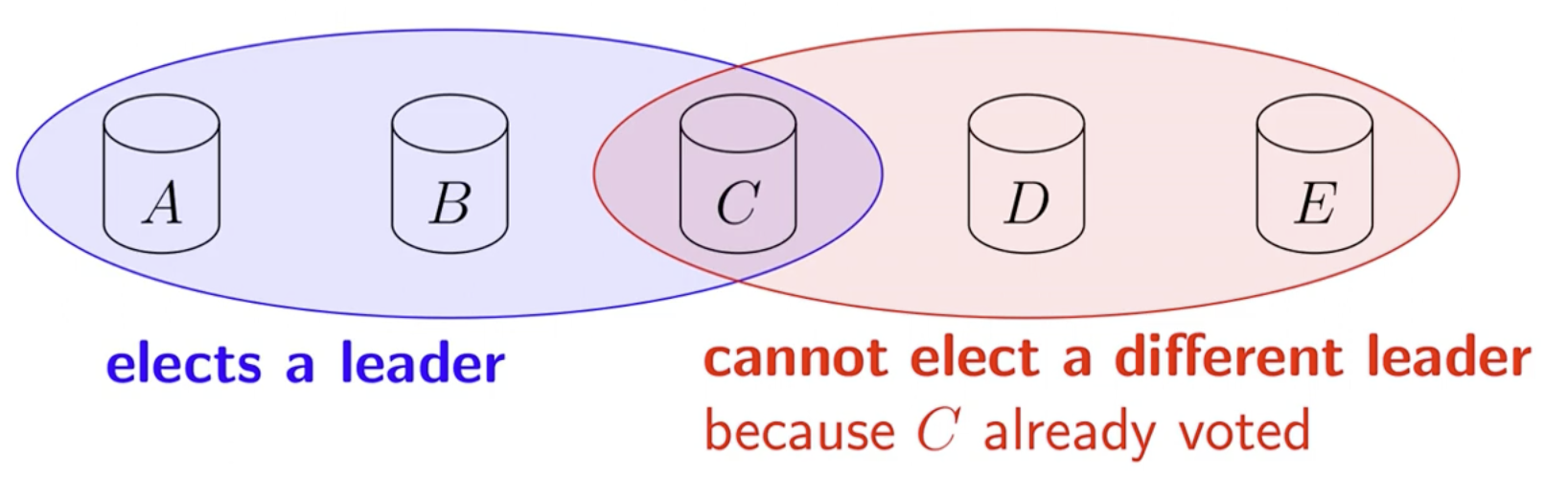

Ensure

- Term is incremented every time a leader election is started

- A node can only vote once per term

- Require a quorum of nodes to elect a leader in a term

Can we guarantee there is only one leader?

Can guarantee unique leader per term.

Cannot prevent having multiple leaderts from different terms.

checking if a leader has been voted out

For every decision (message to deliver), the leader must first get acknowledgement from a quorum.

Raft

This part is omitted since I have already implemented raft algorithm in MIT 6.824.

Replica consistency

Consistency

A word that means many different things in different contexts.

ACID: a transaction the database from one “consistent” state to another

Here, “consistent”=satisfying application-specific invariants

e.g. “every course with students enrolled must have at least one lecturer”

Read-after-write concsistency: this is the consistency defined in the lecture 5 (also in the CAP theorem)

e.g. inconsistent system & consisten system Replication: replica should be “consistent” with other replicas

Consistency model: many to choose from

Distributed transactions

Recall atomicity in the context of ACID transactions:

- A transaction either commit or aborts

- If it commits, its updates are durable

- If it aborts, it has no visible side-effects

- ACID consistency (repserving invariants) relies on atomicity

If the transaction updates data on multiple nodes, this implies:

- Either all ndoes must commit, or all must abort

- If any nodex crashes, all must abort

Ensuring this is the atomic commitment problem. Looks a bit similar to consensus?

Atomic commit versus consensus

| Consensus | Atomic Commit |

|---|---|

| One or more nodes propose a value | Every node votes whether to commit or abort |

| Any one of the proposed values is decided | Must commit if all nodes vote to commit; must abort if |

| Crashed nodes can be tolerated, as long as a quorum is working | Must abort if a participating node crashes |

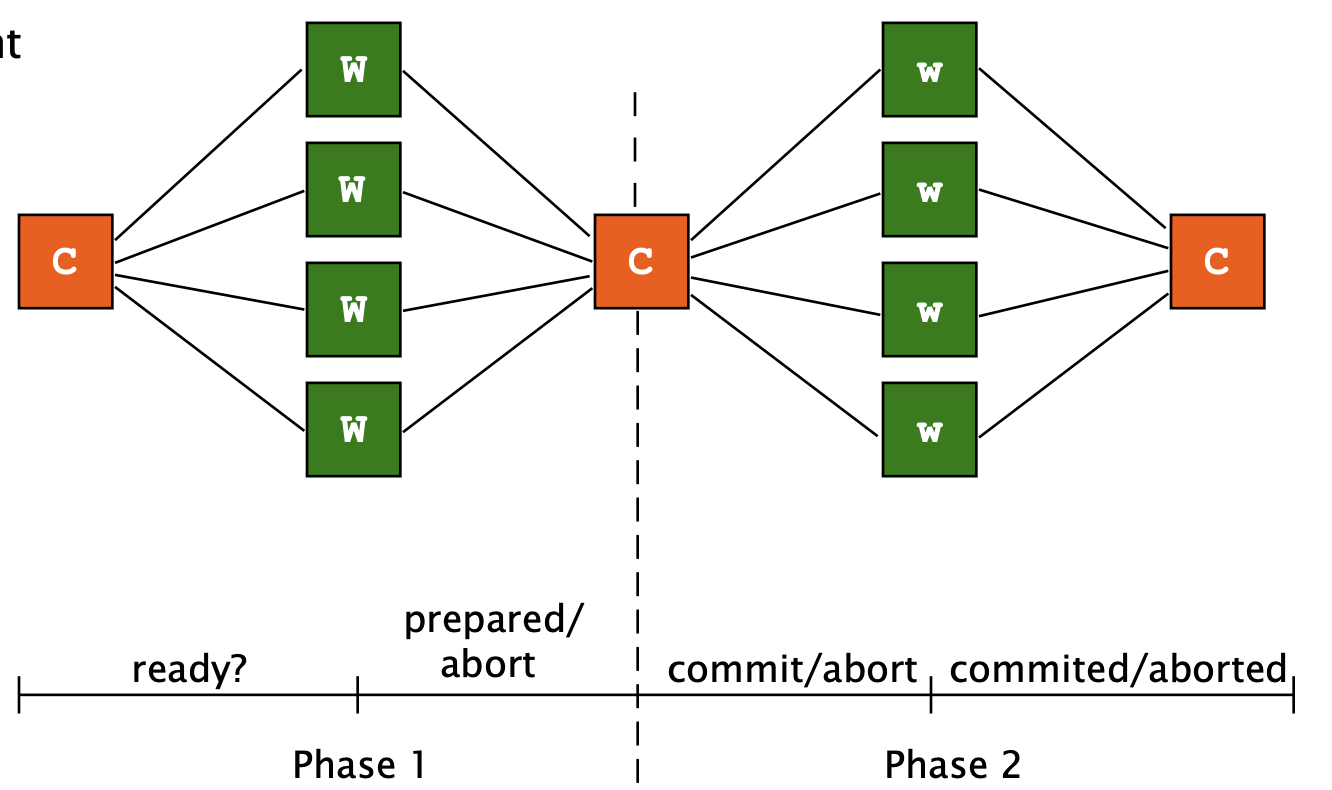

Two-phase commit (2PC)

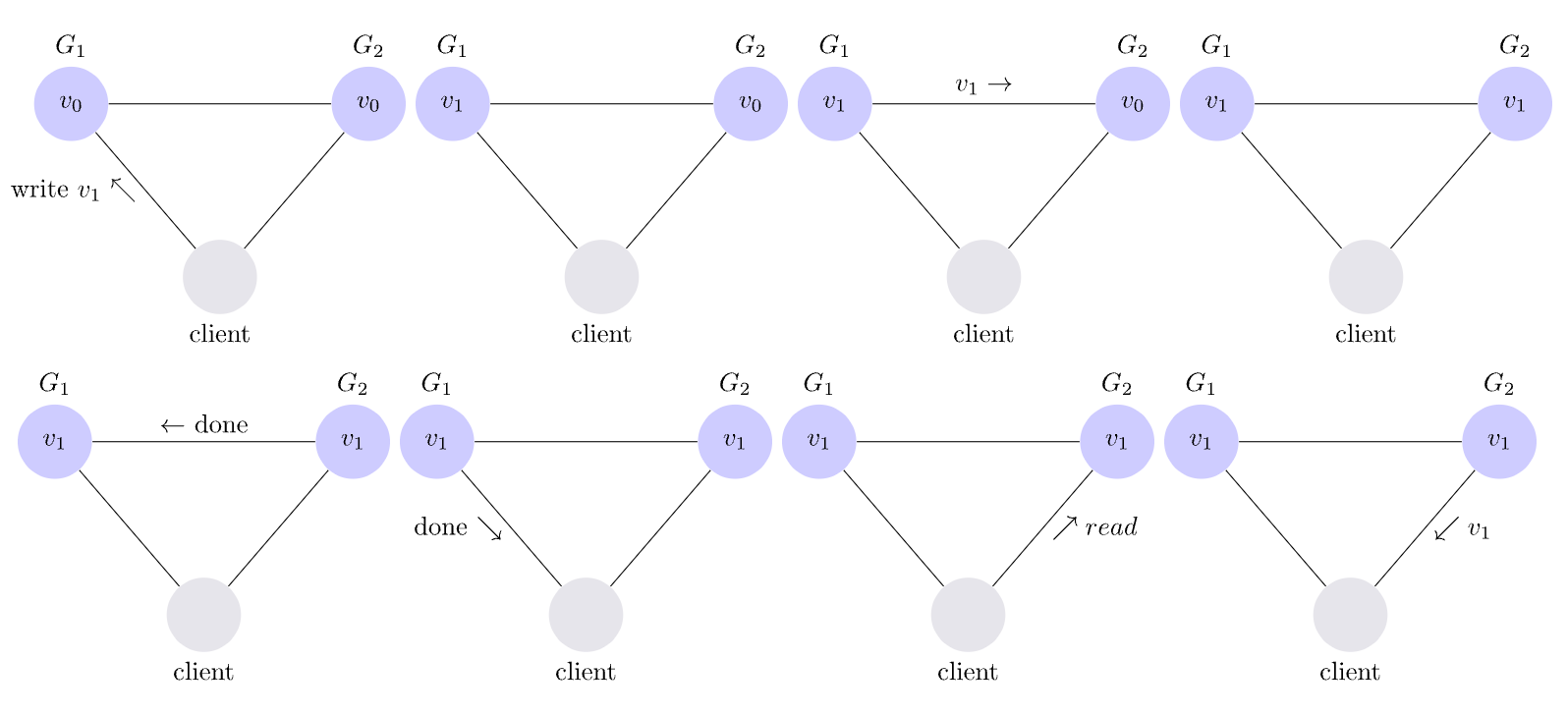

When using two-phase commit, a client first starts a regular single-node transaction on each replica that is participating in the transaction, and performs the usual reads and writes within those transactions. When the client is ready to commit the transaction, it sends a commit request to the transaction coordinator, a designated node that manages the 2PC protocol. (In some systems, the coordinator is part of the client.) The coordinator first sends a prepare message to each replica participating in the transaction, and each replica replies with a message indicating whether it is able to commit the transaction (this is the first phase of the protocol). The replicas do not actually commit the transaction yet, but they must ensure that they will definitely be able to commit the transaction in the second phase if instructed by the coordinator. This means, in particular, that the replica must write all of the transaction’s updates to disk (write a

PREPARErecord to the disk) and check any integrity constraints before replying ok to the prepare message, while continuing to hold any locks for the transaction. The coordinator collects the responses, and decides whether or not to actually commit the transaction. If all nodes reply ok, the coordinator decides to commit; if any node wants to abort, or if any node fails to reply within some timeout, the coordinator decides to abort. The coordinator then sends its decision to each of the replicas, who all commit or abort as instructed (this is the second phase). If the decision was to commit (then the slave will fsyncCOMMITrecord to the WAL log), each replica is guaranteed to be able to commit its transaction because the previous prepare request laid the groundwork. If the decision was to abort, the replica rolls back the transaction.

The coordinator in 2PC

What if the coordinator crashes?

- Coordinator writes its decision to disk

- When it recovers, read decision from disk and send it to replicas (or abort if no decision was mde before crash)

- Problem: if coordinator crashes after prepare, but before broadcasting decision, other nodes do not know how it has crashed

- Replicas participating in transaction cannot commit or abort after responding “ok” to the prepare request (otherwise we risk violating atomicity)

- Algorithm is blocked until coordinator recovers

The problem with two-phase commit is that the coordinator is a single point of failure. Crashes of the coordinator can be tolerated by having the coordinator write its commit/abort decisions to stable storage, but even so, there may be transactions that have prepared but not yet committed/aborted at the time of the coordinator crash (called

in-doubt transactions). Anyin-doubttransactions must wait until the coordinator recovers to learn their fate; they cannot unilaterally decide to commit or abort, because that decision could end up being inconsistent with the coordinator and other nodes, which might violate atomicity.

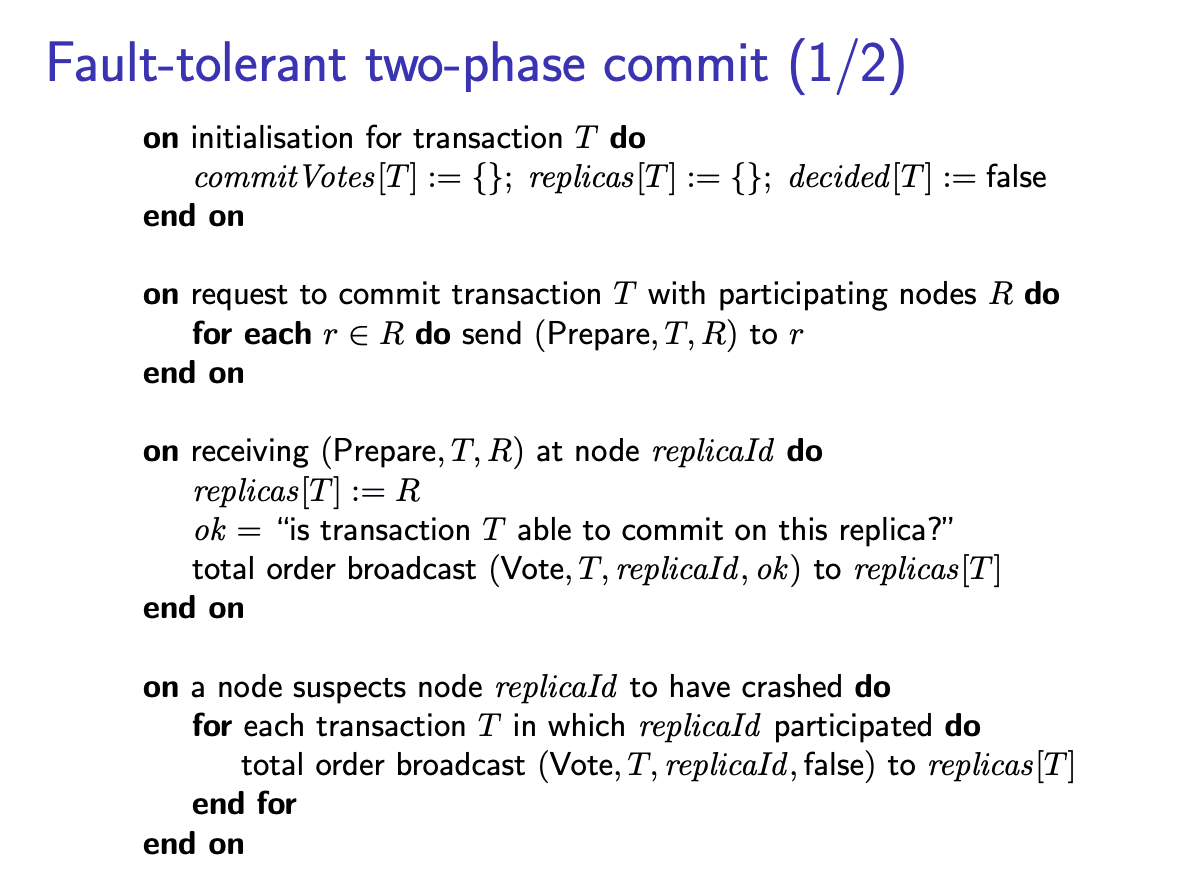

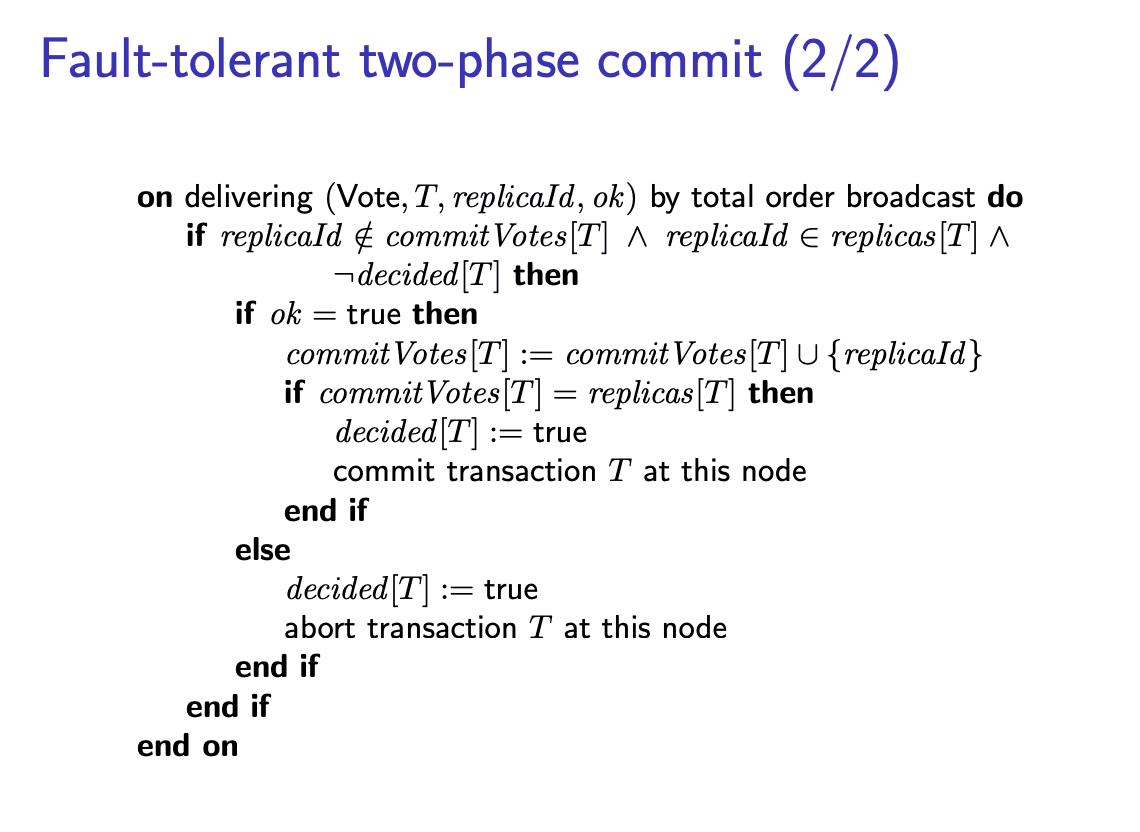

solution: Fault-tolerant 2PC:

It is possible to avoid the single point of failure of the coordinator by using a consensus algorithm or total order broadcast protocol.

Different from the previous 2PC, when one node received the “prepare” message from the coordinator, it will perform total order broadcast with message tagged with “ok” to all other replicas. And there will be a faulty detector, which can be installed on either nodes or some other servers, to suspect whether node

This introduces a race condition: if node

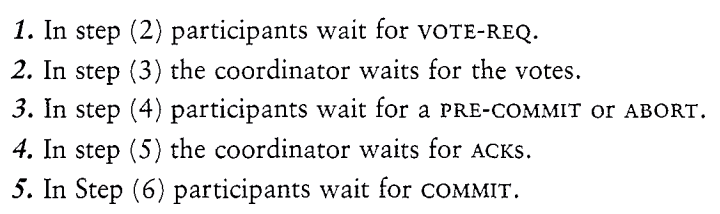

3PC

In a word, 3PC provides two mechanisms:

- Add a 1st

CanCommitstage (get the transaction lock, no log record added) to allow the use of electing recovery coordinator. - Add timeout mechanism on coordinator and node, there will be no forever waiting and retries.

Now we will elaborate why we need 3PC to solve what kinds of problems of 2PC.

In 2PC, we will encounter several kinds of failures.

First, we divide the failures into three types:

- Only slave(s) fails

- Only coordinator fails

- Coordinator and slave(s) fail together

For the 1st type of failure, we can divide it into another two possible situations:

- Slave died before sending

READYmessage back to the coordinator

The coordinator will find it does not receive the message from this slave, and it will decide to ABORT the transaction. (This means in 2PC, the coordinator kinds of have a “timeout” mechanism).

- Slave died after sending

READYmessage back to the coordinator (this means the coordinator’s decision has been made to the disk)

In 2PC, the coordinator will try forever until it get contact with the slave. And when the slave recovers, the coordinator will tell it what to do.

Actually, if the slave recovers, and find there is a

COMMITorABORTmessage in its stable log, it will perform the corresponding operations as normal recovery algorithms require.However, if it only finds a

READYrecord in its log, things get complicated. It must recontact the coordinator/wait for the coordinator’s decision to get the knowledge of the current transaction.

For the 2nd type of failure, without the help of recovery coordinator, as illustarated before in the “The coordinator in 2PC” part:

- If the coordinator doesn’t find a

COMMITorABORTrecord, just re-perform the protocol. - If the coordinator finds the

COMMITorABORTrecord, just re-perform the corresponding operation. In this process, all the slaves must wait.

Or usually, we can use a recovery coordinator to help the recovery process. It queries the participants. This process is very similar to the above.

- If at least one participant has received a

COMMITorABORTmessage then the new coordinator knows that the vote to commit must have been unanimous and it can tell the others to commit/abort. - If no participants received a

COMMITorABORTmessage then the new coordinator can restart the protocol.

But here comes the problem with the 3rd kind of failure WITH THE USE OF RECOVERY COORDINATOR.

When recover, like the discussion happend in the above part, first let we check the version WITHOUT the help of recovery coordinator:

If the coordinator doesn’t find a

COMMITorABORTrecord, just re-perform the protocol.If the coordinator finds the

COMMITorABORTrecord, just re-perform the corresponding operation. In this process, all the slaves must wait.

With the help of recovery coordinator, problems appear:

If all the live participants said they didn’t receive the COMMIT message, the coordinator does not know whether there was a consensus and the dead participant may have been the only one to receive the COMMIT message (which it will process when it recovers). As such, the coordinator cannot tell the other participants to make any progress; it must wait for the dead participant to come back. This situation is called BLOCKING.

From the above discussion, we can see that in 2PC, there are multiple cases of possible blocking, so 3PC is proposed.

Based on the discussion of the 3PC in 《Concurrency-Control-And-Recovery-in-Database-Systems》, we want to build a system with NB property:

NB: If any operational process is uncertain then no process (whether operational or failed) can have decided to commit.

This will allow uncertain process to abort since no other processes are allowed to commit. And we can consider why 2PC violates NB. The coordinator sends COMMIT to the participants while the latter are uncertain. Thus if participant COMMIT before participant q, the former will decide Commit while the latter are still uncertain, so this leads to the situation that the uncertain processes are not allowed to abort becasue some other processes might have committed themselves.

But in 3PC, we use a CanCommit period to solve this problem. After the coordinator has found that all votes were Yes, it sends PreCommit messages to the participants. When a participant

And in 3PC, we need to cope with the following timout actions:

- ABORT

- ABORT

- Elect a recovery coordinator

- Commit

- Elect a recovery coordinator

When in 3PC we encounter the above situation and we select a new recovery coordinator, then there will still be no problem since:

- If one participant is found to be in phase 2, that means that every participant has completed phase 1 and voted on the outcome. The completion of phase 1 is guaranteed. It is possible that some (died) participants may have received commit requests (phase 3). The recovery coordinator can safely resume at phase 2 (either

PREPAREorABORTbroadcasted due to theCanCommitphase). - If all participant was in phase 1, that means NO participant has started commits or aborts. The protocol can start at the beginning

- If one participant was in phase 3, the coordinator can continue in phase 3 – and make sure everyone gets the commit/abort request

There are also some problems:

The three-phase commit protocol suffers from two problems. First, a partitioned network may cause a subset of participants to elect a new coordinator and vote on a different transaction outcome. Secondly, it does not handle fail-recover well. If a coordinator that died recovers, it may read its write-ahead log and resume the protocol at what is now an obsolete state, possibly issuing conflicting directives to what already took place. The protocol does not work well with fail-recover systems.

2PC with other topology

This part is not extracted from this course, it comes from here.

We have previsouly focused on centralized 2PC.

- +None of the worker node can influence one another

- +Failure of a worker node independent

- -Put trust in coordinator

- -Hope coordinator does not fail

We try to consider other possible protocols with different latency and bandwidth.

- Time/Latency: rounds used by a protocol

- Bandwidth: messages used by a protocol

Two extremes:

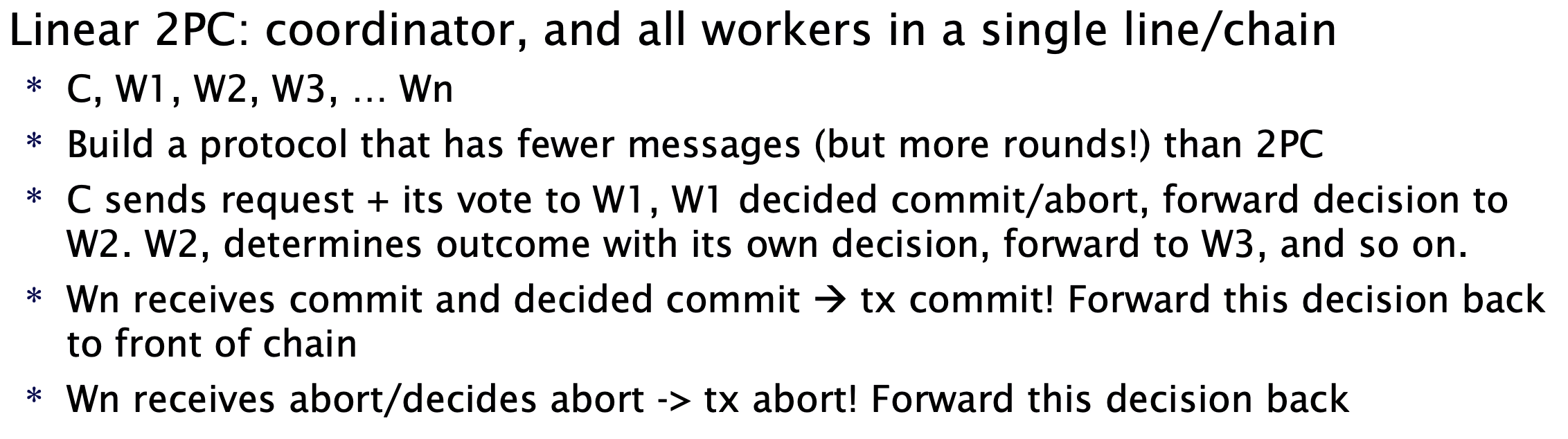

Linear 2PC: coordinator, and all workers in a single line.chain

- Build a protocol that has fewer messages (but more rounds!) than 2PC

- C-W1-W2-W3-…-Wn

Decentralized 2PC: all workers can communicate with one another

- Build a protocol that has fewer rounds (but more messages) than 2PC

The reason this method will work is: if one node tries to abort the txn, it will send message to all other nodes, and all other nodes will abort this txn all together. And all nodes will make decisions after it receives message from all other nodes, waiting otherwise.

They are still susceptible to blocking.

- Linear 2PC: Blocks if last node in the chain fails

- Decentralized 2PC: Blocks if any node fails (or msg does not arrive: not enough information)

| Messages | Rounds | |

|---|---|---|

| Centralized 2PC | 3n | 3 |

| Linear 2PC | 2n | 2n |

| Decentralized 2PC | n+n*(n-1) | 2 |

Linearizability consistency

Multiple nodes concurrently accessing reoplicated data. How do we define “consistency” here?

The strongest option: linearizability.

- Informally: every operation takes effect atomically sometime after it started and before it finished

- All operations bahave as if executed on a single copy of the data (even if there are in fact multiple replicas)

- Consequence: every operation returns an “up-to-date” value, a.k.a “strong consistency”

- Not just in distributed systems, also in shared-memory concurrency (memory on multi-core CPUs is not linearizable by default)

Note: linearizability != serializability!

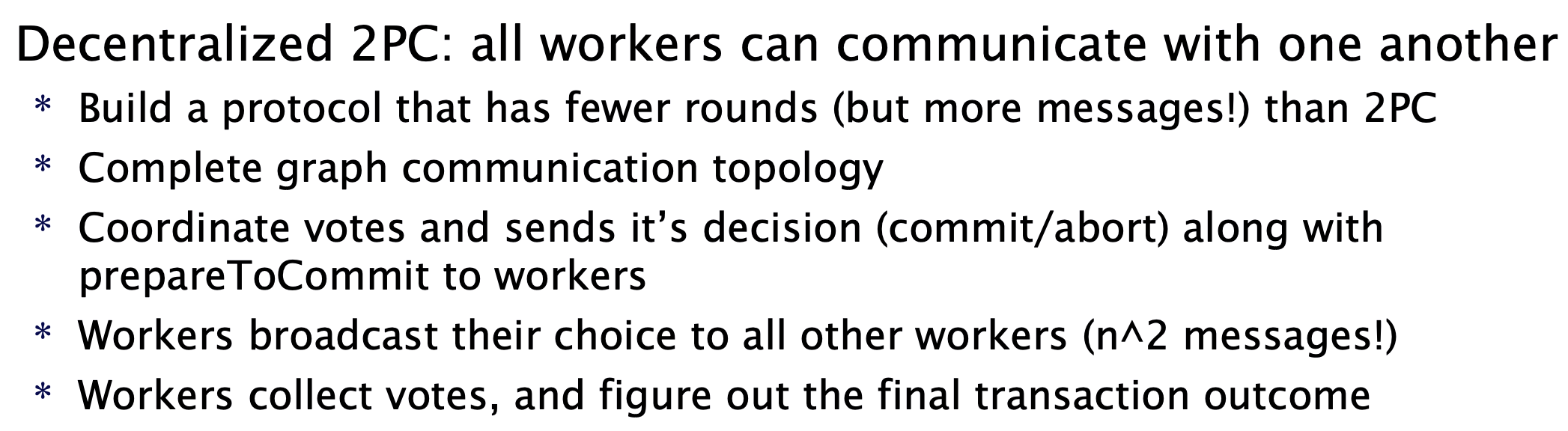

Read-after-write consistency revisited

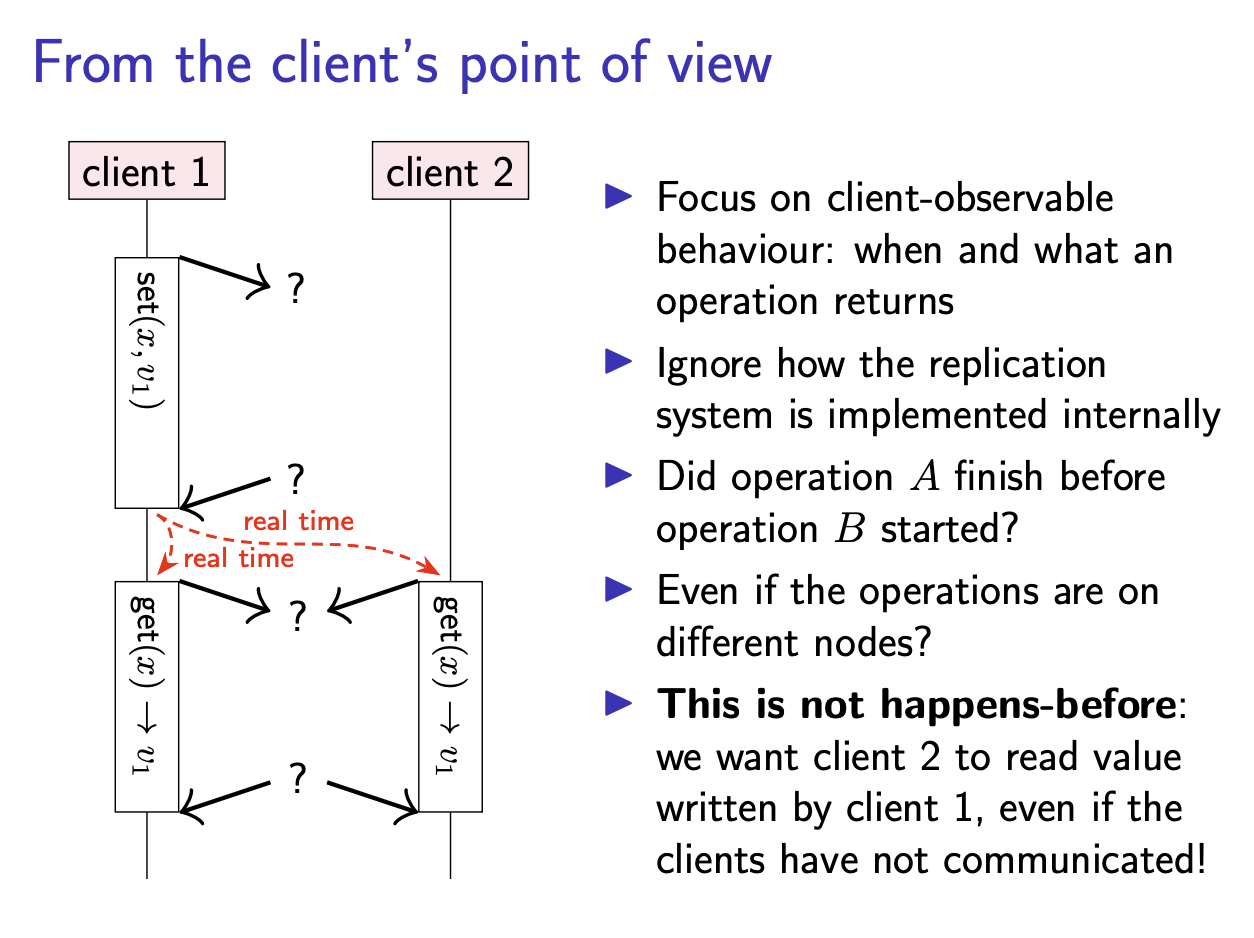

From the client’s point of view

Note: THIS IS DIFFERENT FROM HAPPENS-BEFORE.

Assume we have a global observer.

The key thing that linearizability cares about is whether one operation finished before another operation started, regardless of the nodes on which they took place. In the above figure, the two get operations both start after the set operation has finished, and therefore we expect the get operations to return the value set.

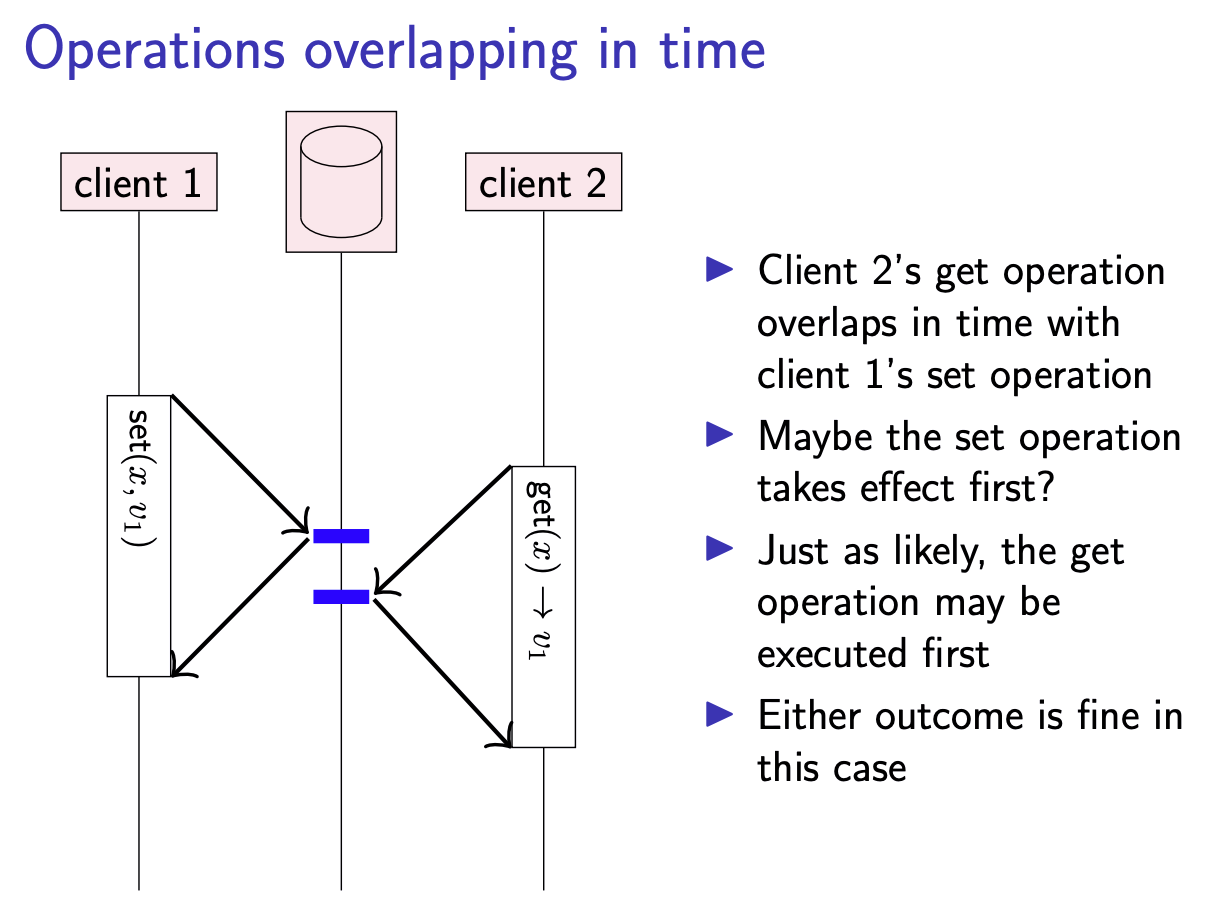

On the other hand, if the get and set operation overlap in time, in this case we don’t necessarily know in which order the operations take effect. get may return either the value set, or

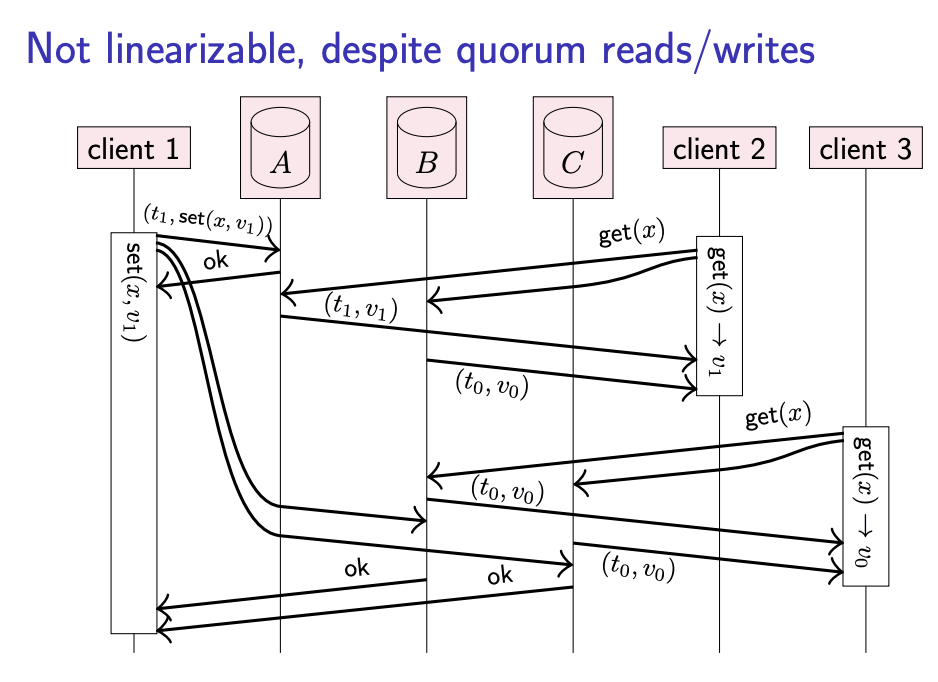

No linearizable, despite quorum reads/writes – ABD algorithm

Quorum W + Quorum R + Read Repair

Linearizability is not only about the relationship of a get operation to a prior set operation, but it can also relate one get operation to another. The above slide shows an example of a system that uses quorum reads and writes, but is nevertheless non-linearizable. Here, client 1 sets x to v1, and due to a quirk of the network the update to replica A happens quickly, while the updates to replicas B and C are delayed. Client 2 reads from a quorum of {A, B}, receives responses {v0, v1}, and determines v1 to be the newer value based on the attached timestamp. After client 2’s read has finished, client 3 starts a read from a quorum of {B, C}, receives v0 from both replicas, and returns v0 (since it is not aware of v1). Thus, client 3 observes an older value than client 2, even though the real-time order of operations would require client 3’s read to return a value that is no older than client 2’s result. This behaviour is not allowed in a linearizable system.

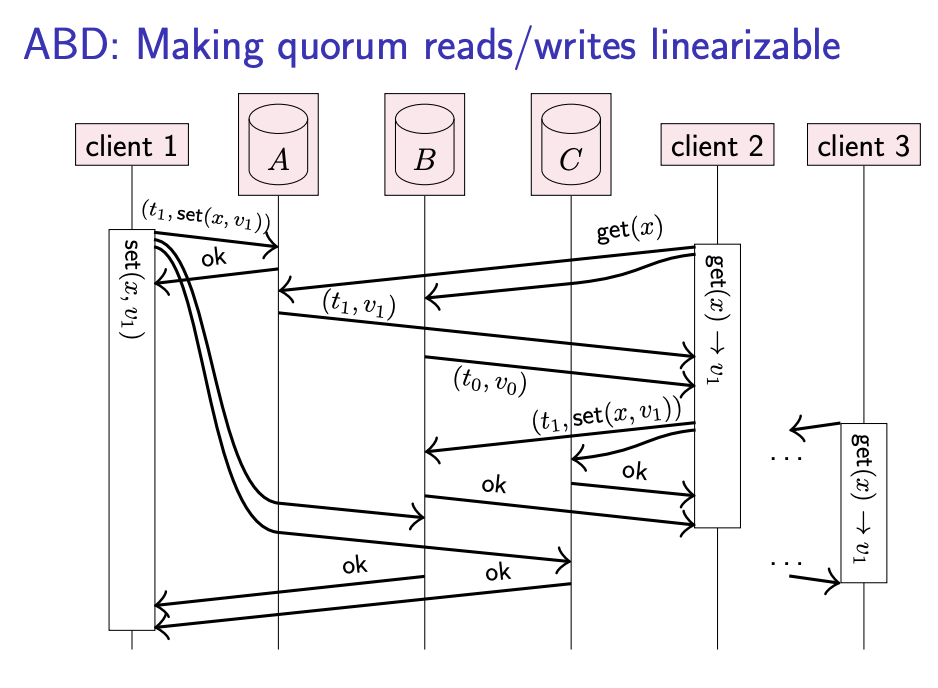

Fortunately, it is possible to make get and set operations linearizable using quorum reads and writes. First, for simplicity, assume that set operations are only performed by one designated node (we will remove this assumption later). In this model, set operations don’t change: as before, they send the update to all replicas, and wait for acknowledgement from a quorum of replicas.

For get operations, another step is required, as shown the following slide. A client must first send the get request to replicas, and wait for responses from a quorum. If some responses include a more recent value than other responses, as indicated by their timestamps, then the client must write back the most recent value to all replicas that did not already respond with the most recent value, like in read repair mentioned before. The get operation finishes only after the client is sure that the most recent value is stored on a quorum of replicas: that is, after a quorum of replicas either responded ok to the read repair, or replied with the most recent value in the first place.

The reason this method will fix the bug is that: consider a later client 3

getopertaion after client 2 has finished its op, then client 3 will read the newest result. While if client 3’sgetoperation is performed currently with client 2, then there is no extra linearizability requirement.And if all the servers read by client 2 has a old value, then the value client 3 read in this case must be as new as the one read by client 2, which will not cause a problem.

This approach is known as the ABD algorithm.

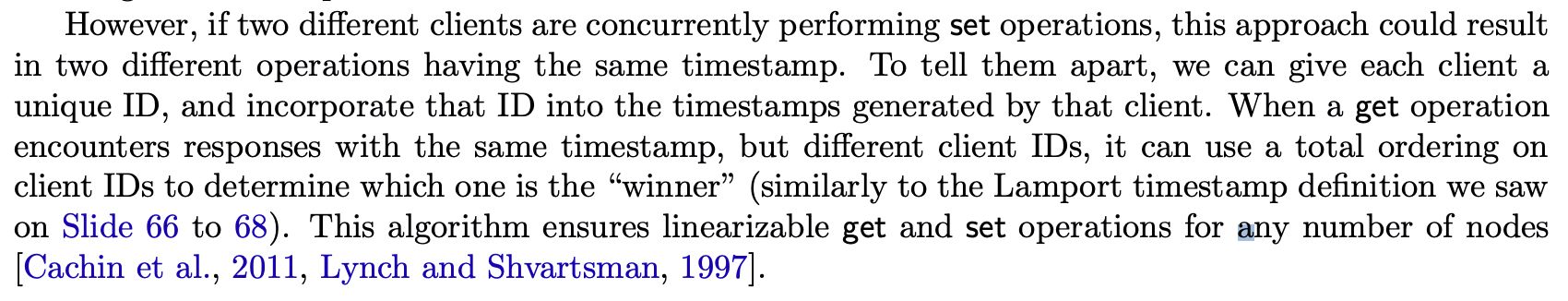

To generalize ABD algorithm to a setting where multiple nodes may perform set operations, we need to ensure timestamps reflect the real-time ordering of operations. Say operation set(x, v1) has a timestamp of set(x, v2) has a timestamp of

We can do this by having each set operation first request the latest timestamp from each replica and waiting for responses from a quorum (like in a get operation). The logical timestamp for the set operation is then one plus the maximum timestamp received from the quorum. Since the quorum is guaranteed to contain at least one replica that has observed any set operation that has completed, we get the required ordering of timestamps.

With the above optimization, we achieve three types of consistency to achieve a linearizability consistency system:

- Read-Read linearizability consistency by Read Repair

- Write-Write linearizability consistency by the above “Write Repair”

- Read-Write Consistency by quorum mechanism

Linearizability for different types of operation

This ensures linearizability of get (quorum read) and set (blind write to quorum).

- When an operation finishes, the value read/written is stored on a quorum of replicas

- Every subsequent quorum operation will see that value

- Multiple concurrent writes may overwrite each other

This is a LWW policy.

In some applications, we want to be more careful and overwrite a value only if it has not been concurrently modified by another node. This can be achieved with an atomic compare-and-swap (CAS) operation.

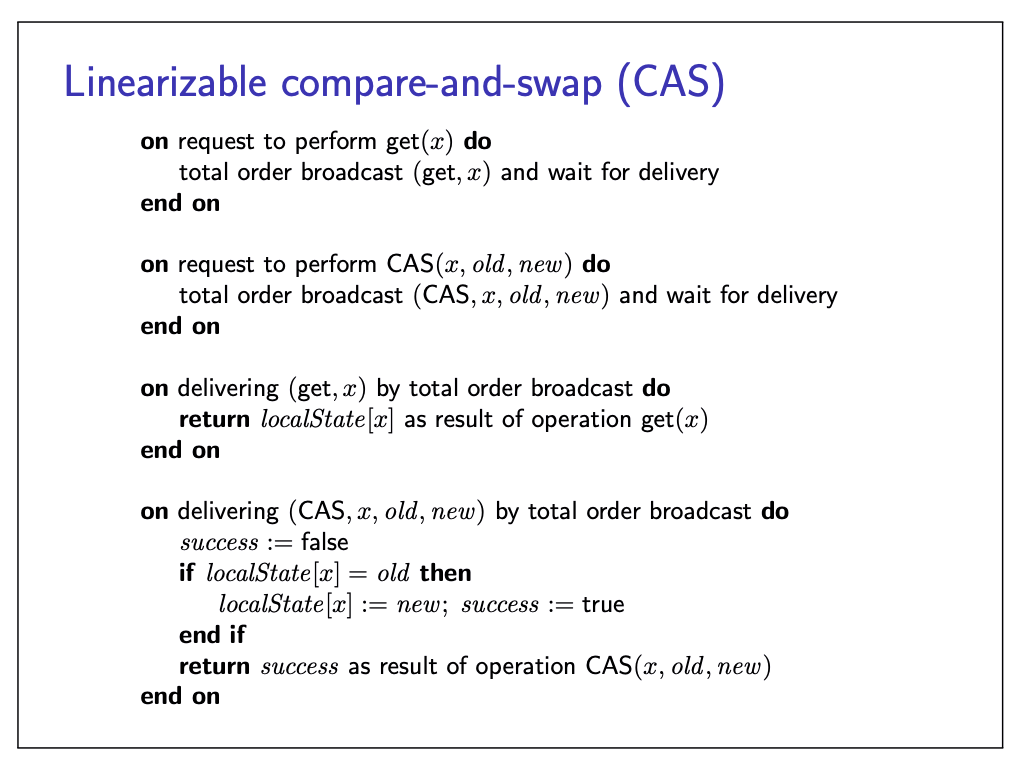

Can we implement linearizable CAS in a distributed system?

- Yes: total order broadcast to the rescue again.

Linearizable CAS

Eventual consistency

Linearizability advantages:

- makes a distributed system behave as if it were non-distributed

- Simple for applications to use

Downsides:

- Performance cost: lots of messages and waiting for repsonses

- Scalability limits: leader can be a bottleneck

- Availability problems: if you cannot contact a quorum of nodes, you cannot process any operations

That’s why we need other consistency models, such as eventual consistency.

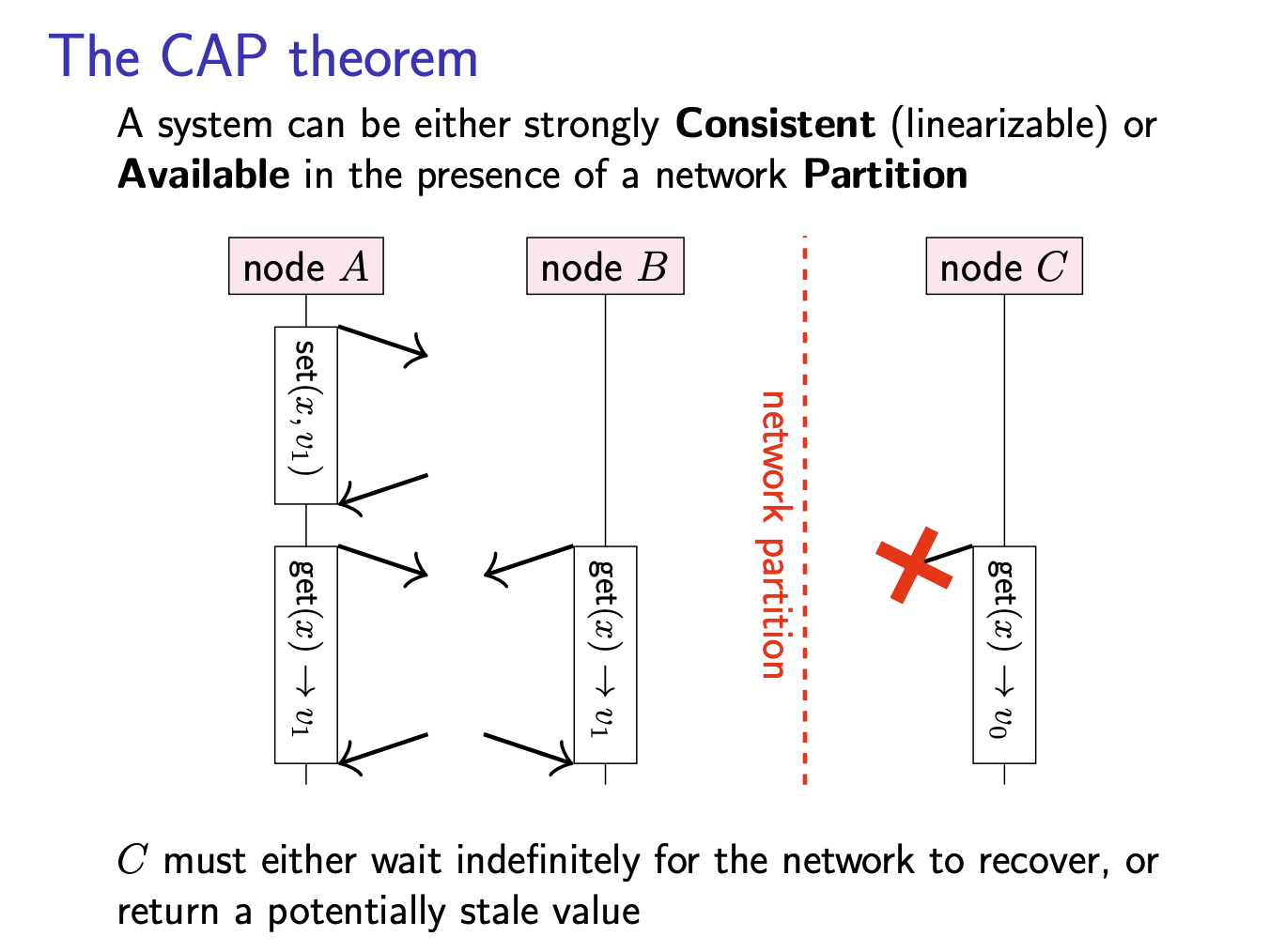

The CAP theorem

A system can be either strongly Consistent (linearizable) or Available in the presence of a network Partition.

Eventual consistency

The approach of allowing each replica to process both reads and writes based only on its local state, and without waiting for communication with other replicas, is called optimistic replication. A variety of consistency models have been proposed for optimistically replicated systems, with the best-known being eventual consistency.

Replicas process operations based only on their local state.

If there are no more replicas, eventually all replicas will be in the same state. (No guarantees how long it might take.)

Strong eventual consistency

- Eventual delivery: every update made to one non-fualty replica is eventually processed by every non-faulty replica

- Convergence: any two replicas that have processed the same set of updates are in the same state (even if updates were processed in a different order, kind of like commutative property in causal order)

Properties:

- Does not require waiting for network communication

- Causal broadcast (or weaker) can disseminate updates

- Concurrent updates

Summary of minimum system model requirements

| Problem | Must wait for communication | Requires synchrony |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic commit | all participating nodes | partially synchronous |

| Consensus, total order broadcast, linearizable CAS (these three are basically the same thing) | quorum | partcially synchronous |

| linearizable get/set | quorum | Asynchronous |

| eventual consistency, causal broadcast, FIFO broadcast | local replica only | asynchronous |

Concurrency control in applications

Nowadays we use a lot of collaboration software:

- **Examples: ** canlendar sync, Google Docs, …

- Several users / devices working on a shared file.document

- Each user device has local replica of the data

- Update local replica anytime (even while offline), sync with others when netowkr available

- **Challenge: **how to reconcile current updates?

Families of algorithms:

- Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs)

- Operation-based

- State-based

- Operational Transformation (OT)

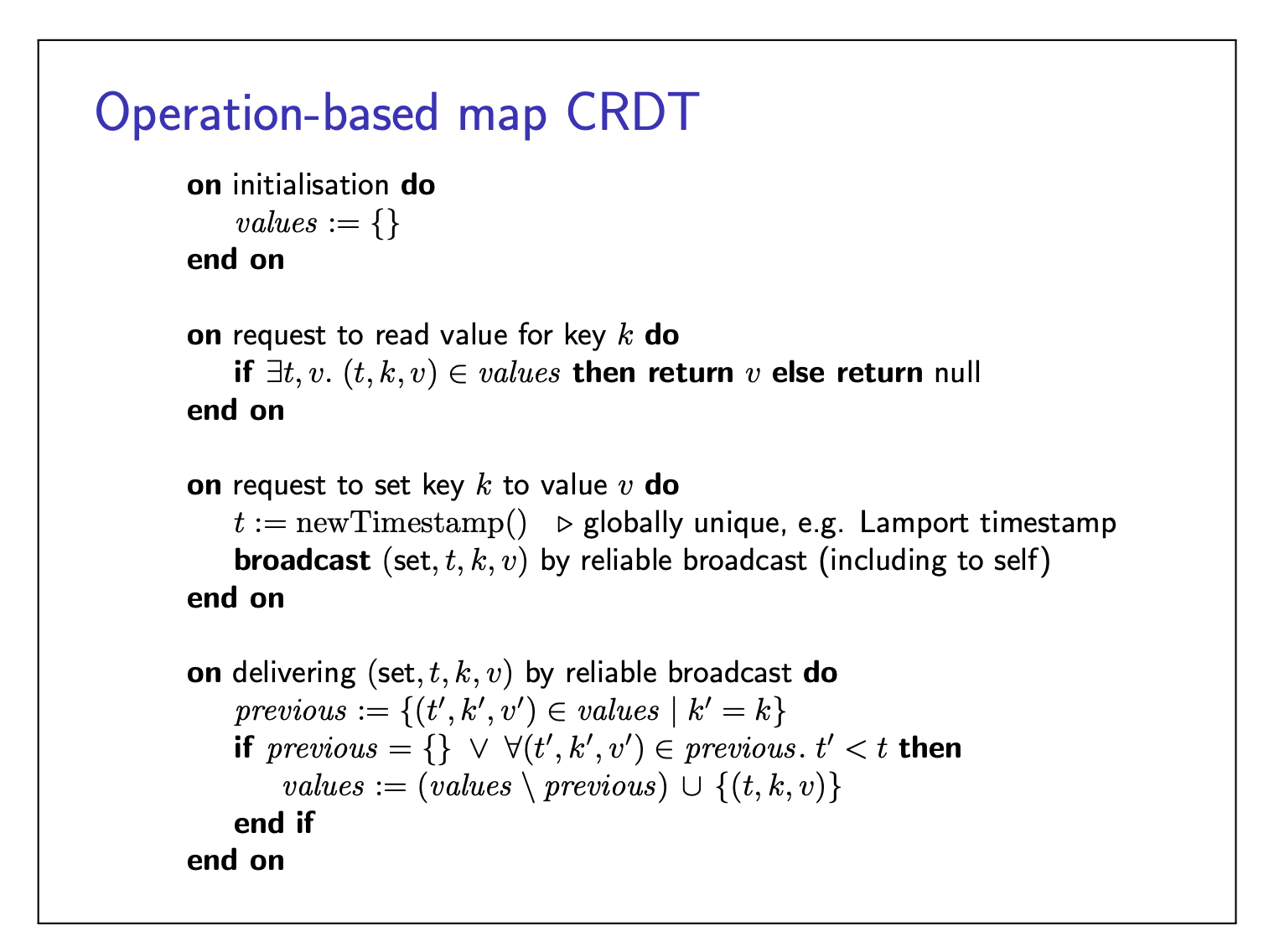

Operation-based map CRDT

It is an operation-based CRDT because each broadcast message contains a description of an update operation (as opposed to state-based CRDTs).

Reliable broadcast mat deliver updates in any order:

- Broadcast (set,

- Broadcast (set,

Recall strong eventual consistency:

- Eventual delivery: every update made to one non-faulty replica is eventually processed by non-faulty replica

- Convergence: any two replicas that have processed the same set of updates are in the same state

CRDT algorithm implements this:

- Reliable broadcast ensures every operation is eventually devliered to every (non-crashed) replica

- Applying an operation is commutative: order of delivery doesn’t matter (can use reliable broadcast, without requiring totally ordered delivery)

For the concurrent scenario, apparently it uses a LWW policy.

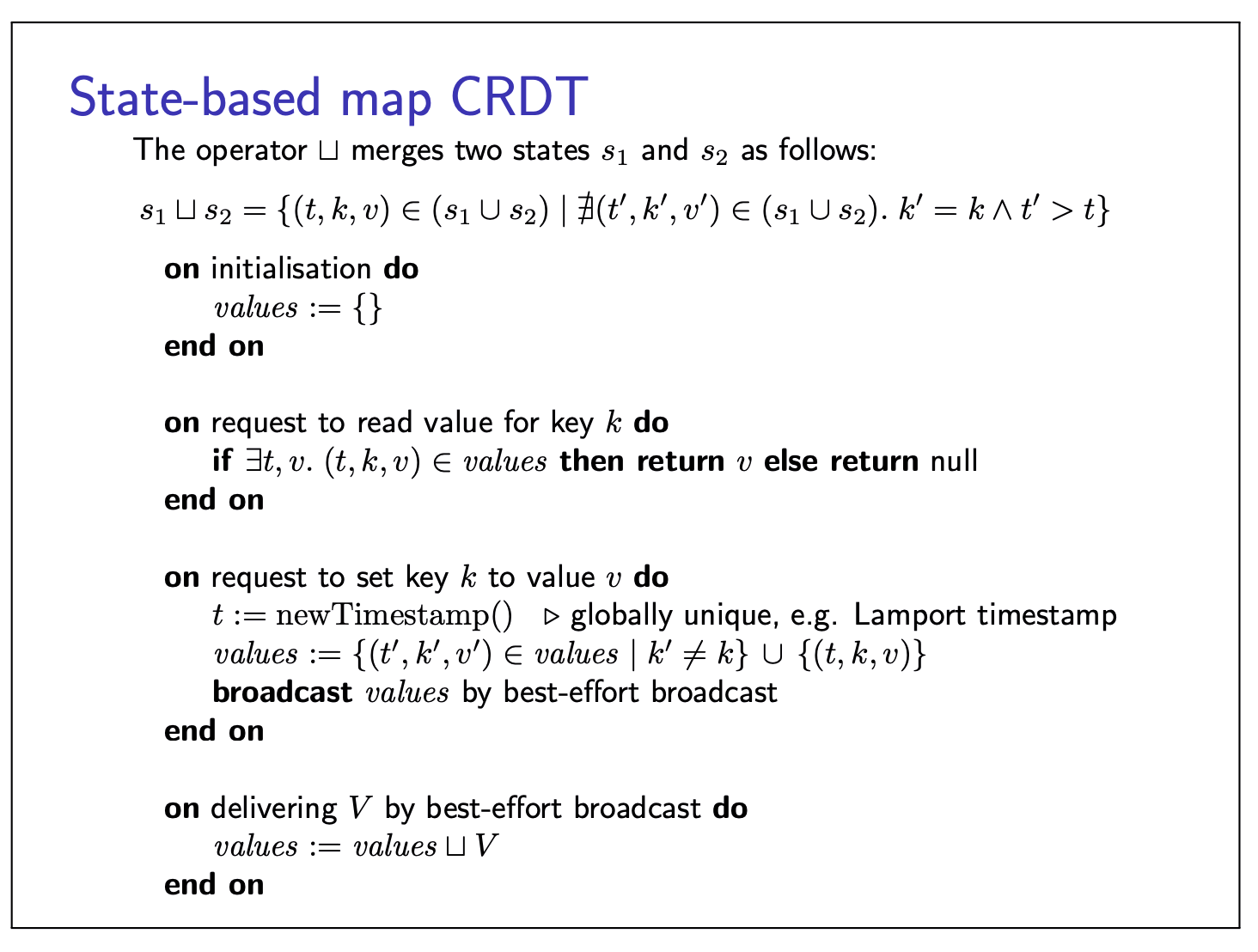

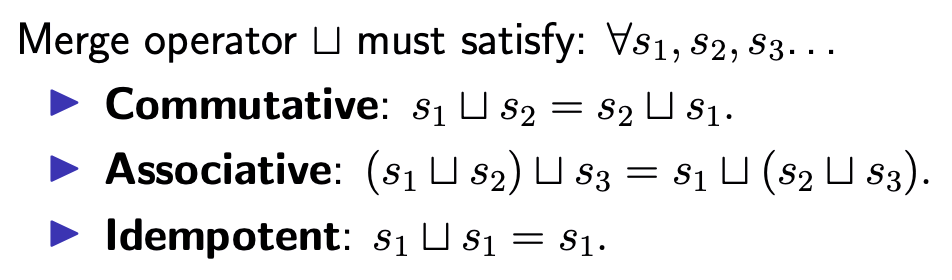

State-based map CRDT

Here, we introduces a merge operator, which only saves the latest version in the final state of each mapped k.

Note here, updates are handled differently: instead of broadcasting each operation, we directly update values and then broadcast the whole of values. On delivering this message at another replica, we merge together the two replicas’ states using a merge function. This merge function compares the timestamps of entries with the same key, and keeps those with the greater timestamp. This approach of broadcasting the entire replica state and merging it with another replica’s state is called a state-based CRDT.

State-based CRDT not necessarily uses broadcast, it can also merge concurrent updates to replicas e.g. in quorum replication, anti-entropy.

State-based -versus- operation-based:

- Op-based CRDT typically has smaller messages

- State-based CRDT can tolerate message loss/duplication ( as long as two replicas eventually succeed in exchanging their latest states, they will converge to the same state, even if some earlier messages were lost. Duplicated messages are also fine because the merge operator is idempotent. This is why a state-based CRDT can use unreliable best-effort broadcast, while an operation-based CRDT requires reliable broadcast (and some even require causal broadcast).)

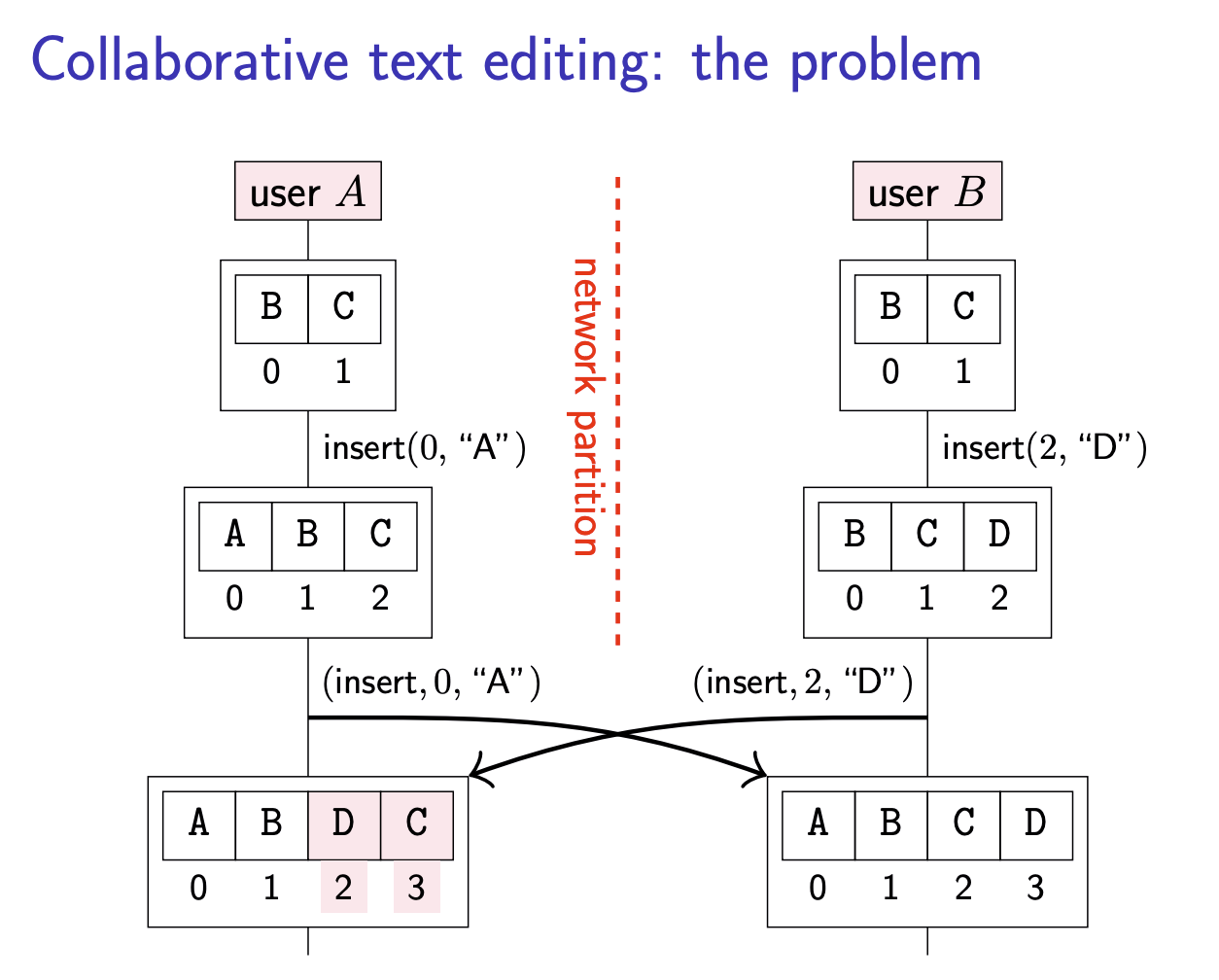

Collaborative text editing: the problem

The problem is that at the time when B performed the operation insert(2, “D”), index 2 referred to the position after character “C”. However, A’s concurrent insertion at index 0 had the effect of increasing the indexes of all subsequent characters by 1, so the position after “C” is now index 3, not index 2.

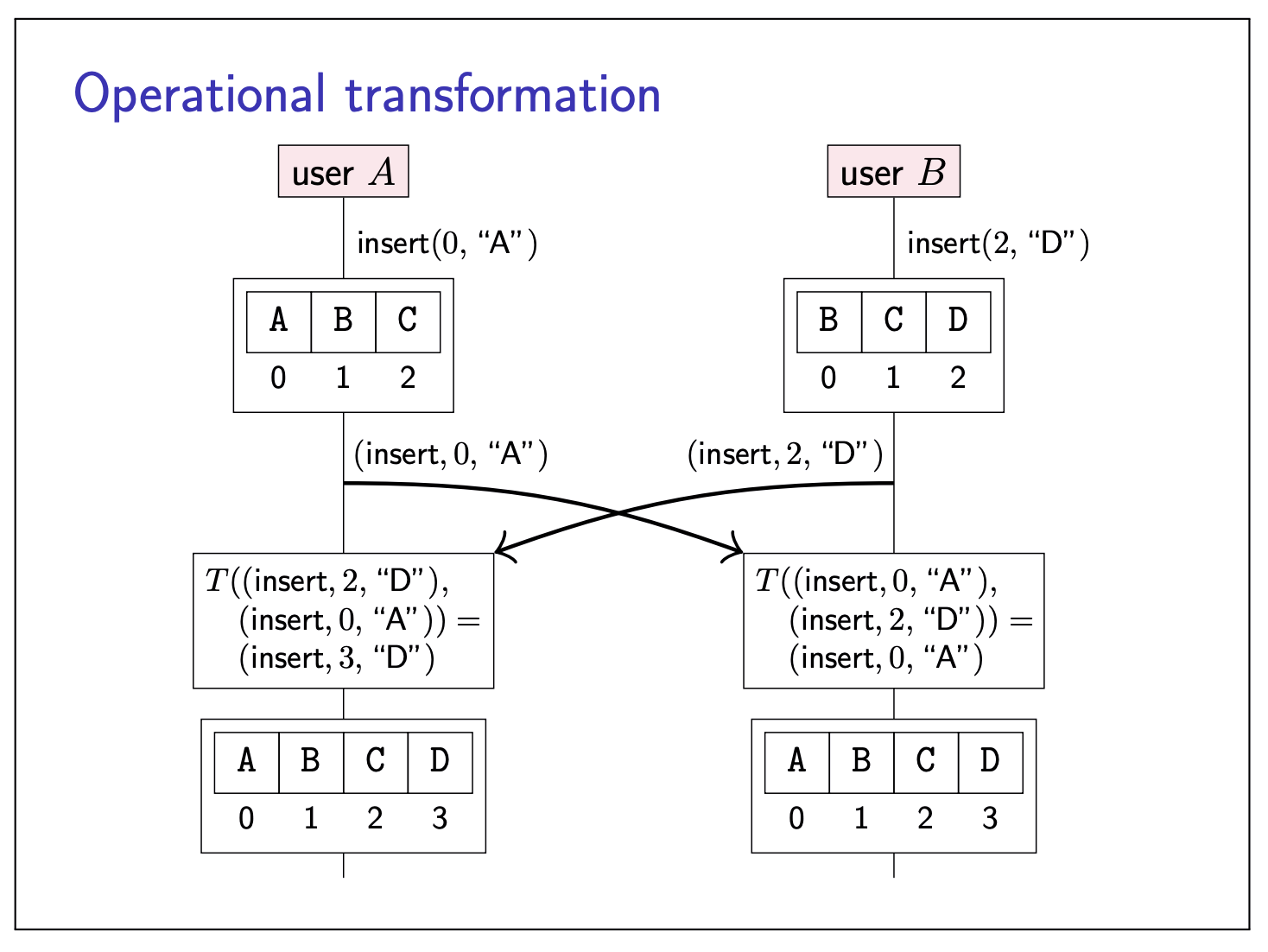

Operational transformation

Operational transformation is one of the approach to solve this problem. The general principle they have in common is:

A node keeps track of the history of operations it has performed. When a node receives another node’s operation that is concurrent to one or more of its own operations, it transforms the incoming operation relative to its own, concurrent operations.

However, the transformation function becomes more complicated when deletions, formatting etc. are taken into account. An alternative to operational transformation, which avoids the need for total order broadcast, is to use a CRDT for text editing.

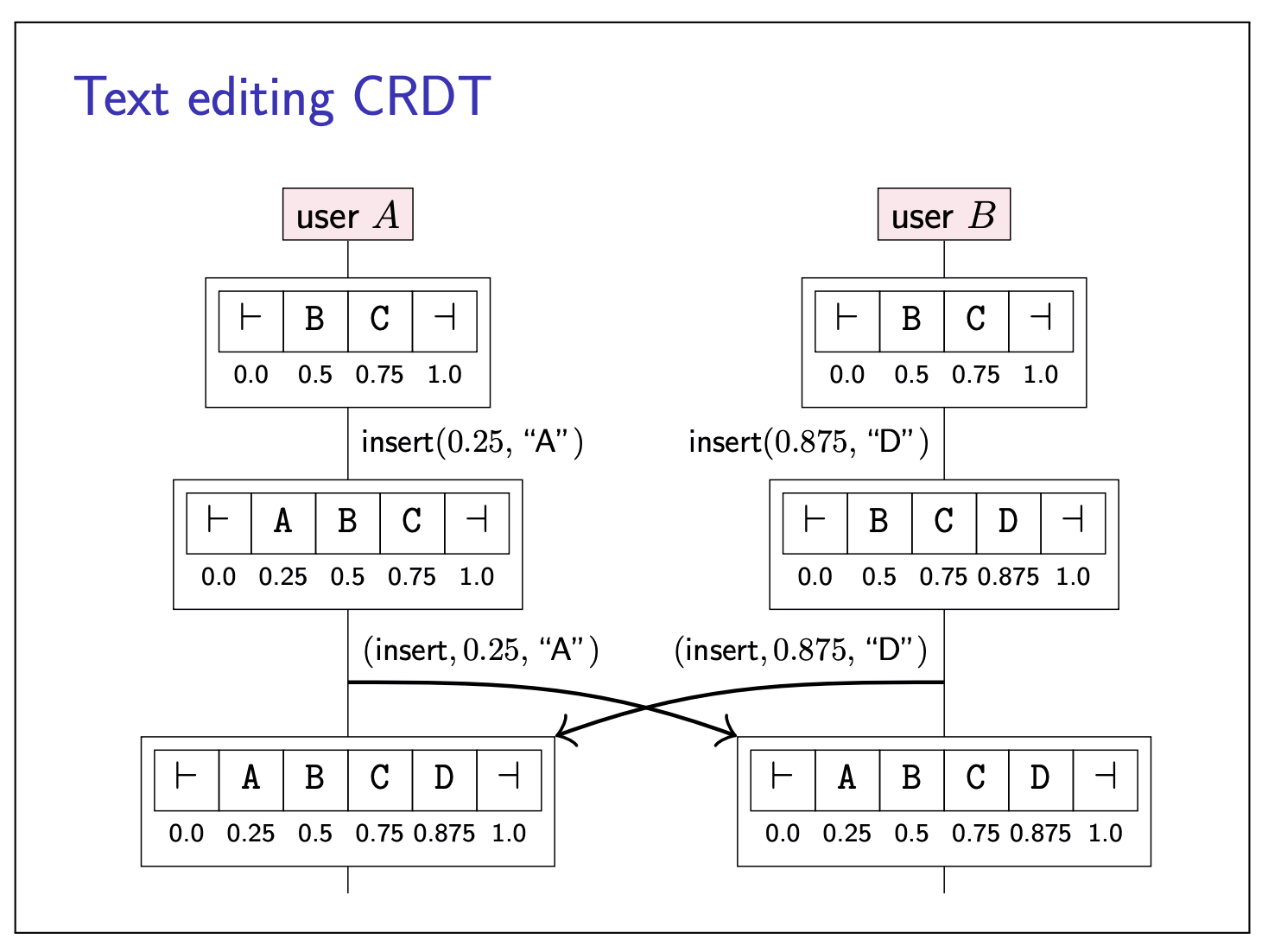

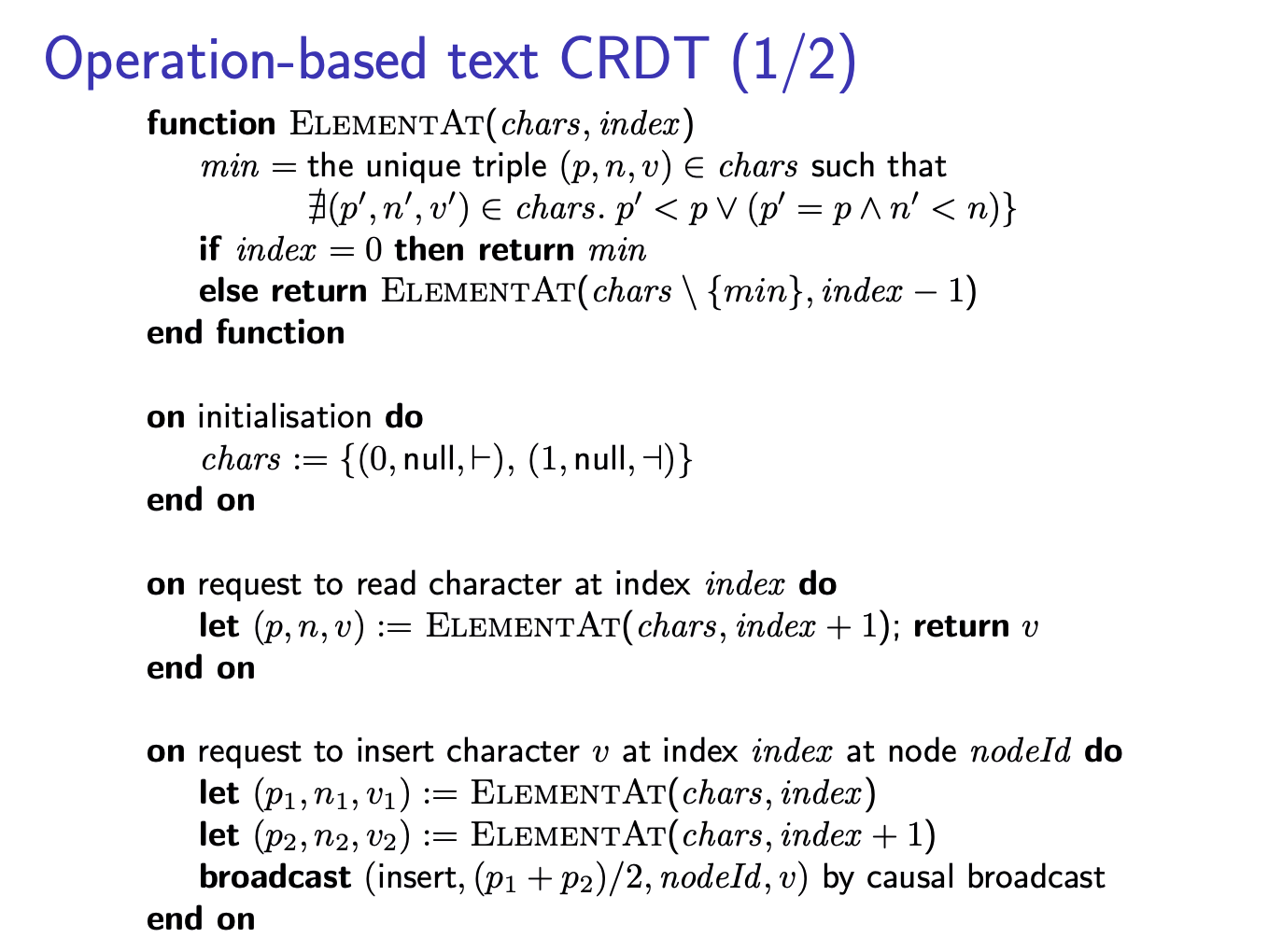

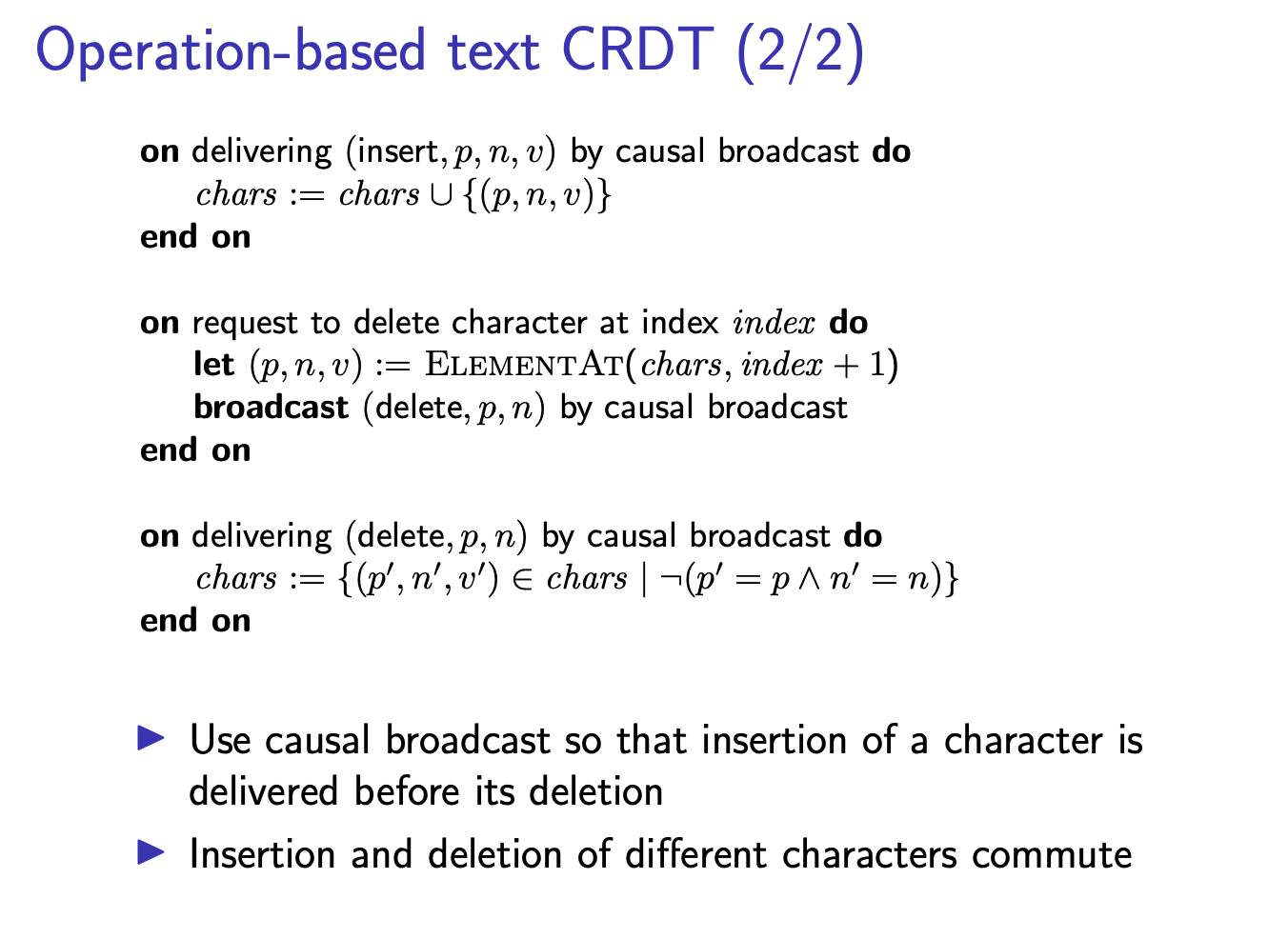

Text Editing CRDT

Rather than identifying positions in the text using indexes, and thus necessitating operational transformation, text editing CRDTs work by attaching a unique identifier to each character. These identifiers remain unchanged, even as surrounding characters are inserted or deleted.

It is possible for two different nodes to generate characters with the same position number if they concurrently insert at the same position, so we can use the ID of the node that generated a character to break ties for any characters that have the same position number. Using this approach, conflict resolution becomes easy: an insertion with a particular position number can simply be broadcast to other replicas, which then add that character to their set of characters, and sort by position number to obtain the current document.

|  |

- Use causal broadcast so that insertion of a character is delivered before its deletion.

- Insertion and deletion of different characters commute.

Google Spanner

Consistency properties:

- Serializable transaction isolation

- Linearizable read and writes

- Many shards, each holding a subset of the data; atomic commit of transactions across shards

Many standard techniques:

- State machine replication (Paxos) within a shard

- 2PL for serializability

- 2PC for cross-shard atomicity

The interesting bit: read-only transactions require no locks!

Consistent snapshot

A read-only transaction observers a consistent snapshot:

If

- Snapshot reflecting writes by

- Snapshot that does not reflect writes by

- In other words, snapshot is consistent with causality

- Even if read-only transactgion runs for a long time

Approach: MVCC

- Each read-write transaction

- Every value is tagged with timestamp

- Read-only transaction

Obtaining commit timestamps

Must ensure that whenever

- Physical clocks may be inconsistent with causality.

- Can we use Lamport clocks instead?

- Problem: linearizability depends on real-time order, and logical clocks may not reflect this!

Usually, in this case, since we have observed the “happens-before” relationship between A and B (there is also linearizability here), so the

However, the communication goes via a user, and we cannot expect a human to include a properly formed timestamp on every action they perform. Without a reliable mechanism for propagating the timestamp on every communication step, logical timestamps cannot provide the ordering guarantee we need.

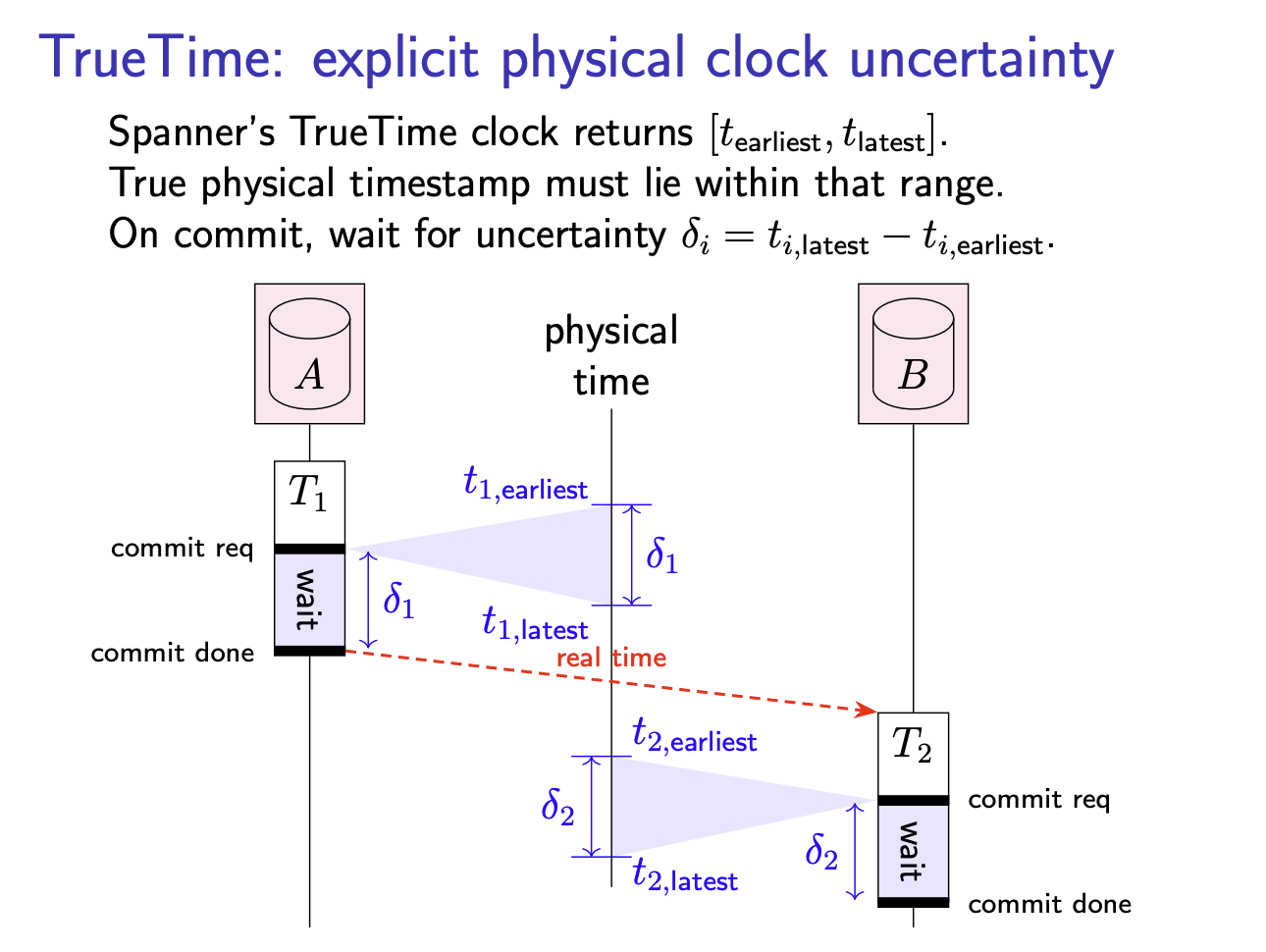

TrueTime: explicit physical clock uncertainty

Assign the

Even though we don’t have perfectly synchronised clocks, and thus a node cannot know the exact physical time of an event, this algorithm ensures that the timestamp of a transaction is less than the true physical time at the moment when the transaction commits. Therefore, if

begins later in real time than , the earliest possible timestamp that could be assigned to must be greater than ’s timestamp. Put another way, the waiting ensures that the timestamp intervals of and do not overlap, even if the transactions are executed on different nodes with no communication between the two transactions.

Since every transaction has to wait for the uncertainty interval to elapse, the challenge is now to keep that uncertainty interval as small as possible so that transactions remain fast.

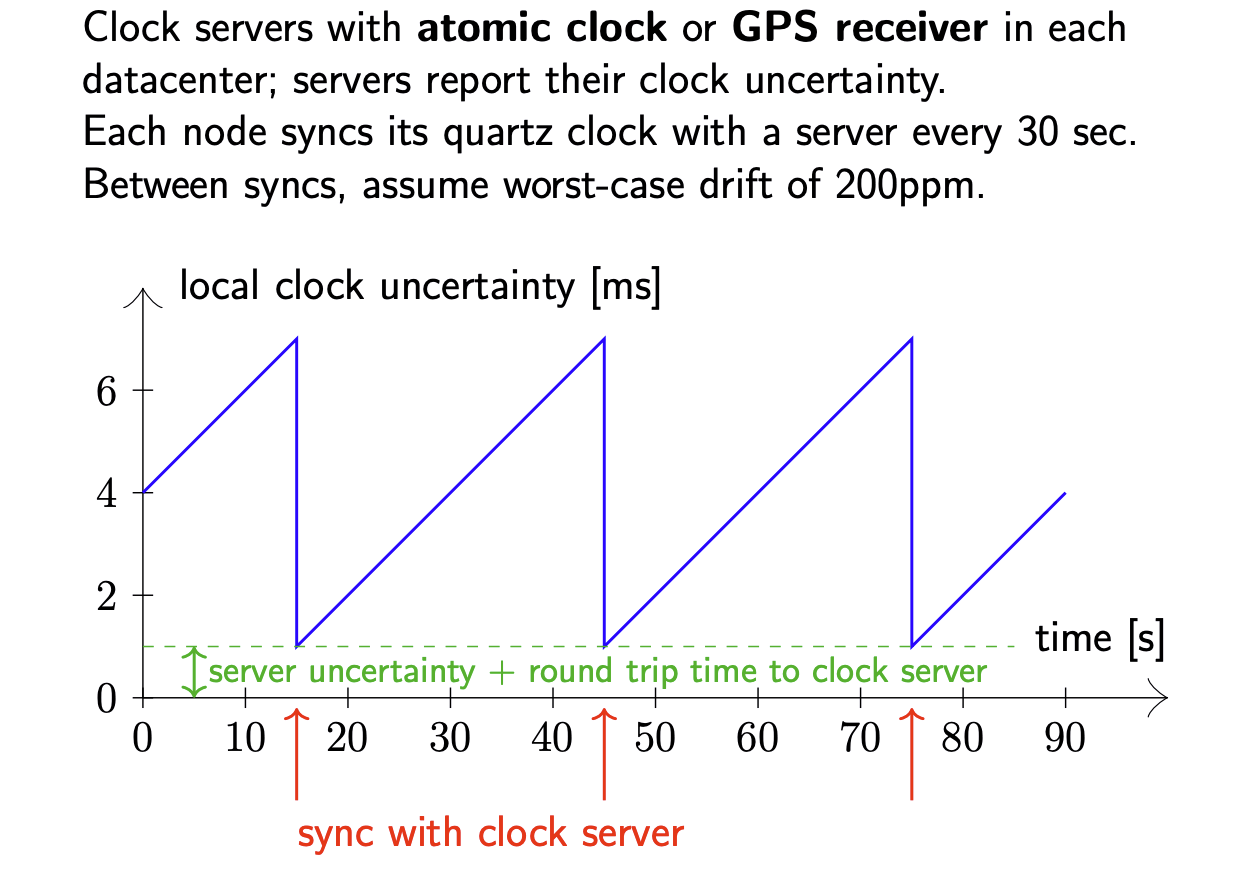

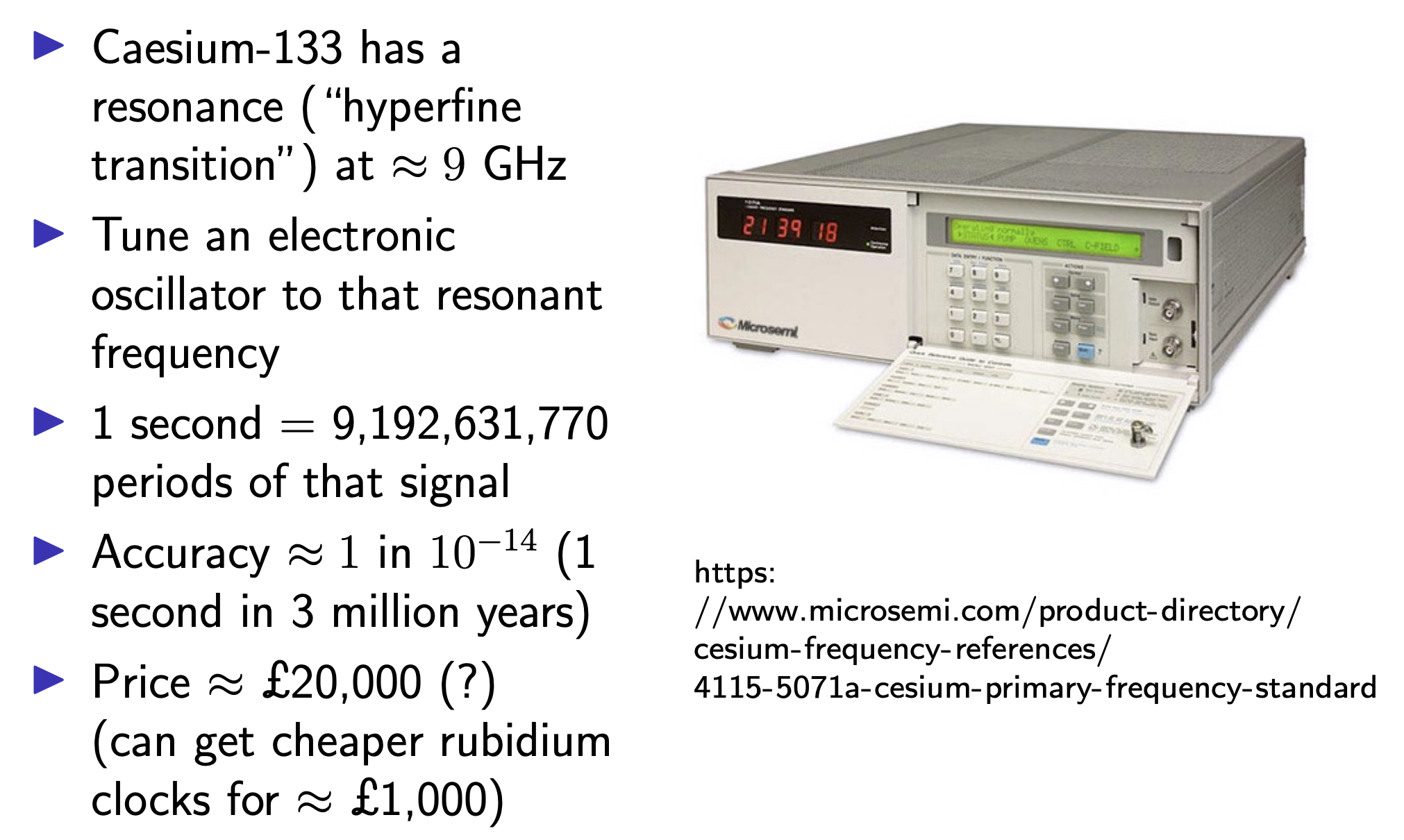

Determining clock uncertainty in TrueTime

Google achieves this by installing atomic clocks and GPS receivers in every datacenter, and synchronising every node’s quartz clock with a time server in the local datacenter every 30 seconds. In the local datacenter, round-trips are usually below 1 ms, so the clock error introduced by network latency is quite small. If the network latency increases, e.g. due to congestion, TrueTime’s uncertainty interval grows accordingly to account for the increased error.